Queen Elizabeth’s exhausting 16-hour work day

A look back at Pierre Berton’s 1953 report from behind the scenes of the royal household and the ‘strange job of being Queen’

Share

This story was first published on May 15, 1953. Read the story in the Maclean’s archives.

In 1953, a year after Queen Elizabeth II ascended the throne, Maclean’s ran a series—marking her official coronation—by acclaimed author and historian Pierre Berton, entitled The family in the palace. It’s an intimate portrait of the private and public princess turned Queen. You can read more of the series here.

IT IS seven o’clock of a dull, drizzling, terribly English morning in November and London is hardly yet awake. In Lyons Corner House, near Charing Cross, a few early risers are gulping morning coffee with their kippers but few other restaurants are open. The commuter trains are not yet disgorging their human cargoes into the streets and most of the city’s white-collar workers are still slumbering in suburban villas. But in a baroque bedchamber at the end of the Mall, a chime is sounding and one executive is already throwing back the monogrammed sheets. The Queen is preparing to meet her day.

She is sipping tea from a delicate porcelain cup brought to her by her redheaded and taciturn Scots maid, Margaret (Bobo) MacDonald, and she is listening to another MacDonald from the Scots Guards playing the pipes outside her window. By eight o’clock she is ready for the morning ritual of the BBC news, for the mail which comes in on a tray, and for the papers which are all marked for her in advance.

The Queen reads a good deal more than the marked sections. Her own photograph smiles from most of the front pages this morning for she and her sister were at a fashion show at Claridge’s the day before and almost all the papers have devoted half of a rationed page of newsprint to this event. The Telegraph reports that she showed “an intense interest” in the designs, the Mail that she “asked detailed questions as to the manufacturing and weaving” and the News Chronicle that she called the convertible skirts “a terribly good idea.”

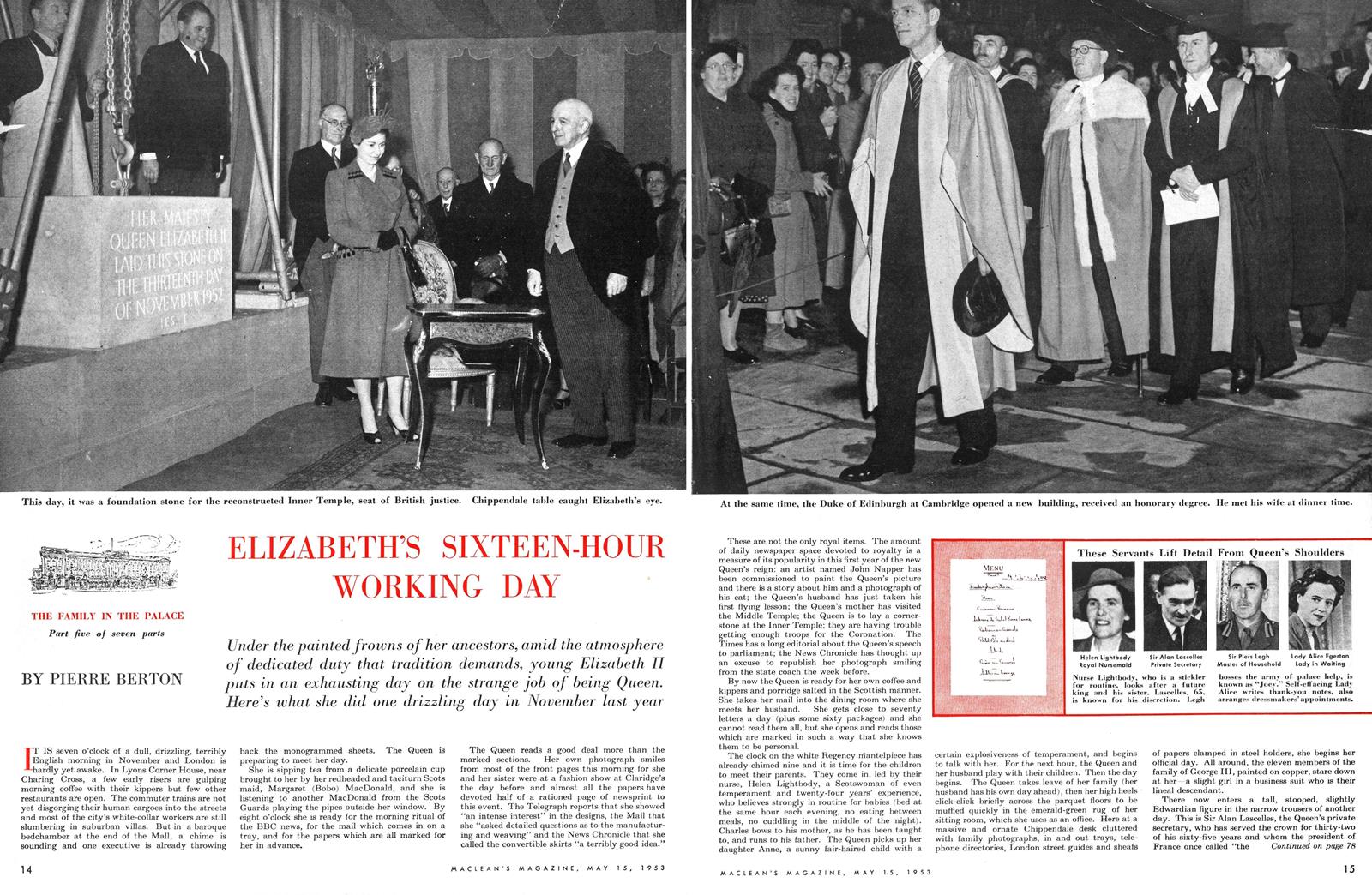

These are not the only royal items. The amount of daily newspaper space devoted to royalty is a measure of its popularity in this first year of the new Queen’s reign: an artist named John Napper has been commissioned to paint the Queen’s picture and there is a story about him and a photograph of his cat; the Queen’s husband has just taken his first flying lesson; the Queen’s mother has visited the Middle Temple; the Queen is to lay a cornerstone at the Inner Temple; they are having trouble getting enough troops for the Coronation. The Times has a long editorial about the Queen’s speech to parliament; the News Chronicle has thought up an excuse to republish her photograph smiling from the state coach the week before.

By now the Queen is ready for her own coffee and kippers and porridge salted in the Scottish manner. She takes her mail into the dining room where she meets her husband. She gets close to seventy letters a day (plus some sixty packages) and she cannot read them all, but she opens and reads those which are marked in such a way that she knows them to be personal.

The clock on the white Regency mantelpiece has already chimed nine and it is time for the children to meet their parents. They come in, led by their nurse, Helen Lightbody, a Scotswoman of even temperament and twenty-four years’ experience, who believes strongly in routine for babies (bed at the same hour each evening, no eating between meals, no cuddling in the middle of the night). Charles bows to his mother, as he has been taught to, and runs to his father. The Queen picks up her daughter Anne, a sunny fair-haired child with a certain explosiveness of temperament, and begins to talk with her. For the next hour, the Queen and her husband play with their children. Then the day begins. The Queen takes leave of her family (her husband has his own day ahead), then her high heels click-click briefly across the parquet floors to be muffled quickly in the emerald-green rug of her sitting room, which she uses as an office. Here at a massive and ornate Chippendale desk cluttered with family photographs, in and out trays, telephone directories, London street guides and sheafs of papers clamped in steel holders, she begins her official day. All around, the eleven members of the family of George III, painted on copper, stare down at her —a slight girl in a business suit who is their lineal descendant.

There now enters a tall, stooped, slightly Edwardian figure in the narrow trousers of another day. This is Sir Alan Lascelles, the Queen’s private secretary, who has served the crown for thirty-two of his sixty-five years and whom the president of France once called “the most discreet man in Europe.” For ten years no major palace decision has been made without consulting this eagle-faced courtier with the piercing brown eyes and the steel-rimmed glasses. He is a power not only within the palace but outside it, for it was he who persuaded Clement Attlee to change his mind and appoint Ernest Bevin to the Foreign Office rather than Hugh Dalton in the first days of the Labour government. Soon he will retire with a peerage as his reward but now in his quiet, deferential way he is talking to his Queen who settles back in her armchair and smiles and calls him by his nickname “Tommy.”

With Lascelles the Queen goes over her diary deciding which engagements to fill and which to reject, for she can only manage to accept about one in every fifty requests for her presence. She accepts her secretary’s advice on these matters, then signs the documents he has brought in to her. This done, they discuss the implications of the day’s news, the minutes of the last cabinet meeting, the latest dispatches from the Foreign Office.

As soon as Lascelles leaves her the duty assistant private secretary enters. There are three of them, but this morning it is Lieut.-Col. the Hon. Martin Charteris, a deceptively casual courtier whose make-up and background are so typically British upper class that he seems like something out of a Bulldog Drummond novel. Charteris is the son of a peer, the brother of a peer and is married to a peer’s daughter. His background is Eton and Sandhurst, his hobby is wildfowling. It is hard to realize that this mild, dyspeptic and sometimes absent-minded man once roamed the alleyways of Jerusalem in a tarboosh, disguised as an Arab, was torpedoed and cast adrift on a raft to be rescued at the point of death, and took part in some of the earliest and bitterest desert fighting of the war. His manners are impeccable: it is recorded that while tossing on the raft he carefully apologized to all and sundry for being sick.

Now this one-time adventurer, who may someday become as powerful as Lascelles, must deal with less adventurous matters. He has some photographs for the Queen to sign. Each regiment, air-force station and naval vessel in the realm is entitled to a signed portrait of the sovereign and since her accession the requests have been pouring in. The Queen, who signs her name fifty times a day, signs it again.

She goes over the details of some forthcoming engagements with Charteris. Will she leave by train or car? What time will she leave? Who will be there and who are they? Charteris, who has been an intelligence officer, briefs her succinctly about the background of the people she is to meet. Occasionally he has been known to secrete reminders on little slips of paper in the pocket of her dress or the edge of her handbag.

She is to lay a cornerstone at the bomb-damaged Inner Temple this afternoon. She will know the main actors in this brief and formal drama for they are members of her Privy Council, but she might like to say a few words to the Clerk of the Works who was present when her father opened another damaged portion of the temple. And she might want to say something to Sir Hubert Worthington, the architect. And she will recall that her father was treasurer of the Inner Temple. And there will be tea in the treasurer’s office afterward.

Charteris takes his leave, not backing toward the door as his predecessors did in Victoria’s day, but simply saying “thank you, ma’am” and walking out.

A few minutes later Sir Piers Legh, the Master of the Household, makes his entrance. The fabric of this man’s life is woven out of the same aristocratic fibre as the two who preceded him into this Regency drawing room with its green curtains and silk damask sofas. Like Charteris, he is the second son of a peer. The playing fields of Eton, the parade ground of the Grenadiers, the trenches of World War I and twenty-three years at court have shaped his life. He looks the part of old Etonian and retired Guards officer, bald, spruce, red-faced, toothy and correct; his mustache slightly abristle, the tiniest suggestion of a handkerchief peeping from his pocket. The Queen, like almost everybody else, calls him “Joey.”

Now this old army man is marshal of a domestic army of valets, housemaids, footmen, porters and pages. He is major domo of the largest home in the realm and he is here to discuss its problems with its mistress: a coming luncheon party, for example—Will special china be used? What wines would she prefer? Shall cars be sent to collect the guests? An old servant has reached retiring age, the cellar needs stocking, a footman has given notice. All these occupy the Guardsman and the Queen for the space of twenty minutes.

No Autographs for Hunters

These details discussed and dealt with, the Queen turns to more personal matters. She takes a few moments to call her sister who has become a little shy about such things since Elizabeth became Queen and will not call her. The two chat brightly, if briefly, and then the Queen calls in one of her acting women of the bedchamber, Lady Alice Egerton.

Lady Alice fits neatly into the jigsaw puzzle of palace heirarchy. Her sister, who was lady in waiting to the Queen when she was princess, is married to a Colville who was once secretary to the Princess and who is in turn related to another Colville whose wife is the daughter of Sir Piers Legh. Lady Alice, herself, fulfills one of the requisites of a lady in attendance on the Queen: she blends quietly with the tapestries and the woodwork. At twenty-nine she is neither quite pretty nor quite plain. She wears quiet suits in quiet colors with a quiet string of pearls, and her hair is perfectly but quietly coiffured. She presents a wholesome well-bred English appearance and her features, once remarked, are difficult to recall. On official occasions her presence is scarcely heeded.

Lady Alice and the Queen transact their business. There is a dressmaker’s appointment to be made, a sitting for a royal portrait to be arranged, a thank you note for an official bouquet to be written, some invitations to a private party to be sent out. There are letters for Lady Alice to write on the Queen’s behalf (“Her Majesty the Queen commands me to thank you . . . ”) for the Queen writes only the most personal letters herself in order to discourage autograph hunters.

Faintly now through the French windows come the familiar notes of the royal salute, blown on a bugle by the trumpeter of the Queen’s Life Guards riding at the head of twenty-two mounted troopers jogging down Constitution Hill toward Whitehall where they will mount the Long Guard, as they have done daily for three hundred years. In the nursery at the front of the palace on the top floor little Prince Charles presses his face against the pane and watches the troopers ride by in their scarlet tunics and white breeches with their shining cuirasses and breastplates and helmets.

The Queen is pausing for coffee, white without sugar. She would like a chocolate biscuit, of which she is very fond, but she has vowed to put such luxuries behind her in favor of a slimmer figure. All about her, as she sips her coffee, the great unseen hive of the palace is buzzing.

Sir John Wilson, a cheerful and burly Scot, is for the millionth time hinging new stamps in one of the volumes of the Royal Philatelic Collection. Sir Dermot Kavanagh, the crown equerry, is attending to the refurbishing of the gold coach for the Coronation. In the press office, one of the innumerable Colvilles is tactfully warding off the insistent questions of an American reporter who wants to know what the Queen eats for breakfast. Elsewhere, in offices that look more like drawing rooms, secretaries are dictating to their secretaries and servants are serving other servants. The Yeoman of the Gold Pantry and his assistants are busy polishing five tons of gold plate. The vermin man is looking for rats. The clock man is winding the palace’s three hundred clocks. Twelve men are cleaning windows. The table decker is filling all the flower vases, and in the Royal Mews two men are polishing all the brass on all the harness which is so seldom used but always on view in its glass case. And when the clocks are all wound, the plate all polished, the vases all filled, the windows all washed and the harness all shined, it will be time for it all to be done again.

Into the Mews, now, clip-clops a little single-horse brougham, used more for economy than tradition, bearing the dispatch boxes from Whitehall. The messenger takes the boxes to Lascelles who takes them to the Queen and places them on her desk. Now her day has reached the point of its greatest meaning, for in these boxes of black, red and maroon leather, embossed with the royal firms, are locked the very vitals of the monarchy. They are the vessels which transport to the palace the oceans of paper without which the Empire cannot function, and through them, twice-daily, the Queen’s fingers can reach out and lightly brush against the shifting panorama of her realm. The appointment of an Anglican bishop, judge, governor-general, poet laureate or astronomer royal cannot be effected without the ritual of these boxes. Within their steel-and-leather casing lie the bones of history: minutes of cabinet meetings, reports from governors-general, ministerial letters, ambassadorial notes, secret documents and public memoranda, programs of future events and accounts of past ones, suggestions, ideas, appeals and protests flowing into the palace in an unending stream from the Empire, the Commonwealth and the world.

The Queen, who must read everything and sign or initial most of it, attacks the red boxes first for they contain the most important and secret documents, intended only for her eyes. Attached to the box by the latch that locks it is a slip of paper four by six inches on the end of which is inscribed the words: “From the Prime Minister.” The Queen takes a solid gold cylindrical key from a chain, inserts it into the lock, opens the box and lifts the paper from the latch. She reads the documents within and signs them, blotting her signature on the black paper which is provided and which is destroyed daily to prevent any secrets escaping. She replaces the documents, turns the route slip over, fits it back into the latch and snaps the box shut. On the other side of the slip is written: “From H.M. the Queen.” She repeats this process until the boxes are done with. Soon the little brougham is jogging back to Whitehall and the business of the realm moves on.

Now it is time for her audiences, a morning ritual which is almost as rigid as the boxes. For these she walks through a little anteroom and into the Forty-Four room, named because of its occupancy in 1844 by the Emperor Nicholas of Russia. His painted face, imprisoned in its heavy gilt frame, stares down on the Queen along with those of Louis Philippe of France, and Leopold I of the Belgians, both of whom have in their day occupied these quarters. Like almost every room in the palace the Forty-Four room is a miniature museum with its cabinets of Sèvres china, its Louis XIV writing tables, its Ch’ien Lung jar of famille rose porcelain and its cream-and-gold Regency chairs upholstered in scarlet silk. Over the red-carpeted threshold and into this exquisite little showpiece of a room the tides of Empire wash daily. Sooner or later every important official of the crown will come to this or to a similar room to meet his Queen: field marshals to receive their batons, prime ministers to report on their corner of the Commonwealth, colonial governors fresh from the coconut palms of the West Indies or the blue jacarandas of Fiji, high commissioners, Foreign Office men, first sea lords, diplomats.

Today there will be four audiences of about fifteen minutes each, granted to a cross section of the realm: To the Earl of Birkenhead who as chairman of the Royal Society of Literature has come to ask the new Queen to be its patron; to the Rt. Hon. Sir Arthur Salter, Minister of State for Economic Affairs, who will discuss with her some of the economic matters contained in her speech from the throne; to Mr. Henry Studholme, MP, who, as vice-chamberlain of the household and the contact between Queen and parliament, will bring an official expression of thanks for her speech; and finally to the Rt. Hon. William Jordan, a New Zealand elder statesman who is to be knighted.

Each of these dignitaries arrives at the Privy Purse door of the palace at his appointed moment, is divested of coat, hat and umbrella by a footman in blue livery, is met by Sir Alan Lascelles and conducted by a page down the long hallways, past the white busts of former kings, the French Empire clocks, the Winterhalter paintings of Albert and Victoria, and the Carrara pillars of the Marble Hall and into the presence of the Queen. The page knocks, the Queen calls “come in,” the page announces the visitor, the visitor bows and says “Good morning, your Majesty” and the audience begins.

Here is William Joseph Jordan, a former London policeman round and florid in his morning coat, being dubbed a Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George. The Queen taps him lightly on the shoulder with the flat of a ceremonial sword, then swings it flashing in a wide arc above his head find taps him again on the other shoulder, and the accolade is conferred. Jordan is, in a sense, a symbol of the realm—a tradesman’s son from Ramsgate who left the Old Country for New Zealand and climbed slowly but stubbornly up the ladder of Labour politics until he returned to his homeland to serve as high commissioner for fifteen years. Now, under the white-and-gold ceiling and the double Corinthian pillars he is reaping his reward. A tiny clock which forms one of the eyes of a black Negress’ head on the mantelpiece ticks off the minutes while the old man, at the end of his career, talks to the young Queen on the threshold of hers. Then Bill Jordan, now Sir William, leaves his sovereign’s presence soon to slip out of his morning clothes and back into the blue single-breasted suit with the hard collar and high waistcoat that has been his uniform for a generation.

It is 12.45 and the palace is at its lunch. Down in the servants’ hall the platoons of housemaids are chattering like busy sparrows as they break their bread; in the stewards’ room, which is one step higher, the pages, footmen, yeomen and valets are eating, served by steward-room boys who some day aspire to be stewards themselves. Above stairs, the lady clerks, the Queen’s police officer, the chief accountant and their like are taking their lunch in the official mess; and in the household dining room, which is again higher up the ladder, the assistant secretaries, equerries and aides are eating in carefully graded equality. Sir Alan Lascelles is slipping into his velvet-collared coat and preparing to take his only exercise—a brisk walk down Pall Mall to the Travellers’ Club. And in the Carnarvon Room, where George VI and Churchill used to serve each other with cold buffet (for their talk was so secret that no servant must hear it), the Queen is sitting down to a simple three-course meal of fruit, meat and ice cream, in the silent painted company of Philip II of Spain, Rudolph II of Austria, Louis XIII of France and Cardinal Richelieu.

The meal done, she can rest briefly, then spend some time in the nursery with her children, Charles and Anne. The Queen walks from her suite on the ground floor of the palace down the red-carpeted hall to the ornate wrought-iron bird cage of an elevator which will take her to the top floor.

Down another red-carpeted hall she goes, past the endless variety of palace bric-à-brac which fills every space and cranny; the marble-topped tables and Chinese vases, the lutes tucked away in alcoves, the busts of former servants, the paintings of royal race horses and ancient naval battles—everything that has ever been presented to or collected by royalty, all of it sifted and catalogued and carefully arranged by Queen Mary, whose whole career seems to take on, in retrospect, some of the qualities of a filing system.

The painted race horses give way, at the corridor’s end, to real hobby horses and to other toys lining the hallway: a scale-model Austin with pedals, and a baby princess’ pram. In the old days, when the Queen was a little girl, thirty wooden horses each a foot high on wheels stood outside this doorway for she preferred them to dolls. Being as neat and meticulous by nature as her grandmother was, she let no day go by without polishing and shining each toy bridle and saddle to perfection. George VI always remarked that this love of horses was a family idiosyncrasy and Prince Charles seems to have inherited it along with a love for the army. But he is less concerned today with horses or drums than he is with the events of the morrow when he will be four years old. The discussion and play, with Miss Helen Lightbody, the imperturbable nurse, looking on, centres mainly around this topic, and Charles, who is a lively little boy, shows his excitement by tearing around the nursery and hiding in the closets pursued frantically by his small Corgi, Sugar.

The play ends; the work begins again. The Queen returns to her suite on the ground floor, which is the Belgian suite, named after her ancestor Leopold of Belgium who first stayed in it. She is occupying it temporarily until her mother and sister move out of the Royal Apartments and into Clarence House. And here, where most of the crowned heads of Europe have rested, she changes into an afternoon frock and dons a holly-red coat trimmed with black, a red matching off-the-face hat with a half veil, a pair of black gloves and black “peep-toe” shoes, which, though they have gone somewhat out of fashion, she still clings to.

Now, with Lady Alice, she walks a few yards down the corridor to the Garden Entrance which royalty always uses. There is a servant on duty here, dwarfed by the great suits of Indian armor and the elephants’ tusks hanging on the dark green walls, and the great perfume burners guarding the doorway. He is wearing the palace uniform of smooth blue battledress with gold monogram and buttons, designed by George VI to save palace laundry bills. He earns a little less than twenty dollars a week but he gets his board and keep at the palace and a pension when he retires. At the moment he is surreptitiously chewing tea leaves, for he has been across to the Bag O’ Nails for a pint of bitter and this is the accepted palace method of cleansing the breath. The palace resists change, and chlorophyll has yet to invade its precincts.

The red-and-maroon Daimler is waiting, with Chivers, the tall and impassive chauffeur, who has a boy fighting in Korea, at the wheel. The detective inspector who guards the Queen leaps out and opens the car door for her. His associates at Scotland Yard joke about this and call him “the footman inspector” but he will have the last laugh when his palace days are done and he gets his MVO and superintendentship.

The Daimler moves away with the lady in waiting on the jump seat, and the Queen a single lone figure in the back. The car moves across the red gravel forecourt and out through the wrought-iron gates. The crowd that always seems to be here sends up a cheer which the Queen acknowledges with a smile and a slight upright motion of her gloved hand in which she is clutching a tiny folded handkerchief.

The car, with its gilt radiator mascot of Britannia, moves like a shiny flat beetle down the broad avenue of the Mall where the seats for the Queen’s coronation seven months hence are already going up in skeleton form, slowly denuding the nation of every last scrap of tubular scaffolding. It crosses the busy hub of Trafalgar Square, then, by way of Northumberland Avenue, proceeds down the Westminster Embankment to the Temple, seat of British justice. It was here on May 10, 1941, that both Temple and House of Commons were damaged by bombs and since then, the Inner Temple has lain a mass of rubble scarring the heart of the old city. Now it is to be rebuilt and the stiff little ceremony that follows is as necessary to that rebuilding as bricks and mortar.

The Daimler moves into the Temple Gardens and stops alongside the excavation that marks the site of the bombed building. The Queen alights, walks up a terrace of five steps to a carpet of dark-red matting protected by a blue-and-white striped canvas marquee. Here she is greeted by the youngest of a group of sage and venerable jurists, the Rt. Hon. Lord Justice Singleton, aged sixty-eight, the Treasurer of Inner Temple. He leads her down the red pathway to a larger marquee where the others are presented to her: the Rt. Hon. Gavin Turnbull, Lord Simonds, Lord High Chancellor of England, aged seventy-one; the Rt. Hon. Rayner, Lord Goddard, Lord Chief Justice of England, aged seventy-six; and the Rt. Hon. John Allsebrook, Lord Simon, the Senior Bencher, aged eighty. They hover around the tiny bright-coated Queen like lean black hawks these tall old men, bowed over by the twin burdens of age and wisdom; Singleton who was in parliament in her grandfather’s day and Simon who was in parliament in her great-grandfather’s day and Goddard and Simonds whose memory, like the others, goes clearly back to Victoria’s Jubilee.

At the end of the marquee there stands a piece of furniture which seems as curiously out of place among all the brick and rubble of the excavation as the old men in their wing collars and cut-away coats. It is a Chippendale table and here the Queen takes her seat and picks up the quill pen in her gloved hand and signs the visitor’s book. This done, two more ancient figures are presented to her: Sir Hubert Worthington, the architect of the new building, who is sixty-six, and Sir Guy Lawrence, the head of the contracting firm who is seventy-seven. The Queen remarks that the series of brick foundations for the new structure seem very like the foundations which remain of the old one, and the old men nod and agree that this is so. For the Temple, like the monarchy, must endure as before and it is possible that these men, whose careers are the link between two Temples and two Queens, are privately remarking that this new Queen has some of the foundation qualities of her predecessor.

There are some other dignitaries to meet the Queen. She does not forget to speak to the Clerk of the Works who was present, she recalls, when her father presided at a similar function. Then she proceeds to lay the eighteen-hundred-pound stone with its inscription marking the event. She dabs the corner with a trowel full of mortar, taps it twice with a mallet and her work is done. Mallet and trowel will be carefully preserved at the Inns of Court as relics of this day.

The crowd which has gathered for the ceremony, and the workmen on the roofs of neighboring buildings, set up a cheer as the stone is lowered into place.

The Queen walks back across the grounds with the old men behind her to the treasurer’s chambers for tea and, as she goes, she waves and smiles at the crowd. Somewhere in the background is Lady Alice Egerton, as inconspicuous as ever. Tea takes less than half an hour. The Queen eats a piece of brown bread and butter and a slice of plain cake and remarks how pleased her father was to serve as treasurer of Inner Temple. Then, as the band of the Irish Guards plays a march, she steps into the Daimler which threads its way back along the Embankment and the Mall through crowds of her subjects seeking their own respite in afternoon tea. The inevitable crowd is waiting at the palace to cheer and wave and be waved back at in return. It will always be there whenever she comes and goes, and it will be there, watching and waiting, on the day she dies.

Within the great grey palace she picks up once more the loose threads of her business day. There is some private correspondence to attend to and the next day’s menus to choose. They come up handwritten in French from the chef, a burly round-faced Yorkshireman named Ronald Aubrey who came to the palace fourteen years ago from the Savoy. She makes few changes in Aubrey’s menu, for he knows her tastes. She pauses over the evening papers, and again there is news of personal interest. The Evening News says that it has learned that the Coronation will be televised and all the papers announce special feature articles coming up the next day about Prince Charles.

For another hour the Queen reverts to her role as mother. Miss Lightbody brings the children down to her and they play together. While this is going on, Mr. Henry Studholme, MP, in his office in the House of Commons, is doing his duty by his Queen. As vice-chamberlain it is his daily task to prepare “the telegram” — a written report of the day’s session of parliament. Mr. Studholme is a country gentleman by profession and a member of parliament (Cons., Tavistock, Devon) by choice. Like almost everyone connected with the palace he looks the part to an uncanny degree—a reed-thin aristocratic figure with an aquiline face and a clipped mustache of iron grey. His report runs to about four hundred words and he writes it carefully in longhand, making it, as he says, “respectful but readable” and trying his best to be “a faithful mirror reflecting the atmosphere and highlights of the day.”

Her playtime ended, the Queen learns something of the atmosphere of the afternoon in Mr. Studholme’s respectful but readable prose: there has been a question about hotel prices during the Coronation and Mr. Peter Thorneycraft, president of the Board of Trade, has replied that the Coronation Committee would investigate any overcharging. Later on Mr. Churchill had provoked laughter with a wisecrack and the Queen laughs with him. But she will not be satisfied with the four hundred words of the telegram, which is really only telegraphed when she is out of London. She will read all of Hansard before her day is through.

It is time to dress for dinner. Two thousand electric lights have been switched on and an army of fifty housemaids has suddenly appeared to draw all the curtains. The Queen bathes and selects a semiformal gown from two laid out by Bobo MacDonald who hovers in attendance over her. This discreet Scotswoman is as close to the Queen as any subject can be, so close indeed that she sometimes talks of herself and the Queen as if they were a single person. “We got engaged,” she told a friend when the Queen’s betrothal was announced.

The Duke of Edinburgh, back from an official visit to Cambridge, comes into the sitting room in his dinner jacket and the two go up to the nursery to watch Charles and Anne put to bed. The Queen reads the children a story and helps with prayers, then she and her husband return to their quarters for a pre-dinner drink, Tio Pepe sherry for Elizabeth, pink gin for Philip. Together they listen to the BBC news which reports what they already know: that the Duke has been to Cambridge to receive an honorary LL.D. after opening a new wing of the engineering laboratories and that the Queen has driven to the Inner Temple to lay a cornerstone.

Dinner is sharp at eight-thirty. The two sit down alone at a polished mahogany table without a cloth, lit by candles in ornate silver sticks. The meal is served by pages who, at Philip’s suggestion, wear white gloves, Royal Navy style. In the background the Palace Steward, head of the servants, glides silently about. Dinner consists of consomée brunoise, supreme de turbot bonne femme, perdreau en casserole, salade, crème au caramel and sablés au fromage. After he is finished Philip orders up some nuts which he cracks between his teeth, as he once did in the navy.

The Queen’s work is not yet done. The inevitable boxes are waiting again on her desk and she must attend to them at once. Then there are more documents to sign, Hansard to read, some magazines she should look at (most of them contain her picture) and some business to discuss regarding the royal racing stud. For she is the keenest royal racing enthusiast since Edward VII and hopes someday to win a Derby, as he did on two occasions.

The last hour of her day has come and in this brief time left to her the Queen relaxes. There is a canasta game with her husband, mother and sister. The Duke sips a Scotch and soda, the Queen a liqueur. Both of them are looking forward to the week end, which is one day distant, when they can flee the city for Royal Lodge, where there are no servants in livery, where the furniture is chewed by pet dogs, and where, except for the inevitable boxes, one’s time is one’s own. They have not been to Royal Lodge for a fortnight because last week end was Remembrance week end, and their presence was required in London.

As the canasta game draws to its end, the palace and the city begin to run down slowly like an unwound clock. The theatres in Leicester Square vomit out their crowds and the crowds disperse. The restaurants close their doors and the buses slow their schedule. At the end of the Mall, the palace with its six hundred-odd rooms, its ten thousand pieces of furniture, its six million dollars’ worth of gold plate and its mile of corridors grows slowly dark as one by one the lights wink out. The crowd in front of the black-and-gold railings has finally gone. Now the only movement is the sentry mechanically walking his beat and the three lions passant gardant rippling in the cold night breeze above the dark bulk of the Queen’s home. The long day is done and the Queen and her household are asleep.