The Strange fiction of Hadrian’s wall

Colby Cosh on why nations don’t really exist – and why they continue to persist

CARTER BAR, SCOTLAND – SEPTEMBER 14: (EDITORS NOTE: Image has been processed with digital filters) A Scottish Saltire flag flies on the border with England on September 14, 2014 in Carter Bar, Scotland. The latest polls in Scotland’s independence referendum put the No campaign back in the lead, the first time they have gained ground on the Yes campaign since the start of August. (Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

Share

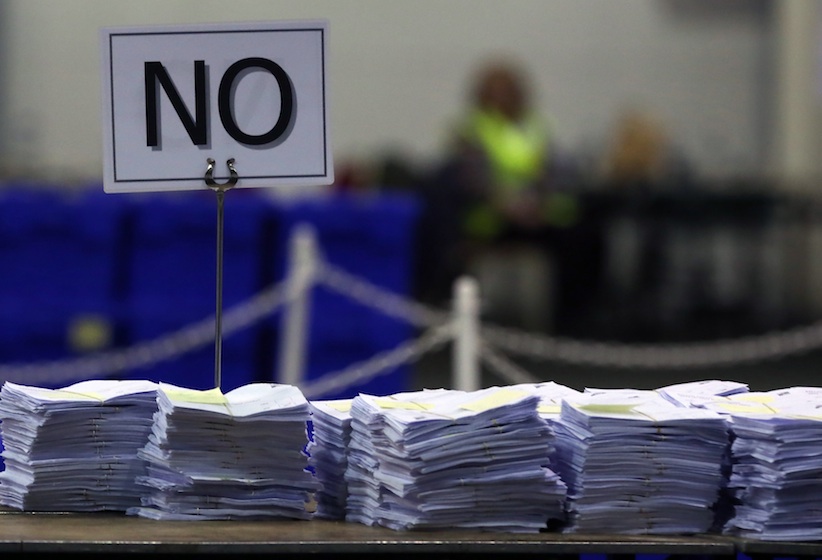

Scotland has had its say, and the United Kingdom has been saved—for now. The No victory in the independence referendum made me happy, on balance. But if I look closely at my reasons they turn out to be quite personal, even prejudicial.

Awhile back I had occasion to look more closely into my family tree, as some people do when they hit middle age. Most of my ancestors came from the British Isles about a century ago, including the Coshes from southwest Scotland, but I had never tried to divide them up mathematically between England and Scotland. It turns out I’m about one-third English and one-third Scottish.

That sounds like a math joke (powers of three?) but it’s very nearly true—about 11 of my 32 great-great-great-grandparents come from either side of the border, or practically right on it. That seemed to make a certain point about the absurdity of putting Hadrian’s Wall back up in Britain. But perhaps only to me. So just what is the proper place of nationhood in politics? This is surely a question that has to be solved by some appeal to higher principles, if any two people with different backgrounds are going to agree on a social order. Yet answers prove elusive, as the history of Canada demonstrates.

I came to a libertarian ideology quite early in life and have never abandoned it. I am opposed to the initiation of violence. I think governments are always and everywhere in danger of reverting to the status of gangs. I believe that taxation is essentially theft and should not happen without the kind of clear moral justification that would excuse a theft. I believe in virtually unrestricted liberty of speech and the press; I believe property is a sacred foundation of society.

None of which really helps me answer questions about nation-states. As I’ve gotten older and immersed myself more deeply in the study of history—while watching libertarian principles become steadily more respectable—I’ve begun to realize that the issues you can resolve by simple appeal to a libertarian ideology are the low-hanging fruit of the political universe. Libertarianism helps you see that things like dairy supply management or Internet content policing are shocking absurdities. But does it settle issues like abortion, or immigration, or tort reform or voting criteria?

Not on its own. It dictates that human lives should not be taken without due process, but it doesn’t tell you whether murderers ought to be hanged. It insists that persons should be allowed to organize for collective aims, but does not say that a legal system must have limited-liability corporations. It says private individuals should be allowed to use whatever money they want—but not what kind of money is really best.

Other people with a basic ideology formed in youth must have the same experience. (A political ideology is all the more suspicious if the answers it offers to hard questions are complete and automatic.) Britain still has people who are willing to call themselves socialists, and the question of Scottish independence tied them in knots: some argued for continued trade-union and Labour Party “solidarity” between Glasgow and London, and some said that small is beautiful and Scotland is different. Professed liberals had the same predicament. They like big, muscular government—but it was liberals who invented national self-determination.

Libertarians have an instinctive horror of larger states: what we call libertarianism sprouted in Cold War-era fears of a worldwide superstate, which we now call “paranoid” in retrospect only because we forget how popular the idea was. The world is, in general, better off with more states. Ideally there will always be refuges from authority, and more states mean more potential laboratories for libertarian success and functioning non-state institutions. (One thinks of the increasing number of European towns without traffic signals, all of whom had to fight the general prejudice in favour of laws and rules we have never tried to do without.)

But there is a level of state size below which libertarian principles cannot be practised. A state must have the means of collective self-defence, whatever principles it is founded upon, and total anarchy is not a stable equilibrium. This is the point at which the concept of the nation comes into the argument. But nations are all more or less fictions. The problem, in Scotland or Quebec or Catalonia or Tamil Nadu, is that a) they are fictions people believe in strongly and b) often they believe equally strongly in irreconcilable fictions.