Visualizing First Nations deprivation with boxes & whiskers

Sometime last year I found myself wondering about the effects of residential schools on the younger generations of aboriginal Canadians. The schools have more supporters than you might think, more than almost anyone likes to admit, amongst former attendees; the resentment felt toward them by those who had terrible experiences is matched by the ferocity with which Indian families agitated to keep the better ones alive late in their existence. We have chosen to take a monolithic view of the residential schools as a bad idea, full stop—to the point at which any educational intervention into Indian welfare that smacks of paternalism will now be run from as if it were a rabid grizzly. (Just for starters, the scale of the residential schools was obviously one of the problems; if there had been four, instead of 80 or more, they could perhaps have been run with some professionalism and accountability.)

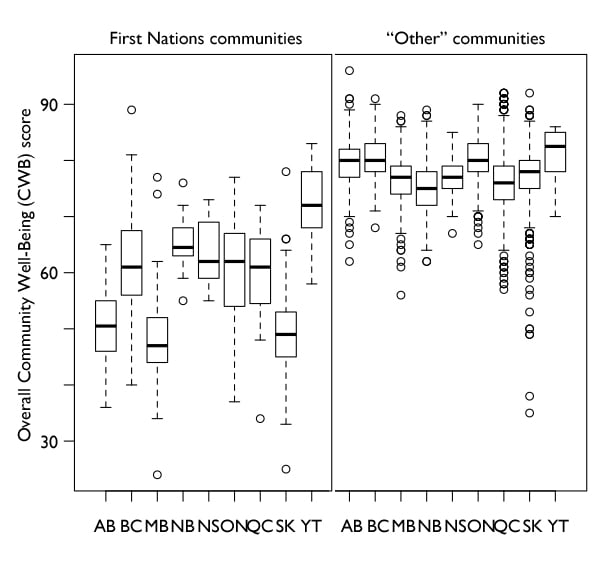

Boxplot of CWB indices for FN/”other” communities by province

Share

Sometime last year I found myself wondering about the effects of residential schools on the younger generations of aboriginal Canadians. The schools have more supporters than you might think, more than almost anyone likes to admit, amongst former attendees; the resentment felt toward them by those who had terrible experiences is matched by the ferocity with which Indian families agitated to keep the better ones alive late in their existence. We have chosen to take a monolithic view of the residential schools as a bad idea, full stop—to the point at which any educational intervention into Indian welfare that smacks of paternalism will now be run from as if it were a rabid grizzly. (Just for starters, the scale of the residential schools was obviously one of the problems; if there had been four, instead of 80 or more, they could perhaps have been run with some professionalism and accountability.)

It is hard to be sure that this is fortunate. And it is hard to be sure that it is helpful, for if there are other systematic explanations for Indian poverty and social issues, the “it’s all because of those hellish residential schools” explanation might cause us to overlook them. The schools have been shut down for a long time now; they can’t be blamed for the remainder of eternity, any more than I can attribute my incompetence with money to the Highland Clearances. Though maybe I should give it some thought.

Anyway, it turns out that there are surprisingly detailed data concerning Indian social welfare. The federal Aboriginal Affairs department collects and calculates a “community well-being index” for all Canadian communities, and has used the numbers to identify top-performing Indian bands, in order that policy lessons might be extracted from them. The latest index data are old, dating to the 2006 census, but visualizing them still teaches useful things about Indian societal health.

The tool I used is called a “box-and-whisker plot”, or, for short, a “boxplot”. The Great Tukey (peace be upon him) gave the boxplot to us, describing it as a “microscope” for data analysis. But presenters of statistical information for public consumption don’t show boxplots very often, because their features are not too intuitive. It lets you put series of numbers side-by-side and eyeball them for differences in the distributions. The parts of a boxplot are thus: (1) a box around the “interquartile range”, or the middle half of the data; (2) a line through the box at the median; (3) a “whisker” usually extending outward from the box up to 1.5 times the interquartile range from the median (but no further than the furthest actual data); (4) individual dots for outlying data points beyond the whisker. The length of the whisker was chosen by Tukey so that data matching a normal, symmetrical bell curve would have few outlying points, no more than 1% of the sample; many dots are thus a convenient quick indication that a data set is non-normal. (That’s important for statisticians because it rules out further analysis techniques that assume normality.)

I’m not going to quiz you on all that: a boxplot is not too intuitive, but it’s intuitive enough that you can just look and feel. So here’s a picture of First Nations well-being (as of 2006) broken down by province, with tiny P.E.I., largely FN-free Newfoundland, and Inuit communities set aside:

Why did I want to look at this information this way? Because Canada actually performed an inadvertent natural experiment with residential schools: in New Brunswick (and in Prince Edward Island) they did not exist. If the schools had major negative effects on social welfare flowing forward into the future we now inhabit, New Brunswick’s Indians would be expected to do better than those in other provinces. And that does turn out to be the case. You can see that the top three-quarters of New Brunswick Indian communities would all be above the median even in neighbouring Nova Scotia, whose FN communities might otherwise be expected to be quite comparable. (Remember that each community, however large, is just one point in these data. Toronto’s one point, with an index value of 84. So is Kasabonika Lake, estimated 2006 population 680, index value 47.)

On the other hand, and this is exactly the kind of thing boxplots are meant to help one notice, the big between-provinces difference between First Nations communities isn’t the difference between New Brunswick and everybody else. It’s the difference between the Prairie Provinces and everybody else including New Brunswick—to such a degree, in fact, that Canada probably should not be conceptually broken down into “settler” and “aboriginal” tiers, but into three tiers, with prairie Indians enjoying a distinct species of misery. (This shows up in other, less obvious ways in the boxplot diagram. You notice how many lower-side outliers there are in Saskatchewan? That dangling trail of dots turns out to consist of Indian and Métis towns in the province’s north—communities that are significantly or even mostly aboriginal, but that aren’t coded as “FN” in the dataset.)

I fear that the First Nations data for Alberta are of particular note here: on the right half of the diagram we can see that Alberta’s resource wealth (in 2006, remember) helped nudge the province ahead of Saskatchewan and Manitoba in overall social-development measures, but it doesn’t seem to have paid off very well for Indians. This isn’t a surprising outcome, mind you, if you live in Alberta; we have rich Indian bands and plenty of highly visible band-owned businesses, but the universities are not yet full of high-achieving members of those bands, and the downtown shelters in Edmonton, sad to say, still are.

These little boxes go some way toward explaining why the Harper government’s focus on Indian-band accountability may make less sense to Ontarians than it does to Albertans—or why Harper’s prairie base might have had a different reaction to the conditions and the controversy in Attawapiskat than Eastern voters did. It is data of which everyone should be aware, and I wish there were an easier, more natural way to depict it. I’m also curious about how the same data will look once they’re compiled from the 2011 census, heaven knows when.