French breast implants: a Science-ish saga?

It turns out we don’t know much about how risky implants are

Share

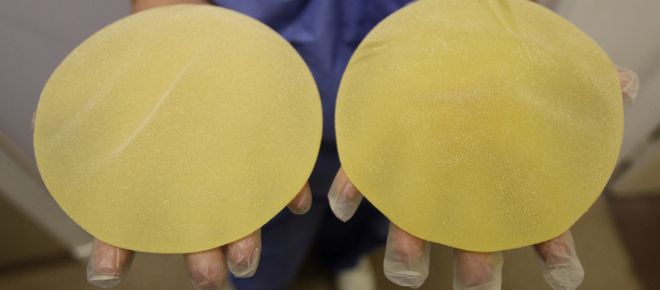

Since December, health authorities around the world have been scrambling about what to do with women who have French-made Poly Implant Prosthesis (PIP) breast implants lodged in their bodies. After being approved for market, it recently emerged that PIP implants were filled with non-medical grade silicone—unbeknownst to regulators—and that their manufacturer had got rid of an outer skin to keep the implants from leaking and breaking.

What’s science-ish about this?

Watching different countries respond to the news has been a science-ish drama in the making. In December, the French government advised 30,000 women with PIP implants to have them purged on the public purse. Health authorities said there was a possible link between the implants and cancer, citing the deaths of women who had the dubious implants.

Since then, just about every country that had previously authorized PIP implants mounted a different response to the news that silicone meant for mattresses was now in the chests of women around the world. Dutch health authorities, for example, have said women should have the implants taken out because of what they think is a high rupture risk. This was a reversal from an earlier call to have the implants checked by a doctor, but not necessarily removed.

The British Health Secretary, on the other hand, said, “there is not sufficient evidence to recommend routine removal.” Indeed, the U.K.’s review of the evidence concluded there was no link between the implants and cancer, and that they can’t say whether the PIP implants are particularly prone to rupturing. Interestingly, though, the government decided that worried women who got the implants through a public clinic can have them removed and replaced on the government’s dime.

Not so, however, for patients who got their new breasts from private clinics. Here, the government has called on those doctors to foot the bill. (At least one clinic, which fitted nearly 14,000 women, predictably said it sees no cause for concern and won’t replace the questionable implants.) Of course, this situation is muddling for patients who went to private clinics which have since closed or refuse to remove the faulty implants.

Nearby Wales, by contrast, has offered to pay to have the PIP breast implants removed and replaced—even those that were fitted privately.

More examples still. The Czech Republic followed France’s lead. Cautious Germans decided PIP implants constitute “possible health risks” and advised implanted women to have them taken out as soon as possible. The Bolivian and Venezuelan governments have said they’d take out the implants, but have not made this a recommendation.

In Canada and the U.S., PIP implants never even made it to market. (Health Canada and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health have not yet returned my requests for comment.)

This variation in policies raises questions about how public health decisions are made, and how scientific evidence factors into policymaking. It’s also interesting to see how risk is interpreted differently across cultures and borders—even within the same country. (Of the U.K.’s emphasis on the absence of a link to cancer, anthropologist Alexander Edmond, who wrote this intriguing editorial, noted, “That’s a very narrow definition of what risk is. It’s not really the one consumers or patients have in mind.”)

Of course, medicine is an exercise in balancing risks and rewards. On that matter, Health Canada, which has authorized saline- and silicone-filled implants, offers this guidance on its website: “No medical device is 100 per cent safe and effective. Health Canada’s licensing of a medical device does not mean the device is risk-free. Rather, it means the device has the potential to provide benefits, and the risks have been reduced as much as possible. The risks that remain are always explained in the labelling.”

Better breast implant evidence

The diversity of responses to the PIP implant problem may also be a reflection of the rather murky evidence base for these medical devices. Science-ish could not find any robust, scientific reviews of the health effects of breast implants, and most studies on the subject are funded by the manufacturers of the silicone inserts. In a report about detecting breast implant rupture, by the Quebec agency responsible for health services and technology assessments, the author noted, “The current state of knowledge reveals a lack of scientific data demonstrating the toxicity of silicone breast implants or the adverse health effects of silicone in women. This said, breast implant rupture is a local complication that has mainly esthetic consequences. However, if silicone turns out to be toxic to women, research should focus on the very use of breast implants rather than on implant rupture, for it is recognized that silicone migrates by sweating, even from intact implants, and that an implant shell is a source of silicone exposure.”

On that note, a 2010 commentary in Reproductive Health Matters, by the president of the National Research Center for Women and Families in the U.S., stated that the evidence base for breast implants is dubious, and that the risks related to this surgery aren’t often communicated to patients. “(The Center) received thousands of calls and e-mails in recent years from women all over the world who tell us that their plastic surgeons did not adequately warn them about the risks of breast implants or fully advise them about their options when problems arise.”

The author goes on to say that, prior to 1990, patients were told implants would “last forever” despite the absence of long-term data. Today we know that the average implant stays in tact for about ten years, though some break within months or stay put for longer. More significantly, most regulatory approvals for breast implants were based on short-term data and the promise of more robust studies down the line. But a newly published editorial in the British Medical Journal notes studies with longer time frames may never see the light of day: “Thousands of women enrolled in breast implant studies to evaluate rare complications have simply disappeared. Postmarketing studies, requested by the FDA in 2006, have lost so many of the women they were supposed to follow up that they are unlikely to offer any insight into the long term safety of devices.” The author asks what patients have been told “in light of insufficient evidence? It seems that many women may have been told breast implants were safe, but this was and is impossible to know.”

So there we have it. Only time will tell whether the hysteria around the French breast implants is warranted. For now, let’s hope this doesn’t amount to a public health tragedy and use this science-ish saga as a lesson: patients, physicians, and policymakers should question the evidence behind relatively new medical devices, and the way health regulators monitor the manufacturers of these devices. As with PIP, are they delivering the products they promise in the first place?

After my year-end call for submissions, you told me you were most concerned about two things: whether WiFi poses health risks, and which is the most effective diet for losing weight, based on the evidence. Stay tuned for the second installment on diet.

Science-ish is a joint project of Maclean’s, The Medical Post, and the McMaster Health Forum. Julia Belluz is the associate editor at The Medical Post. Got a tip? Seen something that’s Science-ish? Message her at [email protected] or on Twitter @juliaoftoronto