The truth about superbugs and antibiotics

There’s good news (the problem is fixable) and bad (a dry drug pipeline)

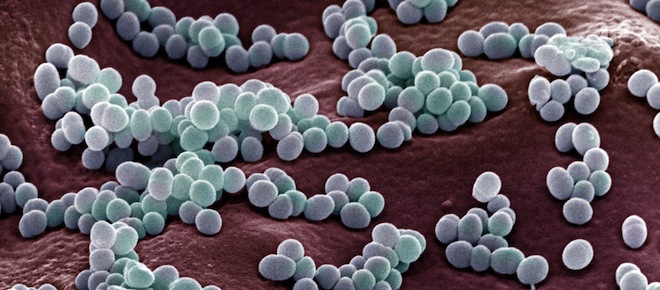

MRSA colonies on blood agar plate

Share

In a post about the most outrageous attacks on science in 2012, Science-ish asked you to pick the topic you’d like to see tackled first in the new year: you wanted the truth about antibiotics and superbugs.

It’s no wonder. The popular discourse about these rapidly multiplying, drug-resistant microbes is pretty freaky. An investigation by CBC’s Marketplace found deadly bacteria, like C. difficile, lurking in hotel rooms. Other stories have revealed that they are waiting to cuddle up with you in hospitals, and even peppering your chicken dinner.

Meanwhile, the British Medical Journal has reported that the dangers of superbugs may be over-hyped, turning poor germ-avoiding patients into hospital cleaners. But you, dear readers, know the cleansing light of evidence can wash away some of those fears. Here’s what the latest research tells us about antibiotics and superbugs:

MIND YOUR CHICKEN

While there’s a lot of popular debate about the over-use of antibiotics in the agricultural sector, and to what extent this impacts human health, according to infectious disease expert Dr. Scott Halperin, “This is an area where everybody except people in the agricultural sector think there’s no controversy.”

It’s okay to treat infected animals with antibiotics, Halperin continued, but the wanton use of them to enhance growth in factory-style feedlots “is just not a good idea from a antibiotic-resistance standpoint.” Animals develop resistant bacteria–those get into the food-chain–and there’s good evidence that they colonize people and make them sick. (Read up on antibiotic-resistant enterococci and staphylococci here.)

For these reasons, the European Union banned antibiotics for growth promotion (but not infection control) in 2006. In Canada, it’s still largely a free-for-all. Our government does not regulate or track the use of these drugs in farming.

LESS IS MORE

It’s now a scientific truth universally agreed upon that the more antibiotics you take, the more likely you are to grow microbes that become resistant and contribute to the pool of superbugs. The proliferation of super bacteria was fuelled by magical thinking during the early days of antibiotics, which first emerged in the 1940s. They were potent cures, stopping bacterial infections such as pneumonia and tuberculosis that routinely killed people, and making otherwise seemingly impossible feats in medicine—like transplants—commonplace. These little miracles were believed to have few side-effects, too. So for a long time, doctors thought it was best to err on the side of caution, and prescribe more and for longer courses.

Now, we know that more antibiotics means more resistance. There’s a movement afoot to get doctors to prescribe judiciously, and some countries are even looking at banning certain antibiotics all together. Other new evidence-based rules of thumb, which Science-ish learned about at a conference for family doctors, include: If you’ve been well for 48 hours, you may be able to stop taking your antibiotic; for many antibiotics, five to seven days is sufficient (instead of the classic seven to 14 prescriptions); and don’t use the same antibiotic—or even the same class of antibiotics—within three months of your last round.

RISE OF THE SUPERBUGS

There are networks across Canada that track superbug infections, and according to infectious disease experts, we are seeing more of these resistant bacteria emerge over time. “Name a bacteria and there’s an antimicrobial resistance problem,” said microbiologist Allison McGeer. Gonorrhoea is becoming multi-drug resistant. Ditto TB. A new superbug called NDM-1 from South Asia is poised to attack hospitals here. And this isn’t only a hospital problem. These bugs are emerging in the community, as well.

A DRY DRUG PIPELINE

To make matters more interesting, the pipeline for antibiotics is dry. As McGeer put it, “The last new class of antibiotics approved in Canada was in the 1970s.” That’s 40 years ago! For a time, pharmaceutical companies stepped away from antibiotic development because of a perceived lack of need and their relatively low potential for profitability. Now, there’s a gap. We need them, but they take 15 to 20 years to bring to market. “There are a lot of people working on exciting, new, different kinds of antibiotics, but those are still in the pre-clinical phase—not used in animals and humans yet,” said McGeer. “There’s no question we have, in the next decade, a problem because the pipeline is hitting a dry patch.”

THE PROBLEM IS FIXABLE

Still, there’s no need to seal yourself off in a vermin-repellent container or move to a frozen climate where bacteria can’t thrive. “Remember, we once lived in a world without antibiotics,” McGeer added. “It’s not the end of the world. But it does mean that people who go into hospital for surgery who would have otherwise been fine, will die. And our life expectancy might decrease.”

The good news: This problem is fixable. More rational prescribing by doctors, more understanding among patients that antibiotics aren’t a panacea for every sickness, some action by regulators to minimize the use of antibiotics in agriculture, as well as open-lab collaborations for better antibiotic development, can all help. And as McGeer added, “Prevention is better than treatment.” Wash your hands, get your vaccines, take safety precautions when cooking and handling food, and stay home when you’re sick. Doctors’ orders.

Science-ish is a joint project of Maclean’s, the Medical Post and the McMaster Health Forum. Julia Belluz is the senior editor at the Medical Post. Got a tip? Seen something that’s Science-ish? Message her at [email protected] or on Twitter @juliaoftoronto