Looking back on the many lives of Robin Williams

Jaime Weinman examines the comedian and actor’s incredible career and personal history

August 11, 2014 – File – Oscar winner and comedian Robin Williams has died at 63. His publicist wouldn’t confirm suicide, but issued a statement. ‘Robin Williams passed away this morning. He has been battling severe depression of late.’ Williams, who won an Oscar for his supporting role in ‘Good Will Hunting,’ will reprise his role as Theodore Roosevelt in the third installment of ‘Night at the Museum’ this December. He had recently signed on to reprise his beloved role as Mrs. Doubtfire in a sequel. Pictured – 1980 – ROBIN WILLIAMS studio shot. (Credit Image: © Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Share

Chapter I: The Rising Star

The world of Los Angeles comedy clubs in the 1970s can seem a little romantic now—mostly because the Baby Boomers were getting into comedy at the time, and they romanticize everything. Still, for a comedian like Robin Williams, there was something magical about that place. Born to a wealthy family in Chicago, he had moved with his parents to San Francisco when he was a teenager in 1968, right into the midst of the hip Baby Boomer culture that permeated the city. By the time he was ready to leave the hippie capital, he was already recognized as a leading young talent who could do for comedy what other San Franciscans had done for music. But you couldn’t stay in San Francisco and hope to take over the comedy world. L.A. was the place, with famous clubs like the Comedy Store and the Improv, where old agents hung out to discover young comics.

In L.A., Williams built his material, slowly letting a reputation grow by word of mouth among comedy experts, out of sight of the general public. The public would come later; comedy clubs were for comedy fans, and those fans liked to be able to spot a coming star. At least some of them knew they’d spotted one when Williams auditioned for the Improv. The routine, according to New York magazine, was “a five-minute bit about masturbating and watching his penis grow so big he could never leave his room.” As comedians say in their famously violent language, he killed.

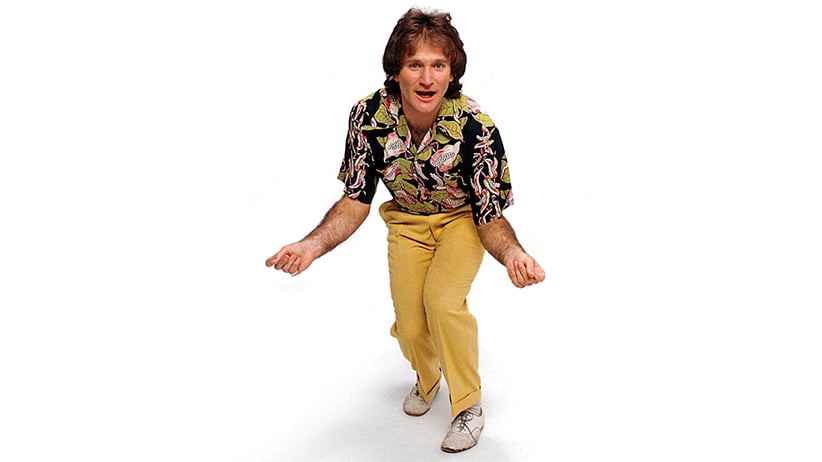

Influenced by Richard Pryor and Jonathan Winters, as every comic in America was at the time, he was a manic mugger and a guy who wove a collage of pop-culture references and impressions into everything he did; people were already complaining then about shortening attention spans, and Williams was a proud child of television, who remembered everything he’d ever seen and was feeding it back to his audience in short bursts, from his stock voices (William F. Buckley was a favourite) to his cartoon references. He was the kind of guy you’d describe as “on speed,” whether or not you knew which drugs he was actually taking.

This was considered a golden age of stand-up comedy, with comedians like Pryor revolutionizing the business, and upstarts like Letterman and Leno playing the comedy clubs and developing their art. Best of all, there were places where a comedian could get a wide audience for his (usually his) work. The big prize was a guest spot on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show back when The Tonight Show was in L.A. Williams didn’t get that, but he got some smaller prizes: an invitation to appear on a short-lived variety show starring none other than Richard Pryor, and a spot on an equally short-lived revival of the ’60s sensation Laugh-In.

Then the big break came in the spring of 1978, from what would have seemed like just another small prize—but maybe that’s one of the things that makes a true star: the ability to grab opportunities where no one else can see them. Happy Days was doing a show where Richie meets a space alien. Why? Because a kid said he liked Star Wars, and that kid was the son of Happy Days creator Garry Marshall, who promptly ordered his writers to have the Fonz duel an alien named “Mork” for custody of Ron Howard. The original actor cast as Mork became unavailable (lucky for him, his name isn’t known). Williams got the part because he was in an acting class with Marshall’s sister Penny, who recommended him to Happy Days’ casting director, Marshall’s other sister, Ronny. When he had the role, he killed again. Every actor can be seen just trying to keep a straight face when he’s around. Henry Winkler said he gave up any hope of competing with this guy and just tried to concentrate on not laughing when the camera was on him.

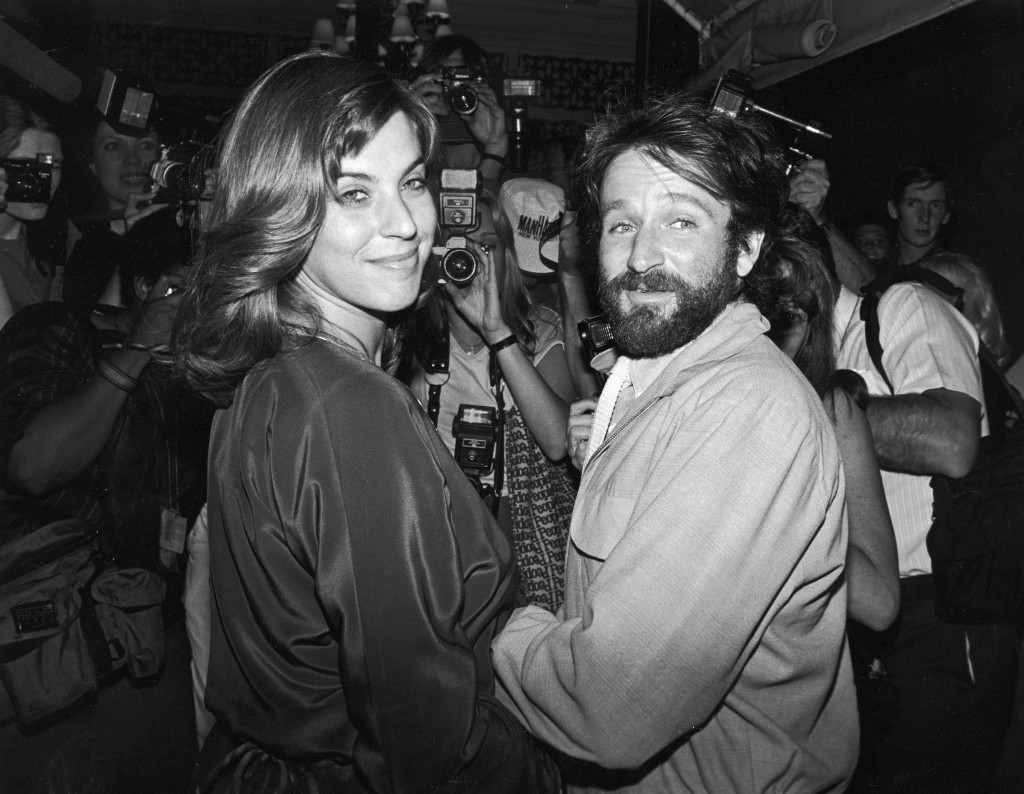

Suddenly, a silly little show became the start of something big. As if to signal that he had finally arrived, Williams married his girlfriend, Valerie Velardi, in the summer of 1978, soon after ABC picked up the show that Marshall originally pitched as “The Mork Chronicles.” The show followed Mork as he learns about life on Earth and has sexual tension with a young woman in Boulder, Colo. (“Why is he in Boulder?” an ABC executive asked. “Because my niece lives there,” replied Marshall, “and if I’m going to take a trip, I might as well go where I know somebody.”) The premise wasn’t much, but it was all built around Williams; the supporting cast existed to feed him straight lines and laugh at his jokes. “I knew he had to be played loose,” Marshall told writer Sally Bedell. “He had to be able to go any way.” It’s said that it was because of Williams that sitcom film crews started using four cameras instead of the usual three; there had to be one camera just to follow him wherever he went, disregarding whatever blocking the director had worked out.

Mork & Mindy was a phenomenal success for a first-year series; there was lots of merchandise, and it was all because of Williams, who managed the feat of appealing to kids and adults at the same time. Especially popular were the tags at the end, where Mork would stand in front of a black background and report on what he’d learned. Kids liked them because Mork wore his red spacesuit and said his catchphrase, “nanoo nanoo,” but these tags were an opportunity for Marshall and Williams to indulge their social consciousness, get a little personal. In a now-famous and painful tag, Williams nearly broke character and spoke about the pressures of fame and how “some people just can’t take it,” his voice breaking when he mentioned the murder of John Lennon. The mix of kids’ stuff, semi-improvised shtick and mild preachiness gave the series what Bedell called “an unusual following that included a high proportion of characteristically non-viewing college students, as well as a loyal crowd of ministers who regularly lifted the tags for their sermons.” Behind it all was Williams, suddenly the biggest comedy star in the world.

For a year, anyway. Then, in the fall of 1979, came a big collapse, both for the show and for Williams. The series underwent a disastrous retool in the second season, with new supporting characters added and more sexual humour. Part of this was due to Williams, who was already getting tired of playing the same character every week. He found it silly that Mork was still naive about Earth after a year living on the planet, he told the writers. Make him smarter, hipper, wiser. The writers felt that if Mork wasn’t naive, there was no show. Williams wasn’t in a good mood, partly because of the easy temptations of drugs and alcohol, partly because his marriage to Velardi was already on the rocks, and partly because he just couldn’t be happy when he wasn’t performing. “He was no prize package at that point,” comedian and manager David Steinberg told New York. “There were four or five personalities trying to get out.”

The result was that the writers turned the show into an uneasy mix, with Williams sometimes playing Mork and sometimes playing a character closer to himself—if there were such a thing. The show stopped being a hit and never found its way back, not even with Williams’s idol Jonathan Winters stepping in to play Mork’s son (don’t ask). Williams’s cocaine problem at the time, while not widely reported on by the decorous press, may have contributed to the decline of the show, but, then again, he was only one of many, many people in show business at the time who couldn’t do without cocaine. “Cocaine,” he said in one of his most famous jokes, “is God’s way of letting you know you have too much money.” But the drugs wouldn’t have been such a problem if the show had still been funny. It was cancelled after four seasons, 1978’s Mork-mania and merchandising bonanza long forgotten.

Williams already had found an out for himself, a new place for his career to go. He found it in a 1982 movie called The World According to Garp—a title that is probably more familiar now than either the film or the book it’s based on.

Chapter 2: The Star Reborn

The World According to Garp was not Williams’s first big movie role; that was Popeye, a well-intentioned but financially disastrous comic strip film. Director Robert Altman got most of the praise and blame for that one, and Williams was hard to recognize under all that makeup. Garp was Williams’s bid for real movie stardom, and it was not at all the kind of thing you’d have expected him to take, whether you considered him an edgy stand-up comedy motormouth or a kid-friendly sitcom alien. The film was based on a surreal bestselling novel by John Irving. The title character gets to dress in drag, but it’s to attend the funeral of his murdered mother. It’s a serio-comic role in a movie that is only partly a comedy. It’s an acting role, in other words—and successful TV comedians don’t usually do acting roles when they haven’t even had a hit movie yet.

But Williams, unlike some of the other TV comics who transitioned to movies—including his close friend John Belushi—didn’t seem interested in making pure comedies, movies that followed or subverted the traditional comedy formula. He wanted to act, and he wanted to act without giving up his comic ability. This was a guy who dropped out of Juilliard because the teachers were turned off by his idea of improvised acting: it was comedy, not acting, they sniffed. Williams’s movie career became an exercise in showing they were wrong: that he could do serious acting and dress in women’s clothes and make pop-culture references, all at the same time.

Maybe his choice of movie roles reflected the fact that he himself was becoming more serious. The rise of the religious right in the form of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, something that surprised and terrified a lot of people in Hollywood, was particularly disturbing to Williams. He made the Moral Majority and its adherents a major target. “The potential scares me,” he told New York. “That’s why I like to take the wind out of their sails as much as possible.” Though his personal life had stabilized in some ways—he gave up substance abuse for the birth of his son Zach in 1983, recalling later: “I didn’t want to miss it because I was coked up or drinking”—he and his wife had drifted further apart. He was a more serious person, and perhaps needed a more serious acting style.

It might also just be that after Mork & Mindy was cancelled and he concentrated on his movie career, he found people liked him less when he was playing pure comedy. The Survivors, a 1983 buddy farce with Walter Matthau, was a flop. The following year, he made Moscow on the Hudson for director Paul Mazursky, playing a Russian who defects to the U.S.: Again, the mix of comedy with drama, silliness (the accent, for one) and pathos was a hit. People liked him this way. When comics such as Andy Kaufman did movies, they mistakenly chose vehicles that tried to be funny all the way through. But audiences didn’t simply want to laugh at Williams; they wanted to like him. They wanted to feel for him. Mork was popular, partly because of those semi-serious little tags at the end, and Williams had to incorporate something like that into his movie persona.

So there were at least two versions of Robin Williams. There was the version he presented in his stand-up act, which was really an infinite number of versions. The wild man, the free-form improviser (even if some of the seemingly improvised bits would get repeated from time to time), the lovable loose cannon. This was also the version we saw on talk shows, but it wasn’t something that could be incorporated into movies, it seemed, where a more placid Williams was the order of the day. While he had given up substance abuse after the nasty shock of Belushi’s death, and he was establishing himself as a movie star, he wasn’t yet a superstar. He still couldn’t bring certain parts of his audience—the fans of his stand-up, the kids who loved him as Mork—into the theatres.

Then, one movie unlocked the formula for making Williams not just a star, but an enormous, global-dominating star. This was 1987’s Good Morning, Vietnam, based on the life of a radio personality who himself admitted he was never anywhere near as good as Williams’s recreation of him. The story of Good Morning, Vietnam, being a war story, incorporated drama and pathos, with Williams facing down bombs and the insensitive military machine. But when Williams was in the radio station doing the show-within-a-show, he could let loose with everything he’d learned to do in stand-up. There it was in that movie, which became one of the biggest hits of 1987, as well as bringing Williams his first Academy Award nomination. Two versions of himself, the stand-up comic and the actor, existing side-by-side in the same film. He didn’t have to choose. Neither did the audience.

Chapter 3: The Superstar

The ’90s was a new era for Robin Williams, professionally and also personally. He and Velardi divorced in 1988 and, the following year, he married Marsha Garces, Zach’s former nanny, who was already pregnant with his second child. They had two children together, and she also became his assistant, producer and tough-love talker: “You’ve got two great careers, you’re really intelligent, you’re healthy, you’re strong, you’re handsome,” she recalled telling Williams, “and you’re totally depressed. You’re an adult, Robin; pull it together!” Pulling it together isn’t actually a cure for depression, but his life seemed to be on track, and his career was, too, more than ever.

You know that Robin Williams was a big movie star in the 1990s, but, unless you were a moviegoer during that period, you don’t know just how big a star he was during the 1990s. You may know the titles of the films—The Fisher King, Mrs. Doubtfire, Patch Adams—but, from today’s vantage point, they don’t look like the resumé of a gigantic star; they mostly look like middle-of-the-road, medium-budget projects that today’s stars do in between blockbusters. But, in the ’90s, sentimental comedies like The Birdcage were blockbusters—at least, when they were able to get Williams to star.

The era of Williams’s ’90s superstardom actually began in 1989 (but then, so did a lot of ’90s culture). The film that launched it was Dead Poets Society, about a teacher who tries to help a bunch of prep-school kids break loose and let their minds run free. This is the sort of plot that, today, would be an indie film, at best. In 1989, it was the fifth-highest grossing film of the year—less than Batman, but more than Lethal Weapon 2. This was the last era in which you could still have an enormous summer hit without a lot of things blowing up, and Dead Poets Society was the quintessential feel-good, you’ll-laugh-you’ll-cry, non-action blockbuster.

It presented all the sides of Williams, and all his potential audiences, unified at last. Dead Poets Society is basically a drama aimed at grown-ups, even if the script isn’t particularly grown-up in its Manichean morality (Williams is good, repression is bad). But it’s also an anti-authority comedy where the cool new teacher butts heads with the stuffy headmaster. It appeals to kids because it’s a film about how unpleasant school can be, and presents the cool teacher of their dreams. And it allows Williams to be both a character and a performer: He plays it straight in most scenes, but, in the classroom lectures, he gets to do a modified, in-character version of the Williams we know and love from those talk-show appearances.

He also gets to show that he’s an actor who doesn’t mind sharing a movie with others. Most of his other successes had been solo: Mork & Mindy was mostly just Mork, and no one remembered who else was in Good Morning, Vietnam. But Dead Poets Society was as much about the kids in Williams’s class as it was about Williams. He didn’t have the kind of star ego that insists he get all the good lines, all the good moments, and many of his subsequent successes would have him give a lot of that over to a less bankable star: The Fisher King is really about Jeff Bridges, while in The Birdcage, based on the French film La Cage Aux Folles, he took the less show-offy role, giving the flashy part to Nathan Lane. As long as the character incorporated the different things we wanted to see from Williams, we didn’t need him to be “on” all the time onscreen, as he was when he played himself.

Even in Aladdin, probably his most famous role to people of a certain generation, he’s not the star of the film: The genie doesn’t show up until a third of the way through, and he’s a loyal friend and sidekick who wants only what’s best for the title character. This is Williams as people love to think of him from Dead Poets Society, the magical funny man who wants kids to have fun and learn to love themselves. No wonder children loved him, even before Aladdin was released.

Because people loved him so much in Aladdin, he almost single-handedly changed the way animated movies were cast. Before Aladdin, there was a consensus that these movies shouldn’t rely too much on star voices, and that if they did cast a star, the film shouldn’t publicize the star’s involvement too much. Focus on the character, not the actor. This was impossible for the genie, because he was just Robin Williams, doing all the familiar Williams bits—the comedy, the impressions, the pathos—with the genie’s animator, Eric Goldberg, keeping up with the anachronistic bits that Williams ad-libbed, including his beloved William F. Buckley impersonation. It’s because of that piece of casting that we now have animated films that not only seek out stars, but put their names above the title and openly base the characters on the actor’s persona.

Between changing the world of cartoons and ruling the world of the serio-comic popcorn movie, Robin Williams had a pretty good decade. He wasn’t immune to flops; a reunion with Good Morning, Vietnam director Barry Levinson on the fantasy Toys was a disaster. But no one else could have made a monstrous international hit out of Mrs. Doubtfire, another story perfectly tailored for the multiple versions of Williams: He plays an actor who does rapid-fire verbal comedy and cartoon voices, he dresses up as a woman for slapstick fun, and it’s all for the sake of connecting with the children he loves. This is why everyone went to see him back then. He could make you laugh and he could make you feel and, unlike, say, Jerry Lewis—a similar performer, in some ways—he created smooth, seamless transitions between the serious and funny bits. Some comedies are fun but featherweight; Robin Williams comedies had something for everyone, a rich meal for the full age range of the moviegoing world.

Williams’s superstardom didn’t last. Superstardom usually doesn’t. The collapse of the non-action blockbuster, not to mention the fact that comedies don’t do well in the increasingly important overseas market, made it harder to do the kind of well-made studio entertainment he specialized in. He made a bunch of stinkers in the late ’90s, including the ill-considered Holocaust comedy-drama Jakob the Liar, and Bicentennial Man, which proved that a movie about a futuristic robot is not one of the things where the Williams formula applies particularly well.

By then, Williams had already prepared himself for the transition out of movie superstardom. Again, putting opportunity before ego, he took a secondary role in Good Will Hunting, winning an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor and establishing himself as a fine character actor, even before his days as a headliner were over. His personal life changed again, as it always seemed to when he was making a career transition; his marriage to Garces broke up in 2008, and he and his new wife, Susan Schneider, settled down in a residence in San Francisco, the town that was closest to his heart and his style.

In 2002, he did a very successful one-man show on Broadway. The 2000s saw him do a mix of dramatic films, voice acting (something he’d mostly given up after a dispute with Disney over Aladdin) and solid character parts, such as Teddy Roosevelt in the Night at the Museum movies: The latest movie in that series is already finished, and will serve as one of his memorials when it comes out this December. He had a TV series, The Crazy Ones, that lasted only one season but earned him generally good reviews for his performance, and he was planning a Mrs. Doubtfire sequel. One can’t go looking to Williams’s career for clues to his inner demons: This was an exceptionally well-managed, well-handled career. A person can be perfectly good at managing his work and his life, and still be tormented in ways we can never understand.

It’s Williams’s career that lives on now, in the form of the work he did and the persona he created. Like that of every great film comic, that persona will live on, even if most of the films themselves aren’t watched as much as they used to be. You know what Charlie Chaplin or Jerry Lewis are like, even if you’ve never seen their films; the same thing is true of the words “Robin Williams.” When you say that name, people think of a man who can’t stop being funny, can’t stop talking, just can’t stop—but who also has a social conscience, loves children and wants everyone to be happy and at peace with themselves. That is a character everyone can love. That’s someone everyone, including Robin Williams, would probably like to be. It’s someone we will remember for as long as entertainment exists.

Remember the legacy of Robin Williams with a free digital edition of our special commemorative issue, available for download on your iPad. For subscribers, check the newsstand in your Maclean’s app. For new readers, follow this link to download the Maclean’s iPad app in the iTunes Store. You can also find it at Next Issue Canada.

Remember the legacy of Robin Williams with a free digital edition of our special commemorative issue, available for download on your iPad. For subscribers, check the newsstand in your Maclean’s app. For new readers, follow this link to download the Maclean’s iPad app in the iTunes Store. You can also find it at Next Issue Canada.