The Nashville insurgency: Inside country’s revolution

Meet the new breed of indie country outlaws who are rescuing the genre from a plague of tailgates and halter tops

Share

The most damning indictment of country music in recent memory came not from a latte-sipping rock critic, or a twang-hating guardian of taste, but from one of Music City’s own. Greg Todd was an aspiring Nashville songwriter two years ago when he noticed distinct similarities between the songs getting airplay on mainstream country radio—distinct, even in a genre known for artistic conformity. To test his suspicion, Todd used an audio software program to mash-up MP3 files of six top singles from the previous few years—smash hits by such C&W mainstays as Luke Bryan, Blake Shelton and Cole Swindell.

The resulting mash-up could have passed for a “bro-country” standard on Anywhere, America-FM. All six tunes shared the same key, the same pop-inspired tempo, the same inane lyrical themes celebrating beer, pickups and girls in Daisy Duke shorts. Todd had strung shards of the songs into a single track that built toward a mind-boggling coda: At the end, all six files played simultaneously, in near-perfect synchronicity.

As the mash-up’s YouTube count soared toward seven figures, a ripple of horror coursed through Nashville. For years, country chart-toppers have been plying the same lucrative formula—“a tight, mid-tempo backbeat,” as Todd described it, “a quick, two-verse set-up and, bam, the power chorus to bring it all home.” But the creative implications were enough to wake the most cynical record exec in a cold sweat. Had their industry been reduced to a single song?

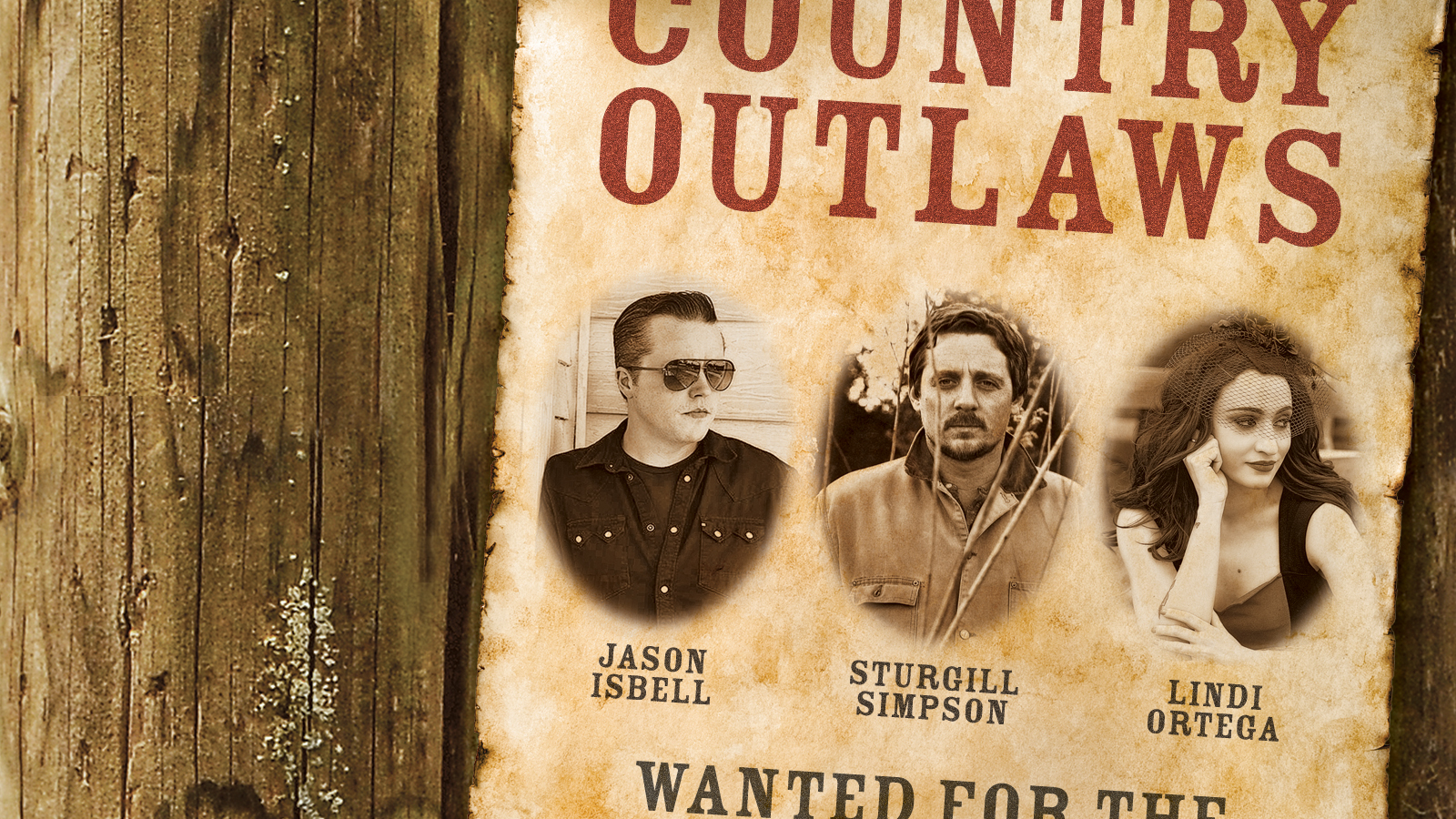

Mercifully, no. Even as critics as authoritative as Merle Haggard declare country moribund, a strain of daring, visceral music is bringing new life to the genre—rescuing it, some hope, from its plague of tailgates and halter tops. Albums by independent singer-songwriters like Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson and Chris Stapleton have surged in sales over the past 12 months, treating listeners to deliciously unprocessed sounds, along with lyrics that treat country’s timeless themes of sorrow, frustration and self-medication with jarring frankness. The producer of all three acts, a laid-back Nashvillian named Dave Cobb, has been nominated for three Grammy Awards this year, including Producer of the Year. Stapleton picked up three nods.

They’ve done all this with virtually no support from mainstream radio, where only Stapleton’s single Nobody to Blame is getting steady rotation. Instead, the insurgents have elbowed their way onto the charts thanks to digital downloads, streaming services and alternative platforms like podcasts, reclaiming discerning fans who’d long ago given up on the genre.

Their success has inevitably led to comparisons with the “outlaw” musicians of the 1970s, who abandoned Nashville for musical frontiers like Austin, Tex., leaving behind a staid scene defined by “countrypolitan” stars like Lynn Anderson and Charley Pride. But whereas Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson drew on rock ’n’ roll influences, thrusting country into uncharted territory, the new rebels are tugging the genre back to its outlaw past, when it turned lonesome, ornery and mean. Far from fleeing Music City, they’re reclaiming it, colonizing its gritty east end and haunting its back-alley honky tonks.

“Nashville really matters right now,” Cobb told Maclean’s in an interview last week. “This is the only place where art meets commerce, where there are record labels and people playing in their garages. It’s just electric and on fire, and I really want to capture what’s going on here right now.”

The city and its music have seen these revivals before. Even before Waylon and Willie lit out for Texas, Buck Owens had forgone Nashville for Bakersfield, Calif., where his rock-inspired guitar sound was not regarded as musical treason. The injection of danger the outlaws provided to country lasted until the early 1980s, when pop-crossover acts like Janie Fricke—backed by strings; light on twang—were all the rage. Then, at the end of the decade, hat-and-boot traditionalists like George Strait and Patty Loveless stormed onto the scene, restoring Nashville’s sense of self. Owens, it could be argued, returned in the guise of Dwight Yoakam.

A similar renaissance appears to be under way now. “Like Waylon Jennings, only more so,” is how Garrison Keillor described Simpson’s voice after inviting the Kentuckian to play on NPR’s Prairie Home Companion. Simpson’s drug-friendly lyrics (“Tell me how you make illegal / Something that we all make in our brains?”) certainly recall the outlaws’ appreciation for pills and smoke. But they’re part of a broader attempt by the new artists to document their reality with unflinching honesty—much as Kris Kristofferson and Townes Van Zandt did during the Outlaw heyday.

None writes with less inhibition than Isbell, a recovering alcoholic and former member of the Drive-By Truckers, whose songs plumb the canyons of a troubled mind. His 2013 single Elephant, for instance, is told from the viewpoint of a man watching the woman he loves waste away from terminal cancer. The two spend a night drinking away their sorrows, and he puts her to bed in a separate room. “If I f–ked her before she got sick / I’d never hear the end of it / She don’t have the spirit for that now,” he thinks.

Such candour, it goes without saying, is not a ticket to FM stardom. “Jason Isbell gets no play on mainstream country radio—zero,” says Kyle Coroneos, whose blog Saving Country Music has given many of the new artists much-needed exposure. Yet somehow he’s found an audience. Isbell’s latest record, Something More Than Free, rose to No. 1 last summer during its first week on Billboard’s country album chart, and has remained in the top 30 ever since. He’s spent the past year playing to jammed concert halls, with a sold-out date set for Toronto later this month.

Stapleton’s rise was even quicker, bringing a mainstream acceptance the bearded Alabamian didn’t think possible. His new album Traveller debuted in May at No. 2 and then faded. But on Nov. 4, he appeared alongside Justin Timberlake at the Country Music Association Awards, where the pair performed Stapleton’s bluesy take on the George Jones classic Tennessee Whiskey. That week, Stapleton sold 52,000 albums or album equivalents, mostly online, and Traveller shot to No. 1 on the Billboard 200.

That an artist with as much hair on his face, and front porch in his music, could eclipse pop sensations like Selena Gomez speaks to how profoundly digital music formats are changing the industry landscape. Downloads and online streaming accounted for 63 per cent of country music consumption last year, the latter making up nearly a third of that share. Those services, including Spotify and Google Play Music, have skewed listenership because they don’t share FM radio’s simple mission to draw the widest possible audience within a genre.

Instead, their curators create playlists from the broadest possible array of genres and styles—often featuring lesser-known independent musicians who’ve uploaded their work directly to the platform. “Our service is particularly good at exposing artists to new listeners who otherwise wouldn’t have found them,” says Peter Asbill, who became global streaming lead for Google Play Music last year, after the web giant took over his upstart streaming service, Songza. “In other words, we help artists cross audiences, or find new audiences.” In doing so, they’ve reduced the dependency of Nashville record labels on radio, disrupting a symbiosis that has lasted the better part of a century. The effect has been to empower maverick producers, whose music now has a fighting chance of reaching buyers’ ears.

Like most of the artists in his orbit, Dave Cobb does not see himself as country’s saviour. Born in Savannah, Ga., Cobb had played in a rock band and was living Los Angeles when the migration of artists to Nashville caught his attention. He’d just produced a raw, hard-driving album for Shooter Jennings, son of Waylon, and found himself in a circle of dissident country songwriters. Some called their music Americana—a catch-all that includes elements of blues, country, folk or rock. Some called it alt-country. To Cobb, the label didn’t matter so much as the sound he’d grown up with, and suddenly realized he missed. In 2011, he followed his friends to Tennessee.

Related: A Q&A with David Cobb

Cobb operates less by method than by ear, assembling groups of musicians in the studio he installed in his West Nashville home, pouncing on sounds that arise from experimentation. “Most of these artists had not had record deals, or only small ones,” he tells Maclean’s. “So there was no pressure, nobody watching the clock, no one wondering when the next record was coming out.” Lindi Ortega, a singer-songwriter from Toronto who has recorded two albums with Cobb, says he excels at identifying artists’ strengths. While working on her most recent, Faded Gloryville, Cobb surprised her by challenging her to play a guitar-picking track herself. “Other producers would hire session players to do stuff like that,” Ortega says. “But he’s got this way of making you feel great at what you do—that you as an artist have something of value to give.”

The emphasis on performance produces a kind of sonic purity Cobb believes fans are longing for. He sees the same thirst in resurgent demand for old, vinyl records, whose “humanity” he seeks to replicate. “People playing together in a single room. People playing together without overdubbing, so mistakes are left in,” says Cobb, who also produced the latest album by Edmonton’s Corb Lund. “Whether it was old Motown, Stax, Muscle Shoals or George Jones, it was humans in the room together, without technology. You hear the errors, you hear the heart, you hear the soul.”

Still, the revolution is far from over. Ortega laments that artists receive a minuscule cut of proceeds when their songs get played on streaming services—“I might see half a cent from one play.” So commercial radio, with its relatively generous royalties, remains relevant from a songwriters’ perspective, raising the incentive for them to produce more bro country.

The hope now is that radio formats will loosen, given that independent artists have gathered almost as much market share as the commodified acts, and record companies are starting to embrace them. Both Simpson and Stapleton are now signed to major labels. Last week, Stapleton’s Nobody to Blame was slowly climbing Billboard’s country airplay chart, sitting at No. 20. “I still call these artists independent because they have control over their music,” says Coroneos, the Saving Country Music blogger, from his home in Austin. “But that’s starting to happen within the infrastructure of mainstream country music.”

Whether that will force Coroneos to change the name of his website remains to be seen. Country music, he observes wryly, is “a copycat business” that will no sooner renew itself than slide back into conformity. For now though, it’s nice to see some of its best forging ahead together, each one singing a different tune.