The real challenges of reviving a Louis Riel opera

The Canadian Opera Company has reworked a problematic opera about the story of Louis Riel. Does it succeed, all the same?

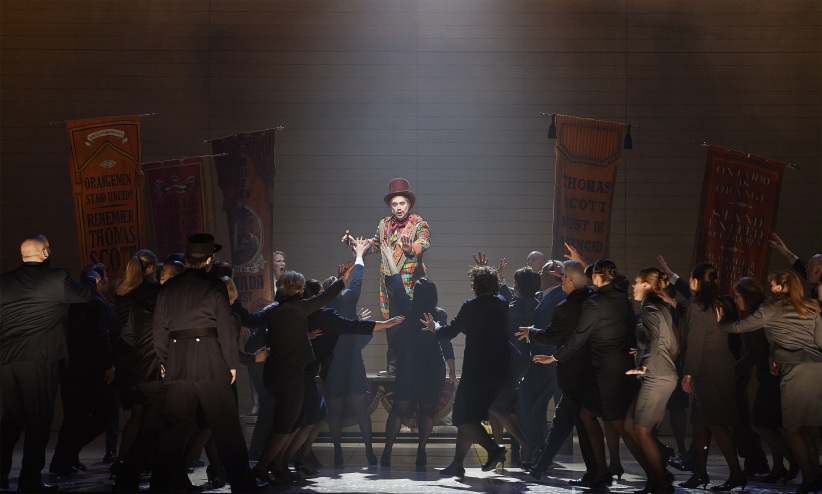

Russell Braun as Louis Riel in the Canadian Opera Company’s new production of Louis Riel, 2017. Conductor Johannes Debus, director Peter Hinton, set designer Michael Gianfrancesco, costume designer Gillian Gallow, lighting designer Bonnie Beecher, and choreographer Santee Smith. (Sophie I’Anson/COC)

Share

In 1967, the Canadian Opera Company premiered a brave new work commissioned for Canada’s Centennial: Louis Riel, by Harry Somers (music) and Mavor Moore (libretto, assisted by Jacques Languirand), refused to condemn or sanctify its controversial protagonist. The public and critics embraced it at the time, so a COC revival this month should be a no-brainer. But the situation, like Riel’s story, is complicated.

The CBC’s version of the original production, shot on a soundstage in 1969, features white actors wearing redface; it depicts Métis characters carousing drunkenly (the libretto calls for “a covey of tarts” and refers, in the stage directions, to “half-breeds”); it includes an aria that has been lifted, in part, from a traditional song by the Nisga’a in B.C., and given dubiously translated lyrics in Cree without any acknowledgment of the original. Although the opera has plenty to admire, including its savviness about political machinations, its avoidance of musical cliché, and its upending of the convention whereby characters burst into song when they want to express their true feelings—here, singing is a tool of persuasion—it has significant blind spots. True to its time, it portrays key moments in the conflict between the Métis leader Riel and Canada’s John A. Macdonald-led federal government, from 1870 in Red River to 1885 in Saskatchewan, in terms of East versus West, and English versus French. In the original, says Peter Hinton, who directs the COC’s new revival, “Riel’s indigeneity is just a side point.”

His production, which opens April 20 at Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre, takes on this issue directly—which hasn’t been a straightforward task. “I can’t call up Harry Somers and go, ‘Could you write a longer Batoche section? Could you put some [Métis] fiddle music in the show, please?’ ” he says. “You have to take this fixed thing and try to crack it open a little bit.” But having famously directed an all-Indigenous, Algonquin-themed production of King Lear in 2012 at the National Arts Centre, Hinton has shepherded similar transformations, and is uncommonly open to other people’s ideas and voices.

Where the original opera is mainly in English and French, Hinton—along with assistant director Estelle Shook, who’s Métis and, coincidentally, the great-great-granddaughter of Thomas McKay, a Cree Scottish lawyer who testified against Riel when he was put on trial in 1885—asked Cree and Michif speakers to translate some lines spoken by Indigenous characters into these languages. The cringeworthy scene with the “tarts” is now a joyous dance celebrating the buffalo hunt the Métis are singing about, choreographed by Mohawk dancer Santee Smith. As for the uncredited aria, “Kuyas,” it has been retranslated and is being made the subject of a COC-hosted consultation with members of Indigenous communities about what to do when such appropriation occurs. And Hinton and Shook have made the essential decision to cast Indigenous performers—the first, indeed, to be playing Indigenous characters on the COC’s mainstage since the Four Seasons Centre was opened in 2006.

“The first six minutes of the opera is all Indigenous people onstage, moving in silence, looking at the audience,” says Hinton. “It’s a very interesting tension.”

These performers comprise the Land Assembly, a group of 15 Indigenous people (out of a cast of 99), some of them non-actors. They serve as what Hinton calls a “physical chorus,” at times participating in the action as extras (while breaking the frame in contemporary dress), at others looking on from the sidelines, or standing amongst the characters to bear witness. Their presence adds a fluidity to the staging and a symbolic weight to the action.

Affiliated with the Land Assembly is a character called The Activist, played by Cole Alvis, who is of Métis, English, and Irish descent. After delivering an Indigenous land acknowledgment at the opera’s outset—the only words added to the work—The Activist is speechless thereafter, as is the Land Assembly. By contrast, the singing chorus, made up of non-Indigenous performers, offers commentary—including anti-Riel chants that bring to mind Trump supporters’ mantra, “Lock her up!”—while wearing business attire and often sitting on benches up above the action as if they were the jury in a courtroom.

“There’s a huge imbalance when it comes to who’s speaking, who’s controlling the narrative, who’s running the show,” says Alvis. “We represent ourselves”—i.e., Indigenous people—“responding, silently. I hope the audience [will] wonder what we’re thinking and what we would say if we were speaking.”

Is it difficult to remain silent?

Alvis pauses. “I wouldn’t say that I feel frustrated; I think there’s some merit in watching how people navigate challenging situations. I hope that we represent those alternative ways of mitigating oppression.”

Métis performer Jani Lauzon plays the introduced role of The Storyteller—an amalgam of minor roles that finds her singing folk-derived music (in contrast to the score’s overall atonal intensity). Often, she stands in the foreground as if she were the conscience of the politicians doing most of the talking and singing. “As a contemporary Métis woman on the stage, presenting the story to the audience,” she says, “I am both in it and outside of it simultaneously. I can jump into the history, and I can comment as an outsider.”

The Land Assembly, with whom the Storyteller often walks, bridges the past and the present and gives the production a historical resonance. Without it, the opera might feel sterile—a reproduction of a 1960s version of the 1870s and ‘80s.

It also keeps us focused on just who is performing. “The education system implies that we are no longer,” says Lauzon. “By having us present on the stage, it’s clear that we are still very much alive.” Ojibwe soprano Joanna Burt, who plays Sara Riel, Louis’s sister, agrees: “It’s about broken promises to Indigenous people [both] back in 1885 and now, because promises are still being broken. I want people to realize that this isn’t just a thing of the past. We still have problems—the Kinder Morgan [Trans Mountain] pipeline, for instance.”

“This project is so important right now because it’s essentially about activism,” says assistant director Shook. “How do we be active politically, and who defines what is subversive? Who gets to decide whether you categorize [something] as a rebellion or a resistance? Those are really important distinctions in this age when you can get arrested for protesting.”

The production coincides, of course, with the Canada 150 initiative, whose celebratory thrust has been soundly critiqued by some Indigenous activists and groups. “I grew up, like a lot of people of my generation, being told Canadian history was boring,” says Hinton, 54. “Working on this piece has suggested to me that maybe this ‘history is boring’ thing has a very conscious will in it: a will for us to not look at the atrocities of our past, and to say, ‘We’re peacekeeping, we’re welcoming’—to put a positive spin. The history of Louis Riel is a very provocative challenge to us.”

And the revival of an opera about Riel written by two white men is provocative too, especially with a white director at the helm. When he was asked to take on the role, Hinton says, “I had to really weigh out my involvement meant, what I could contribute, and what I needed to be really mindful of in terms of seeking out collaborators to work with.”

The spirit of collaboration has clearly energized the production, while creating, as Shook notes, “a lot of high tension” when it comes to artistic direction.

Hinton recalls a “big moment” when the designer had asked that the Land Assembly wear contemporary clothes with bare feet. “She liked this surprising contrast. We thought it was good, and then some of the performers were emotionally [saying]: ‘No no no, we have to have shoes. Why do the white characters get to wear shoes?’” In the end, most of the performers chose to wear shoes. “I find those moments very interesting when the same action occurs and it’s perceived and felt very differently,” Hinton says. “It’s very dramatic, and that happens every day in Canada.”

As a director, Hinton is no tyrant. After all, he says, the opera presents a time and place when “the government is faulty; the authority coming in is questionable, and there’s rightful power and justice in resisting that enforcement.” And nowadays? “I want to live in a Canada where we can disagree.”

The opera itself seethes with fraught drama—every scene involving Riel (played by Toronto baritone Russell Braun) involves (literal) soul-searching, as he seeks guidance from God and angrily justifies his decisions to everyone around him. Combined with Somers’s often astringent score—“You’re not going to leave The Four Seasons humming a song from Riel!” says Hinton—it makes for uneasy listening and viewing. John A. Macdonald, played by Stratford baritone James Westman, may be portrayed as a duplicitous, bibulous pragmatist, but he offers some light relief—even as the Land Assembly focuses attention on the devastating impact of his decisions.

“I am hoping that people are moved by the story,” says Lauzon, “and that that opening of the heart may spur them to look at our collective history a little differently.”

And for Burt—who’s forthright about her experience being “treated like s–t for being a poor, Indigenous girl” as an opera student—she hopes her presence in a lead role on the mainstage will be inspirational. “People tend to think that opera is unattainable art that you can’t do unless you’re a rich, white person. If I can get where I’m at, then anybody can.”

Inevitably, some aspects of the production continue to invite skepticism; Alvis cites the use of the Nisga’a song, which the COC discovered, apparently too late, had been appropriated. Nonetheless, Alvis shares a similar hope. “I choose to participate with my eye on potential—that the COC is sending press releases about stolen songs, that land acknowledgments are happening, that the production team understand what smudging [lighting of traditional medicine] is and how to accommodate it. This is 101. These are not big gains, but I celebrate them because of what they may mean for Indigenous artists—to be in leadership roles, creating new work here, and wherever they choose to be.”

CLARIFICATION: A previous version of this post described consultations over the aria “Kuyas” as being led by the COC. The consultations were facilitated and hosted by the COC, but were led by a Queen’s University professor.