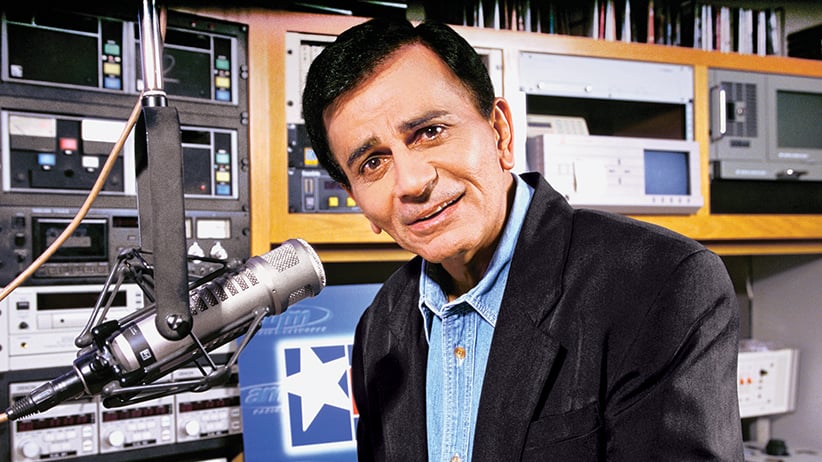

Tracing Casey Kasem’s sad, strange final days

Mark Lepage tracks the gothic tale of a radio icon, the private investigator assigned to follow him, and the widow postponing the DJ’s final rest

Kim Kulish/Corbis

Share

This past summer, while the online tabloids were puzzling over the whereabouts of recently deceased radio legend Casey Kasem, his body turned up in the unlikeliest of spots: a Montreal funeral home. The local press could find no Québécois connection to Kasem, which led everyone to wonder: why? And how?

By then, the drawn-out ugliness surrounding Kasem’s last days—released in the wee hours from the California nursing home where he’d spent much of the past year, ill with advanced Parkinson’s and dementia; driven across state lines to Las Vegas; flown to Washington state, whereabouts and condition then unknown—had already been TMZ fodder for months. Where was he? Why had his wife removed him from a home, only to transport him around the country in his fragile state? And then, what happened when, five weeks later, Kasem died? The bizarre circumstances around all of it seemed deeply inappropriate, given the nature of the man’s life. The answer to those questions is the peculiarly American horror story of: a beloved radio icon; his widow, a former TV actress; his grieving, angry daughter; a private detective; a disappearing body and a ghoulish post-mortem cross-continental tour.

Casey Kasem was, through the latter half of the 20th century, an iconic, if anodyne, presence in American culture: an announcer for Armed Forces Radio during his stint in the Korean war, a dance-hop DJ in the ’60s, and co-founder of the American Top 40 syndicated radio show in 1970. He played pop hits in the album-rock era, drawing listeners in with homespun biographies of the artists in the countdown to the No. 1 song. His catchphrase was characteristically Hallmark-card-like: “Keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars.” He voiced Shaggy in Scooby-Doo. A liberal, a vegan, a gentle guy.

But his last chapter is the weird finale in a story that saw years of animosity between his second wife, Jean, and the kids from his first marriage: daughters, Kerri and Julie, and son, Mike. Jean Kasem—you might remember her as Loretta Tortelli, the bubbleheaded blond wife of Carla’s ex-husband Nick in Cheers—seems to have had no relationship with her adult stepchildren, from the get-go. In past interviews, Kerri claimed the kids weren’t invited to the 1980 wedding, when Jean was then 24 years old and their father 47. It should be pointed out, on the flip side, that the Casey-Jean marriage was no fly-by-night affair: It lasted 34 years, until his death, a relationship that took him to age 82 and her to 57, and produced a daughter, Liberty Jean, now 23.

No one knows why Jean removed her husband from Berkeley East Convalescent Hospital in Santa Monica at 2 a.m. on May 7. Kerri, 42— a former UFC host, actress and current L.A. radio personality who broke into public life as an MTV Asia VJ—took the lead in voicing her family’s concerns to media. She alleged that Jean was hiding Casey from his friends and family. Kerri hired Logan Clarke, a private investigator in Huntington Beach, Calif., whose clients—including showbiz types—seek him out for tasks including finding and “extracting” kidnap victims, and “fugitive recovery.”

In a story with many outsized characters, Clarke is no exception. Renowned for his work against human trafficking, he’s a detective with 27 years experience who’s been cited as the kind of guy Bogie would play and Dashiell Hammett would write. In an interview, he notes that when Jean removed Casey from the Santa Monica convalescent home, Casey had a feeding tube surgically implanted in his stomach. “Her attorney told her a court order was coming down the next day, granting medical conservatorship to Kerri,” Clarke says. This is confirmed by a letter from the medical board to the Santa Monica Office of Criminal Investigations, which states that Jean came in and checked Casey out against medical advice, refusing to sign the requisite release documents. She also “disconnect[ed] his G-tube,” the letter notes, “which provided his only source of nutrition and hydration. She was informed of the risks of doing so and was told she was placing Mr. Kasem in great bodily harm or possible demise.”

From there, says Clarke, Jean loaded her husband into a separate SUV and had him driven from Santa Monica to Las Vegas, a four-hour drive. The PI is not shy about voicing his feelings about that decision. “This woman has access to $80 million and she doesn’t fly him there?” he asks incredulously. As has been widely reported, Jean would indeed then fly with her husband to Kitsap County in Washington state. Here, Clarke claims an ambulance driver, called to transport Kasem from the airport to a friend’s home, was so concerned about the possibility of elder abuse that he filed a protective-services complaint. An L.A. judge then overruled a May 12 judgment in favour of Jean and granted Kerri immediate medical conservatorship of her father.

Money was likely not among Jean Kasem’s motivations; she reportedly already had access to her husband’s fortune. Jean Kasem did not respond to numerous interview requests for this story by email and phone. In fact, she hasn’t spoken to media since the June 1 incident when Kerri, armed with the new ruling, picked up her father at the Washington house with an ambulance to take him to the hospital, only to have Jean hurl a package of raw hamburger toward her and reporters present and pronounce: “In the name of King David, I throw a piece of raw meat to you, to the dogs, to the dogs”—a scene reported with glee by the tabloids. Ambulance attendants did take Casey to a hospital in nearby Gig Harbor, where the feuding families could visit him, thanks to separate visitation times mandated by the judge.

In the midst of all this, Casey Kasem was dying, and did so on June 15, of sepsis. Jean had his body taken to a nearby funeral home, where he remained for a month until, in mid-July, Kerri obtained a restraining order to prevent Jean from having the body cremated and to request a second autopsy—but, by then, Casey Kasem was already at Urgel Bourgie funeral home in Montreal.

Maclean’s efforts to contact the Urgel Bourgie funeral home were unsuccessful. A secretary at the complex said the president, Yvan Rodrigue, was “the only person who could make a statement” on how and why, and even if, Casey’s body had arrived. But Rodrigue couldn’t be reached for comment.

The question, of course, is what connection did Jean even have with Montreal in the first place? Clarke claims to have an answer. “JP Gressy. Her boyfriend,” he says.

John Paul Gressy, a Montrealer, once tried to launch a jeans company called Dungarees U.S.A. in old Levi’s factories in San Francisco a decade ago. It flopped. He has since been linked romantically to Jean, with Clarke stating that the two had been seeing one another while Kasem was ailing; he says neighbours confirmed Gressy had been living with Jean in her Malibu condo for just over a year.

Meanwhile, back in Montreal, Kasem’s coffin was taken to Pierre Elliott Trudeau Airport on the weekend of Aug. 16, and flown to Oslo. Clarke obtained and released the Aug. 7 letter Jean Kasem wrote to Norwegian authorities. In it, she stated: “I would like for my husband of 35 years to rest in peace in Norway. He always said that Norway symbolizes peace and looks like heaven and I would like to respectfully fulfill his wishes.”

There is no public evidence that Casey, born in Detroit of Lebanese extraction, fancied Oslo, and Clarke says Jean “had to pay $2,600 plus change because they’re not residents and citizens of Norway.” However, in the letter, Jean Kasem claimed Norwegian heritage and said she planned to move to Norway by the end of the year. “Therefore,” she wrote, “I would also like to be near my husband’s resting place so my daughter and I could visit him often.”

Was all of this a final romantic gesture from a woman married to Casey Kasem for three decades of her life? What else could explain her behaviour? When asked what she thinks, Kerri Kasem barely suppresses a snort of derision. “I have no idea. Maybe if she was evaluated by a mental doctor . . . ”

Clarke alleges there is a darker motive. “Jean’s on the run,” he says. “There was an autopsy. We wanted more done and that’s why she’s carted him around.” On Sept. 29, the Oslo funeral home where his body was resting stated that it would not be burying Casey Kasem, having received a Kerri-organized petition with 20,000 names on it.

Something concrete may yet come of this. “We will find out where my dad is eventually buried when the law that I am working on passes,” Kerri says. That would be Visitation Bill AB2034, authored by California State Assemblyman Mike Gatto, who appeared with Kerri when it was introduced in June 2014. The bill would protect children from being denied access to a parent by a parent’s future spouse or child. “Jean Kasem would be court-ordered to tell us where our dad is,” she says.

Lost in all of this is the man himself. Casey Kasem was famous for a honeyed baritone and his genteel, avuncular presence on the airwaves for five decades. Among the pitiable catalogue of ailments that beset his final days was Lewy body dementia, which rendered him mute. And now, as his final rest is further postponed, one of America’s signature voices once again has no say in the matter.