Unpacking the real Alex Colville

He is iconic, yet misjudged. A magnificent new show unpacks a master of exquisite realism

Art Gallery of Ontario employees unload Colville’s “Study for Looking Down” in preparation for the museum’s new exhibit. August 8th, 2014.

Share

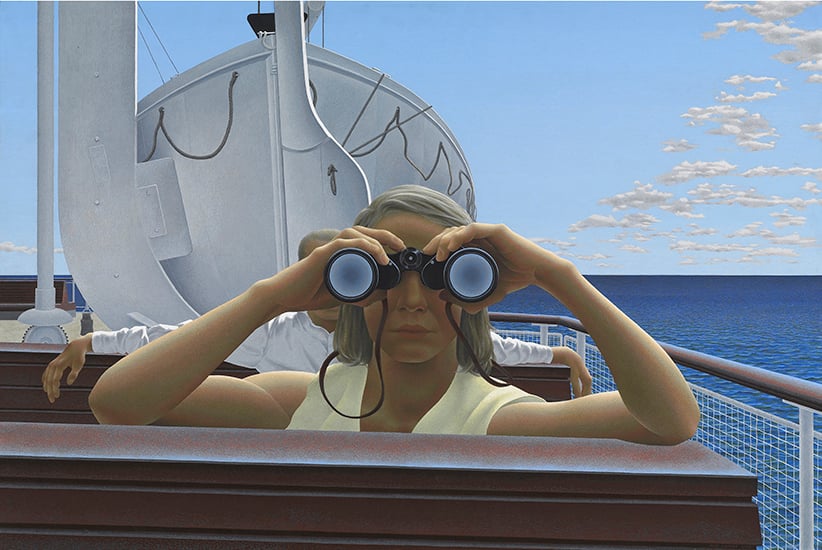

“The woman sees, I suppose, and the man does not,” Alex Colville once remarked of To Prince Edward Island, one of his most celebrated works. Like the painting itself—a woman on a ferry, her face hidden behind binoculars she directs at the viewer, she herself hiding the man behind her—the comment was typical of Colville, obscuring not only the intense thought and preparation that went into his works, but how constant a theme it represented. For an artist who painted so often and so starkly about seeing (which dogs, crows and some people, mostly women, can in his work) and not seeing (most people, especially men, can’t), Colville can be awfully hard himself for Canadians to rightly perceive.

Partly it’s the ubiquity of his best-known works, reproduced everywhere, from the iconic Horse and Train that adorns a Bruce Cockburn album cover to The Elm Tree at Horton Landing on the front jacket of a book of Alice Munro short stories to the coins that once jingled in our pockets (Colville designed a Centennial Year series for the mint). But primarily, suggests Andrew Hunter, curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario exhibition Alex Colville, opening in Toronto on Aug. 23, it’s the technically exquisite realism, falsely familiar yet hardly soothing, that can mislead.

Colville was a realist, the curator says, “because he knew that things can always go horribly wrong, that they were always on a fine balance. You can view Woman in a Bathtub in multiple ways, from loving intimate moment to something far worse.” Ann Kitz, 65, Colville’s youngest child and only daughter, says her father “was a pragmatist, and not inclined to think people were inherently good. He believed evil existed.”

A realist, in short, not because he painted representationally, but in part at least because he’d been to the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen as a young war artist, in May 1945, when its emaciated victims were still dying by the thousands. Last fall, months after Colville’s death at 92 in July 2013, when Hunter and Kitz were going through Colville’s studio cabinets, they found “a startling watercolour of bodies from Bergen-Belsen,” says Hunter. Colville had not sent it to the Canadian War Museum with his other army works, but had kept it, evidence of a lifelong habit of keeping bad experiences tucked away but close at hand.

The AGO’s magnificent show, accompanied by Hunter’s superbly written catalogue, will surely strip away any patina of ordinariness Colville might have in the consciousness of his countrymen. Containing more than 100 of his 150-odd paintings, along with dozens of drawings and sketches, it will be the most Colville in one place ever. And it will show him as an important modern artist, Hunter says, “how relevant he is to the contemporary conversation on image and image-making.”

There will be “pairings,” as the AGO calls them, with Wes Anderson, who restaged To PEI in his 2012 film Moonrise Kingdom, and with the Coen brothers, whose staging of Javier Bardem near the end of No Country for Old Men (2007) echoed Colville’s famously arresting self-portrait Target Pistol and Man. The four Colvilles featured on the walls of the resort hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s seminal 1980 horror film, The Shining, will be set off. There will be additional pieces by living artists to accompany Colville’s own, including a biographical comic by David Collier and works by Gu Xiong, who was an art student in China when the Canadian government sponsored a Colville exhibition there in 1984. “Gu went to see it,” Hunter recounts. “Then he took a copy of Horse and Train to his studio, like every other art student in China. ‘We used to say,’ Gu would tell me, ‘We were the horse and China was the train.’ Five years later, it was more they were the lone guy and China was the tank.”

National Gallery of Canada (no. 14954). © A.C.Fine Art Inc

Hunter thinks the Chinese government, like so many others, was fooled by Colville’s everyday subject matter. “They probably thought it was ‘safe,’ a variety of the sort of socialist realism they were used to. Classic Colville: always sneaking in under your first impressions.” Like the horse in Church and Horse (1964), the painting Hunter thinks is most illustrative of Colville’s mix of local core and outside eruption, of menace and order. “The church, from the 1860s, old and rundown, is still there, near Hastings, N.S., but any local will tell you that horse is definitely not from around here.” The charger, which looks like it’s about to destroy the tottering remains of the past, is the riderless horse from John F. Kennedy’s funeral, an event Colville watched attentively on TV.

It’s one of Hunter’s favourites, but the curator has a lot of those. There’s Woman with Terrier, one of The Shining four, which Colville once jokingly described as “my Madonna and Child; of course in my world the child is a dog.” Colville had “a peculiar idea of dogs,” Hunter adds. “They are sentient but incapable of evil—they can see. People and dogs in his art represent distracted and hyperaware capacity for evil and innocence. The woman’s face, unsurprisingly, is hidden by the terrier. “Colville’s averted faces implicate viewers in his works, make us feel like voyeurs. When someone in a Colville looks directly at the viewer,” Hunter continues, “it’s as though you have interrupted him or her, broken in on a private scene.” In Target Pistol and Man, the gun’s barrel is on the table, but the handle is still in the air: the man isn’t contemplating the weapon, he’s just dropped it.

Almost all this globally resonant subversion, including all the most iconic images, emanated from a quiet corner of Maritime Canada. There is one spectacular exception. Pacific—that disturbing painting of a man, his head cropped off, gazing out to sea in the background and a pistol lying on an otherwise bare table in the foreground—is “currently the most requested reproduction,” according to Hunter. It is also the one work Colville did in Santa Cruz, when he was a visiting artist at the University of California in 1967. “Even then,” the curator adds, “the table was brought with them from Wolfville,” the Nova Scotia town where the Colvilles lived from 1973, in his wife Rhoda’s family home.

There, as in Sackville, N.B., where he lived from 1946 to 1973 (teaching at Mount Allison Unversity until he quit to become a full-time artist in 1963), Colville lived a life as orderly as the surface of his paintings. “He was really good at balancing life and work,” recalls Kitz. “After exercise, bath and breakfast, he’d go upstairs and work until noon—his best hours were always eight to noon—six days a week, never on Sunday. He never pulled all-nighters, coming downstairs haggard at breakfast.” Colville’s oldest child, Graham, the only one born while Alex was still overseas, tells of meeting his father for the first time. “I was over a year old and we were both shy. I’m told his first words to me were, ‘Would you like an olive?’ My father was not a Norman Rockwell dad—he never went to hockey practice with me, none of that clichéd bonding. But we did have a lot of shared experiences, especialy with sailing. Rowing, actually—we were always getting becalmed in Minas Basin. There wasn’t much talking, but a lot of closeness.” Colville liked to make things, says Kitz, particularly of wood: his own frames and packing cases for his paintings, “and all my doll furniture.”

The surroundings of that tidily civilized life provided all the forms his astonishing body of art required—pets, farm animals, landscape, sea, boats, children and above all, his wife. Rhoda and Alex Colville were married for more than 70 years. She was muse and subject for his entire working life—there is a drawing of her as a teenager and she is in Woman and Clock, his last work, painted in 2010—and she appears in drawing after drawing, painting after painting, often naked. (As does he, several times, most notably with a naked Rhoda in Refrigerator.)

Colville used to display his finished works in the family home for a week or so before shipping them off. The maternal nudity meant nothing to the children—“that was our normal,” laughs Kitz—but, in a story Kitz suspects is growing in the telling, Rhoda had to coolly serve tea to the local Ladies Church Auxilliary under a large portrait of her naked in a tent. “My mother understood what my father did was fine art,” Kitz says, “but it still made her uncomfortable sometimes.”

It’s impossible to imagine Colville’s career, let alone his life, without Rhoda, his very ability to create seven decades of examining images of trust and vulnerability, so many with feelings of inchoate danger hanging over them. She died in late 2012, just half a year before her husband. During those last months, Colville, as he once told his son Graham, took Rhoda’s death as “a piece of information I put away in a secret place.”

[mlp_gallery ID= 421]