‘Kicking the Sky’ chronicles a bloody way to come of age

How the 1977 murder of a shoeshine boy transformed Toronto

Barrie Davis / The Globe and Mail / CP

Share

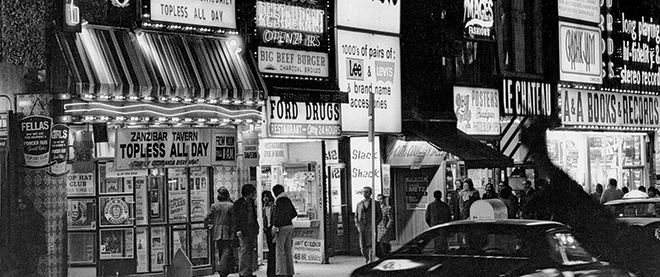

“It seemed like the person I was now was not the person I would’ve been if Emanuel Jaques had not been murdered,” says 11-year-old Antonio Rebelo, the protagonist of Anthony De Sa’s Kicking the Sky. His fictionalized version of his childhood self is not speaking for him, De Sa insists. Not in a personal sense, that is. But the brutal 1977 rape and murder of 12-year-old Emanuel—a shoeshine boy lured, by a promise of $35 for moving photo equipment, into an apartment above the Charlie’s Angels body-rub parlour on Toronto’s then notorious Yonge Street strip—was in fact a catalyst for wide-scale change in the look and feel of the city.

And much more than that within the poor and previously invisible Portuguese immigrant community that was home to Emanuel, Antonio and De Sa, 11 himself at the time. “ ‘Shoeshine Boy,’ one of the stories in my first book, had the murder as a kind of background,” says the writer about his Giller prize-nominated collection Barnacle Love. “But it brought such a response. So many people my age, not all of them Portuguese, could remember where they were, how they heard the news. Most wanted to talk to me about its legacy, cleaning up Yonge Street. There were so many other implications, though—for the way people thought of Toronto, for the gay community, for police and politicians—who looked out their windows and saw 15,000 angry Portuguese demonstrating. In my own life, like in Antonio’s, it was the first time our door was ever locked.”

Wandering with De Sa through the streets and back lanes of the writer’s childhood neighbourhood just west of downtown Toronto, he points out change and continuity. There are gentrified $800,000 homes nestling beside houses that look as though they need the neighbours’ support to keep upright, cousins met on one block and an uncle’s home passed on another, and the house De Sa lived in until he was 16. “Then we moved next door in the world’s fastest move,” he laughs, describing a human chain of extended family passing their possessions from hand to hand. “We didn’t need the bigger house any more. My father bought it because he knew he’d be putting up his relatives as they came over from the Azores. By then they had houses of their own.”

Antonio—impressionable and shocked to his core as the veil of adult secrecy unravels before his eyes—has his share of happy childhood memories, too. “He thinks, just like my friends and I thought,” says De Sa, “that he’s invincible, that nothing bad will happen to him. But just like us, Antonio sees how the crime has affected his parents, sees their fears and the frustration that they can’t be around because they were both working two jobs. We were latchkey kids and we revelled in it.”

The thematic arc of Kicking the Sky contrasts the dangers of a big city coming into its own—Antonio recalls how Toronto came to a halt to proudly watch a helicopter lower the CN Tower’s last component—with the dangers inside Antonio’s tight-knit ethnic community, from exhausted and abusive parents and free-roaming children. Some of those kids gather in groups and go gay bashing downtown, exacting what they see as revenge for Emanuel. “There was far more homophobia in the wake of the murder than we remember, or want to,” the writer says. “Few in the novel distinguish between pedophiles and homosexuals—and that was true in real life too, an atmosphere fed by some politicians and media figures. Don’t forget that the bathhouse raids, police arresting hundreds of gay men, came after.”

And some of the community’s children, again as much in reality as in De Sa’s novel, were hustling on the edge. “That’s a lot of money for a child in 1977, $35; even as a kid I knew Emanuel knew, or thought he knew, what he was getting into,” De Sa says. “And I knew my parents knew, but we never spoke of it.”

A coming-of-age story with a vengeance—not just an individual, but an entire community—Kicking the Sky also captures a small but enduring turn of the historical screw. Antonio was right, after all: after Emanuel Jaques, everything changed.