A Danish crime novel that breaks the rules of the murder mystery

Book review: The Murder of Halland, by Pia Juul

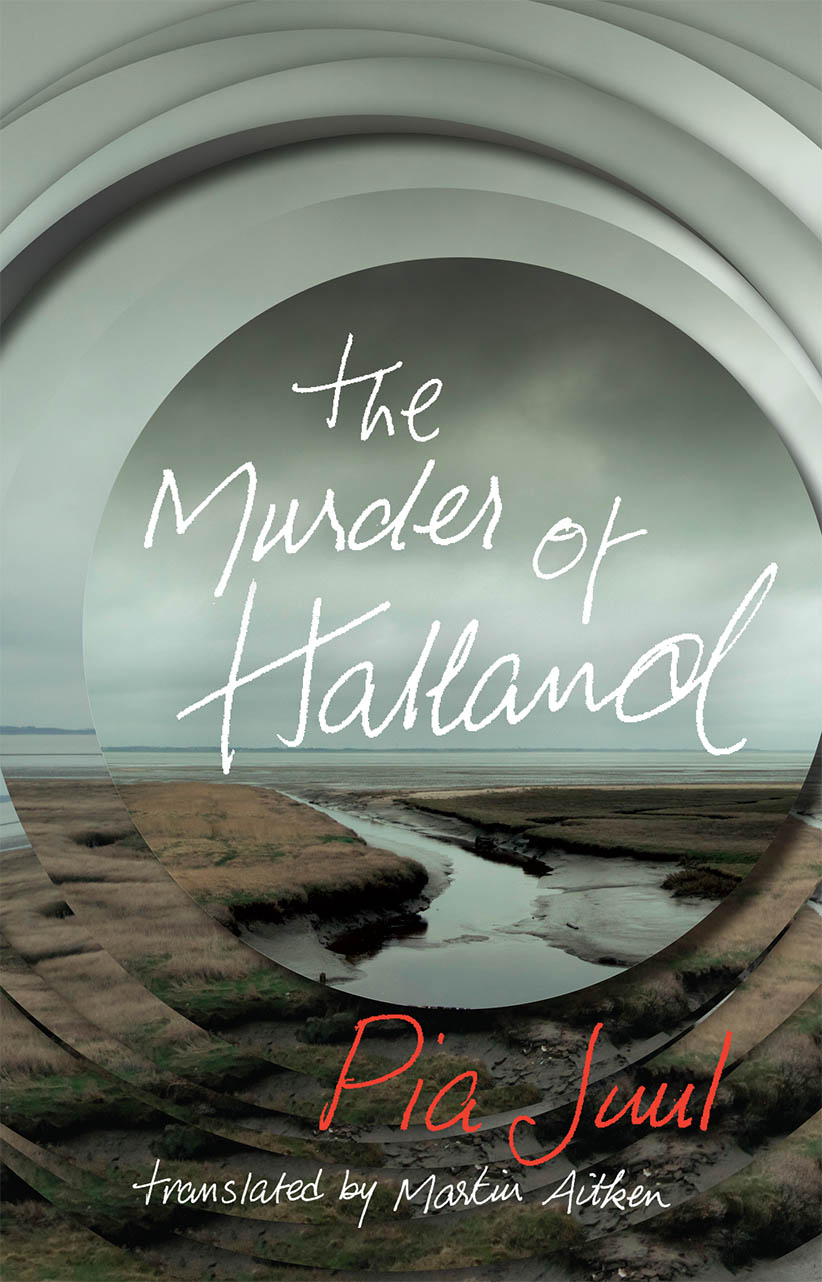

The Murder of Halland by Pia Juul. Translated by Martin Aitken.

Share

THE MURDER OF HALLAND

Pia Juul, translated by Martin Aitken

“Won’t be long” are the last words Bess says to her common-law husband. He goes up to bed in their house in a small town in Denmark; she spends the night engrossed in a piece she’s writing, and eventually collapses on the sofa in the living room. In the morning, he’s gone and her routine is interrupted by the doorbell. “Are you the wife of Halland Roe?” a man at the door asks. “I’m arresting you for the murder of your husband.” He isn’t a police officer, but rather, Bjorn, a school caretaker, attempting to make a citizen’s arrest. While Halland lay dying from a gunshot wound on the cobbles of the town square, he told Bjorn, “My wife has shot me.”

So begins The Murder of Halland, a book that may sound like a classic Nordic crime novel but displays a refreshing disregard for crime fiction’s norms. The detectives and their investigation are secondary. So is the question of Bess’s innocence. (The novel is told from her point of view, and her innocence is clear from the start.) Instead, the book probes the aftermath of violence, and death, from the spouse’s point of view: what happens when a husband vanishes into a morgue, leaving the detritus of lives abruptly changed.

Originally published in Denmark in 2009, where it won that nation’s top literary prize, Juul’s 147-page novella is a spare, elegant jewel. Every word is chosen with such care that Halland Roe is the only character worthy of a first and last name. Bess is just Bess, the detective is Funder, the next-door neighbour, Inger. The brief quotations that open each chapter merely hint at other stories, buried secrets. One has a famous fortune-teller saying: “I see you lead a double life. There’ll be an extra charge for that.”

While a handful of clues are carefully scattered through the book—Brandt, a neighbour and doctor, disappears halfway through the book—the clues are not the point. The focus really is Bess’s mourning process, which is irrational, at times even bizarre. It’s as if she’s compiled a list of how to act when a husband is murdered, then does the opposite. This isn’t a clue so much as a crystalline glimpse into the strange disconnection into which loss plunges us. At one point, Bess gets a visit from Pernille, the heavily pregnant “doe-eyed beauty” who was Halland’s niece and holder of one of his biggest secrets. Bess watches Pernille leave in the rear-view mirror. “Maybe she’d be hit by a car!” Bess thinks. “But no car hit her.”

Terse and enigmatic, this novel is a classic to be savoured again and again, perhaps with Halland’s favourite tipple: aquavit.