A history of the art world’s most notorious conmen

Book review: The chief investigator at a Boston museum dishes on the liars and cheats of the art world

Share

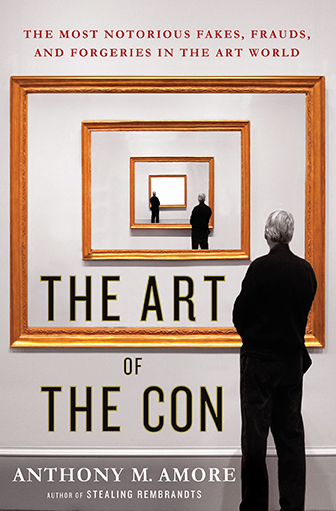

THE ART OF THE CON

Anthony M. Amore

Sticks-in-the-mud who think anyone can make modern art will find ammunition in this book: serial forgers, Amore writes, cleave to Impressionism and abstract expressionism because the old Masters’ technique is too hard to imitate. Nonetheless, New York’s notorious art criminal Ely Sakhai had a Rembrandt faked by his sweatshop of ill-paid forgers to be sold to a Japanese businessman whom he managed to bully into accepting it, despite the dissenting opinions of experts.

Sakhai’s is one of the more startling tales of chutzpah collected by Amore, chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, whose previous book was Stealing Rembrandts, about thefts of the Dutch Master’s work. Here, he collects stories of faked paintings, forged documents, unauthorized copies, and falsified histories—methods of duping, from the meticulous brushstroke to the inkjet printer. All hinge, he argues, on “an art lover’s desire to believe that he has made a great find and executed a great deal.” If a work’s stated provenance seems wildly improbable and exciting, so much the better. It seems there’s a sucker born every Manet, and even if a gallerist or buyer should realize he’s been taken, often the sums involved—and the possibility of selling the fake for even more money—can secure his complicity.

Amore makes a good investigator—he’s great at uncovering facts from court documents and narratives from interviews. His prose is matter-of-fact and the book’s structure a bit formulaic. But there’s a lot to be learned about the art world from this book: about the ridiculous proliferation of fakery, for instance, especially with unauthorized lithographs and giclées; about the ways fakes can be uncovered; and about the romantic ways forgers are viewed—some, after being outed, have had their own art shows and auctions.

This patina is tarnished by sellers like Sakhai, who threatened his Chinese employees with exposure of their illegal-immigrant status if they exposed him, and by replicators armed with moulds of sculptures; presumably 3D printing will pose new problems. Down the line, what happens to our cultural obsession with authenticity and history if we can no longer tell the original from the copy? What if we’re left to focus on the art itself?