A look back at Hogtown’s history to see how we got here

Book review: ‘Toronto: Biography of a City’

Share

(Library and Archives Canada/PA-171131)

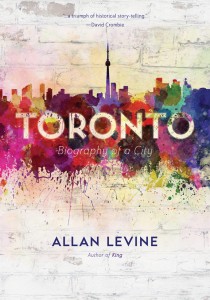

TORONTO: BIOGRAPHY OF A CITY

By Allan Levine

There are two overarching themes in Levine’s shrewd and lively account of two centuries of Toronto history. The first, never precisely spelled out, is that one of Canada’s great unifiers—a common loathing of Hogtown—is a peculiar form of self-hatred, given how quintessentially Canadian the city has been in its attitudes and development. The other can be summed up by “as it began, so it continues”: Toronto’s signature blend of mulish parochialism, both puritanical and entitlement-minded, and genuine openness to the outside world seems hard-wired. The city that required three closely fought referenda over seven years in the 1890s before the streetcars could run on Sundays is currently demanding an up-to-the-minute rapid-transit system that stops at every corner. Toronto’s saving grace—if that’s the right phrase—has always been the citizenry’s shared devotion to commerce: show us the money, and change will come. The same attitude that casually destroyed the city’s waterfront by handing it over to railways and highways has also been instrumental in allowing Toronto to adjust to massive changes in its very makeup with minimal trouble.

At least in recent years. Levine moves smartly through his account of Muddy York’s original elite, the Family Compact—in a section that reads, entertainingly for locals, like a portrayal of animated street names: Joseph Bloor meets William Jarvis meets John Strachan—to get to the city’s new powerbrokers of the 1840s. They were mostly Irish Protestant businessmen, organized within the Orange Order, who were in control in time to face Toronto’s first real influx of outsiders, Irish Catholic famine refugees. Between 1839 and 1864 there were 29 riots—either political or, more frequently, sectarian—involving the Orange lodges, a number that doesn’t include the semi-comical Circus Riot of 1855. (After visiting American circus clowns beat up some local Orangemen in a brothel, the city fire brigade—like the police, a bastion of the order—pulled down the Big Top while a mob burned the circus wagons.)

Toronto’s established communities have always displayed what Levine calls “a righteous mood” toward newcomers. Even as religious divisions slowly dissipated, the city’s black community (a presence from its earliest days) and later waves of immigrants, starting with Jews and Italians, faced the same dual response: welcomed for their labour (and, lately, their capital), disdained for their otherness. It parallels residents’ demand for village-level services in a “world-class” city, part of Toronto’s endless dogfight about whether it should aim to be a global urban centre or a gigantic small town. For all the crack-smoking novelty of the Rob Ford years, Levine concludes, they are just another chapter.