A memoir that grapples with loss, one book at a time

Peter Orner’s book of essays explores the loss of his father, his failed marriage and the immovable, sometimes tragic, force of plot

Share

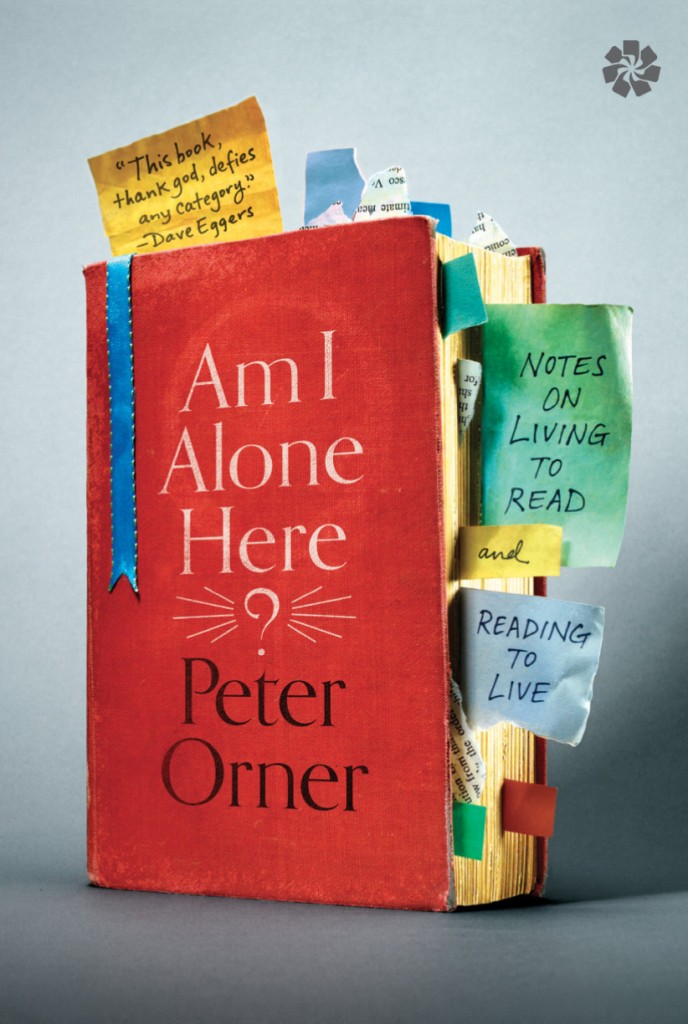

AM I ALONE HERE?

AM I ALONE HERE?

Peter Orner

Peter Orner killed off his father. This was in the novel, Love and Shame and Love (2011), in which the fictional paterfamilias has a heart attack on the floor of a Brooks Brothers on Michigan Avenue in Chicago. When the actual elder Orner died three years later, the son was left wordless. He couldn’t write fiction. For the author of two novels and two collections of stories, this amounted to an intense double grief. “His sudden non-existence left me with a blank I had no idea how to fill,” Orner writes. “Since it is my job to obliterate blankness with words, I felt adrift.” So, the writer takes a seat on the other side of literature—as a reader—to sort himself out.

Am I Alone Here? is a collection of essays subtitled Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live. Indeed, Orner is always reading, always reminiscing. He reads Woolf in a canoe in Minnesota, Welty on an island off the coast of South Carolina, Gallant at his kitchen table in Bolinas, Calif. He knows that stories, both his own and others’, allow him to approach the ineffable from oblique angles. “Remembering a book,” he writes, “is like remembering a person.”

What emerges is a subterranean autobiography. Orner broaches his rocky relationship with his father with the help of Bernard Malamud’s story “My Son the Murderer.” A tender farewell between two lovers at a train station in Heinrich Boll’s “Parting” gives him room to examine his conflicted feelings over his failed first marriage. His second wife and young daughter appear hardly at all in these pages, though their overarching importance is certainly implicit in his moving essay on Moby Dick. Orner, whose best fiction focuses on barely disguised members of his own family, here dissects the sad moment when Starbuck, the first mate, pleads with Ahab to allow the crew to return home to their wives and children. “Of course,” Orner writes, “if they’d given up the hunt, we wouldn’t have a tragedy, and without a tragedy we wouldn’t have the book. Plot’s got to do what plot’s got to do. But maybe this is why I’ve always been so wary of it. It forces characters to do something, anything, when all they should be doing is going home.”