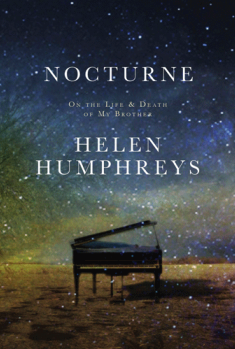

A novelist on the death of her brother

Our book review of Helen Humphreys’s ‘Nocturne’

Share

Humphreys has always been a minimalist. None of her first six novels topped 200 pages; they couldn’t go on much further, she once said, because they caught “the emotional lives of my characters at a high pitch.” The intensity of their situations meant that both Humphreys and her readers could “only stay there for a while—that kind of terrain is not good to linger in.” With this taut elegy for her brother, Humphreys is back in that familiar terrain again, and with a similar result. However bleakly intense and grief-racked the landscape of memory is for the author, for a reader Nocturne is simply beautiful, still and moving in even measure, definitely terrain to linger in.

Humphreys has always been a minimalist. None of her first six novels topped 200 pages; they couldn’t go on much further, she once said, because they caught “the emotional lives of my characters at a high pitch.” The intensity of their situations meant that both Humphreys and her readers could “only stay there for a while—that kind of terrain is not good to linger in.” With this taut elegy for her brother, Humphreys is back in that familiar terrain again, and with a similar result. However bleakly intense and grief-racked the landscape of memory is for the author, for a reader Nocturne is simply beautiful, still and moving in even measure, definitely terrain to linger in.

Martin Humphrey was a gifted musician diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in late July of 2009. By Dec. 3 he was dead, aged 45. The shock, the speed and the helplessness tore through his older sister. She began to write of her loss and its effects, in part for Martin, in part for their younger sibling, Cathy, but mostly because that’s what writers do: impose structure, craft a story, claim memory.

There are lovely moments throughout, all infused with the heightened awareness brought by knowledge of his death. There’s one of Martin’s concerts, a lunchtime event for a bunch of sandwich-eating, white-coat-wearing scientists at the National Physical Laboratories in England, which must have happened when Helen visited him there. She can’t recall, but no matter. “There was a lot of overlap to our lives in those days. We were made of each other then.”

But what makes Nocturne powerful art, paradoxically enough, is its capture of art’s powerlessness before physical reality. If there is a theme that runs right through, it’s a cold-eyed realization that, much as we’d want it otherwise, the only presence we can count on in our lives is our own.

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary