A real-life Hollywood murder mystery, breathlessly told

Book review: William J. Mann’s ‘Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood’

Share

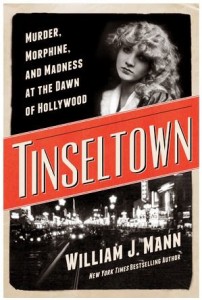

TINSELTOWN: MURDER, MORPHINE AND MADNESS AT THE DAWN OF HOLLYWOOD

TINSELTOWN: MURDER, MORPHINE AND MADNESS AT THE DAWN OF HOLLYWOOD

William J. Mann

Even among hard-core cineastes, William Desmond Taylor is likely an obscure figure. An actor of little esteem, who appeared in 27 silent films, he achieved greater success as a director, helming 59 features in just nine years. Taylor’s career ended abruptly on Feb. 1, 1922, when he was shot dead inside his apartment in L.A.’s tony Westlake Park district. His murder, more than his films, has earned him a small, steady ripple of notoriety, and it serves as the linchpin for Mann’s rambling examination of the debauchery, deceptions, delusions and desperation that fuelled Tinseltown in the hopped-up years before movies could talk.

Some 4,800 km east in New York, then filmdom’s financial base, the industry’s first moguls, Adolph Zukor and Marcus Loew, battled for supremacy. Both fretted over the looming threat of anti-trust legislation and cries for censorship of the morally and sexually loose storylines that peppered Hollywood’s early output—cries exacerbated by such scandals as the sensationalized manslaughter trial of comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, the grisly, drug-related demise of leading lady Olive Thomas and Taylor’s headline-grabbing murder.

Four women, variously linked to Taylor, provide Mann this book’s foundation. Mabel Normand, a major silent star, was Taylor’s closest confidante. Margaret “Gibby” Gibson was his frequent co-star, but, as breakthrough success eluded her, she turned to prostitution, blackmail and extortion. Mary Miles Minter progressed from child to teen star, shining for a time near as brightly as Mary Pickford. Only 19 at the time of Taylor’s death, she insisted they’d shared a grand passion and planned to wed. Finally, there was Charlotte Shelby, Minter’s overbearing, money-grubbing mother, determined to let nothing—including a debonair director—derail her daughter’s lucrative career.

It’s a lot to weave together; and the connections and suppositions Mann makes can often feel tenuous. Yet, as a narrative, it works, largely because it unfolds precisely like a silent film: a breathless storytelling style, emotional excess, the occasional pratfall, and colourful characters—heroes, villains, damsels in distress—literally out of central casting. As for Taylor, at first presented as the epitome of aristocratic gentility, his closet proved crowded with skeletons, including a checkered past under a different name, an abandoned wife and daughter and, once he was ensconced in Hollywood, a male lover hidden in plain sight on the same lot where he worked. Did any, perhaps all, of these revelations contribute to his death at age 49? You’ll have to wait till the final reel to find out.