A reluctant travel writer’s haunting essays

Marius Kociejowski’s writing captures his subjects indelibly

No caption

Share

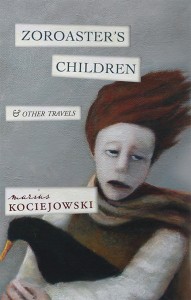

ZOROASTER’S CHILDREN

Marius Kociejowski

It’s not quite ironic that one of the most evocative travel writers to emerge in the last decade feels “vaguely embarrassed” to be described as a travel writer. Kociejowksi is vaguely embarrassed often, whether when asked to name influences on his poetry (because that amounts to counting himself as the peer of those poets), or even, although he does not say so explicitly, when acknowledging his Canadian birth and upbringing, because his own feeling of displacement is nothing compared to the traumas of the exiles he writes about.

Kociejowski has run an antiquarian bookshop in London for decades. He’s not a real travel writer, he asserts, not one of those who have survived snakebite or mastered “the more remote dialects of already impenetrable languages.” But here he protests too much, and in a bygone style. (An antiquarian bookseller reads a lot of 19th-century accounts of exotic journeys.) Kociejowski’s travels consist of encountering people, not places, and, in this kind of travel writing, he may well be peerless. His recollection of his entirely conversational interaction with a Moroccan prostitute in Marseilles is witty (business wasn’t good for either book or sex seller: “We had both been spiked by the video trade”) and simply beautiful. Disturbed, after an interval of years, by his inability to fully remember her features, Kociejowski asks a question that lays bare his deepest interests and showcases his remarkable prose. “What is it about the human face that it should be the most memorable thing in existence and yet its atoms are the quickest to disperse?”

All the essays feature a laser-like focus on individuals and a relative indifference to their surroundings. In the title story, which, naturally, unfolds in Iran, Kociejowski meets a young book-lover in a bookshop in drought-stricken Isfahan. Farhad invites him home to see his English-language library, which turns out to be a relative handful of paperbacks. But the writer recognizes them as a collection so difficult to gather in contemporary Iran, “that I, who dealt in rare books, had never seen any quite so rare as these.” Eventually, Farhad explains why he needs the “escape route” of modernist English writing: A few years before, he had received 84 lashes for having had a sip of gin. “The river is empty,” he tells Kociejowski, “and so, too, is the soul of this country.” In city after city—Prague, Moscow, Toronto—Kociejowski does the same thing: encounters people, pays extraordinary attention to them, and captures them indelibly.