A sideshow of an Appalachian novel

Book review: ‘A Hanging at Cinder Bottom’ is Mark Twain meets ‘Ocean’s Eleven’

Share

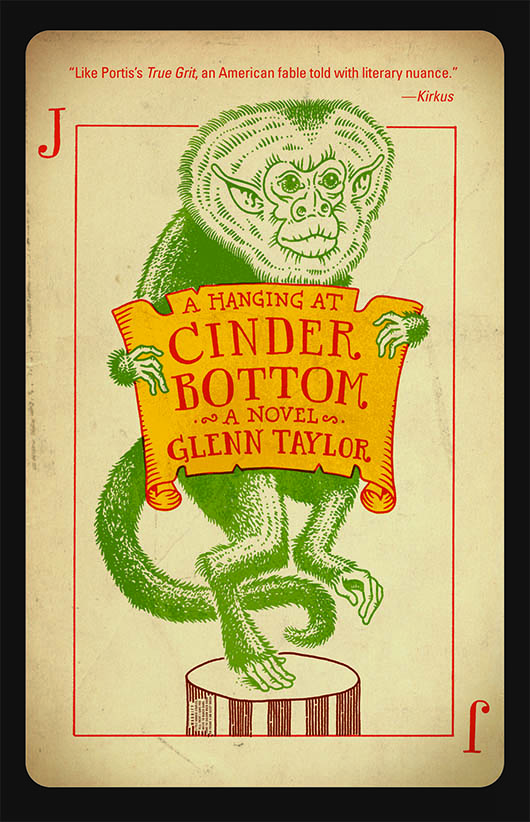

A HANGING AT CINDER BOTTOM

Glenn Taylor

With this book, West Virginia’s Glenn Taylor lets off a riot of literary fireworks. He produces a visual, olfactory, and auditory spectacular (as one of his fondly drawn grifter characters might proclaim). Consider just a fraction of the novel’s bursting-at-the-seams inventory: horse manure, saloon sharks, uncorked liquor, houses of ill fame, “the meanest woman there ever was,” pungent flophouses, a half-lemon diaphragm, farting dogs, a “scabied cat,” L’homme Péter (stage performer extraordinaire, with an internal, one-of-a-kind wind instrument), feral police, cut-barrel shotguns, elaborate cons, crooked games of chance, assumed names, opium dens, holy rollers, bunions, and tricks with mirrors.

Mostly set in a rowdy, drunken Appalachian boomtown named Keystone in 1910, Hanging opens with impressive comic bravado. Cocksure 30-year-old Abe Baach, possessing “a smile that could sell used snuff,” is a notoriously successful gambler and confidence man who has crossed unforgiving but corrupt lawmen. And with Goldie Toothman, his beautiful girlfriend, he’s scheduled to hang—in Cinder Bottom, the town’s red-light district—as a crowd of 3,000 gathers to gawk at the novelty. Far above, meanwhile, the approach of Halley’s Comet has the nation quaking with thoughts of imminent apocalypse.

Explaining how this couple landed in jail and what’s going to happen to them on the following August morning gives Taylor ample chance to build a crazy plot that suggests Mark Twain by way of Ocean’s Eleven. Flashing back to 1903, 1897, and 1877, he artfully recounts a complicated tale of aspirations, setbacks and retribution in a dizzying land of opportunity that’s lawless, feisty, murderous, and kindhearted in equal parts. If the complex story pieces occasionally overshadow characterization, pay no heed. Taylor’s “unruly work of fiction,” as he calls it, is no sober history. “The people want a big show,” Abe declares on the night before his expected death, and with a bounty of colourful details, Taylor wholly agrees.