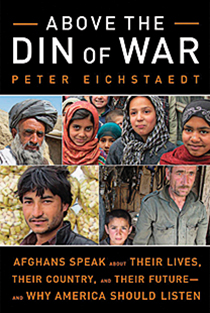

Above The Din Of War: Afghans Speak About Their Lives, Their Country, And Their Future—And Why America Should Listen

Book by Peter Eichstaedt

Share

Zahra, a young woman from Herat province in Afghanistan, was betrothed to an older man when she was 14, assaulted and nearly raped while walking home alone, shunned by her family for the supposed crime, and then stabbed and thrown into a well by her brother, who thought murdering her would cleanse the family of the dishonour she had brought them.

Zahra, a young woman from Herat province in Afghanistan, was betrothed to an older man when she was 14, assaulted and nearly raped while walking home alone, shunned by her family for the supposed crime, and then stabbed and thrown into a well by her brother, who thought murdering her would cleanse the family of the dishonour she had brought them.

Zahra, who somehow survived the ordeal, is one of dozens of mostly ordinary Afghans whose stories are recounted in these pages. And as a collection of such stories, it is a worthwhile book. Eichstaedt travelled widely and spoke to everyone from music shop owners to politicians and Taliban. This took time and diligence. But Eichstaedt doesn’t add much to their voices.

The book lacks a unifying narrative. Characters emerge, say their bit, and then disappear. Eichstaedt’s observations feel tacked on—as does his suggestion, in the final pages, that America’s best exit plan involves a negotiated settlement with all of Afghanistan’s neighbours. He muses about partitioning the country into semi-autonomous regions along ethnic lines, but not in detail.

Eichstaedt’s analysis of suicide bombing—“a desperate act of protest against a foreign way of life rapidly being adopted by an entire generation”—is silly, and is contradicted by moving testimony he obtains from young boys who were groomed by mullahs to kill. His assertion that “little or nothing has been done to improve basic aspects of Afghan society” is flatly untrue.

There remain revealing snapshots. Eichstaedt’s portrait of Bamiyan contrasts archeologists digging into Afghanistan’s Buddhist heritage with poor families living in caves dug out of the same cliffs where the Taliban once blew up centuries-old statues carved there. He probes Afghanistan’s great mineral potential and asks why China, which has not provided a soldier to the war, stands to earn billions from it. There is room for more depth here. Eichstaedt skims the surface and moves on.