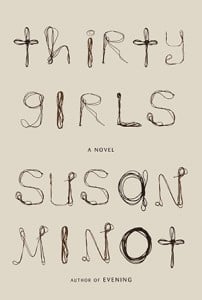

An eerily timed novel on school girl abductions

Maclean’s reviews Thirty Girls by Susan Minot

ca. 1996, Uganda — In October 1996, 30 girls were abducted from Saint Mary’s College by the Lord’s Resistance Army in northern Uganda. | Location: Aboke, Uganda. — Image by © Liba Taylor/CORBIS

Share

In 1996, rebels belonging to Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) kidnapped a group of students from a Catholic girls school in Uganda. The region was rife at that time with similar abductions of children, but this event stood out for the response of the school’s headmistress, who followed the rebels into the bush and requested the return of her girls. A fictionalized version of the incident serves as the introduction to Minot’s eerily timely novel, and features the rebels’ captain tracing numbers into the dirt—first 109 (the number of girls he will return) and then 30 (the number he will keep). He insists that the nun write down the names of the girls to be left behind.

From there the novel splits into parallel narratives. Sixteen-year-old Esther Akello, one of the 30, has escaped the LRA after a year and a half, and is now living in a rehabilitation centre for former child captives. Though physically safe, Esther is haunted by the deaths of other children in the rebel camps and part of her thinks she ought to join them. Meanwhile, Jane Wood, a fortyish journalist from the States, has come to Africa to write about the LRA abductees and also to blunt the pain of rejection by her drug-addicted ex-husband and his subsequent death by overdose. Jane becomes absorbed into a privileged and bohemian expat community, where she meets Harry, 17 years her junior and the antidote to her misery.

Each storyline is gripping in a very different way. Through Esther, the reader is confronted with the bizarre and sadistic habits of the rebels, and how they systematically broke children through rape, starvation and forcing them to kill. With Jane, a nuanced romance unravels, allowing a rare study of the anxieties that often accompany new relationships—now he loves her, now he doesn’t. The reader has an uneasy feeling—wishing, in one moment, to return to Jane’s drama and the relief it offers from the horrors of Esther’s and in the next, to stay with Esther, whose ordeal is so much graver and whose resilience so extraordinary—all the time wondering whether the two arcs belong together in the same book. Just when it seems they may never intersect, at least not in any meaningful way, Minot weaves them together to stunning effect.