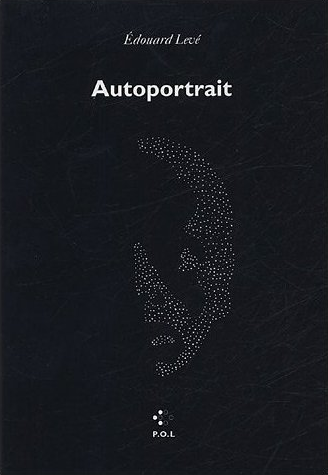

‘Autoportrait’: a memoir, Edouard Levé-style

The late French author’s penultimate book, newly translated, makes for compulsive reading

Share

We live in the age of memoir. If you eat, pray or love, chances are there’s a story you can sell. The publishing landscape is littered with non-fiction tales powered by that reliable fictional device – plot. But is this a proper reflection of reality? The way we experience the world is much more fragmented, more crammed with idle and mundane thoughts that constantly interrupt our generally plotless lives.

We live in the age of memoir. If you eat, pray or love, chances are there’s a story you can sell. The publishing landscape is littered with non-fiction tales powered by that reliable fictional device – plot. But is this a proper reflection of reality? The way we experience the world is much more fragmented, more crammed with idle and mundane thoughts that constantly interrupt our generally plotless lives.

Nobody understood this better than the late French writer Edouard Levé. In Autoportrait, originally published in France in 2005 and recently translated by Paris Review editor Lorin Stein, Levé bluntly acknowledges this fact. In a single book-length paragraph, Levé lays himself bare with 1,500 highly personal, yet completely non-sequential declarations.

Phobias, admissions, curiosities: the randomness not only mimics the way our minds work, but also makes for pure, compulsive reading. A single page can careen from the metaphysical (“I wonder whether the landscape is shaped by the road, or the road by the landscape”) to the political (“I vote for the Green party even though they rarely put forward a candidate I like”) to the sexual (“I do not foresee making love with an animal”).

Levé’s dry, direct tone can verge on the aphoristic (“Names draw me to places, bodies draw me to people”) or just plain odd (“I think the big toe is doomed to disappear”). No detail is too small (“I do not like bananas”) nor too quotidian (“I love the unpredictability of blue jeans: how, after you wash them, they shrink, age, fade”). These are the meanderings that make up a life.

Levé, a critical darling in France, was a strident conceptual artist. The rigourously formal approach of his prose was also evident in his photography. The pictures in Pornographie (2002) reduce brazen to bland by depicting fully-clothed people in static sexual poses, while Série Amérique (2006) collects snaps of small United States towns that are notable for their more exotic namesakes: Baghdad, Rome, Rio.

But it is in his writing that Levé was able to push his love of conceit to its ultimate degree. His last book, Suicide, is written to an old friend who killed himself two decades earlier. Suicide, termed a novel, presumably due to the attribution of his friend’s thoughts that Levé couldn’t possibly have known, is nonetheless kin to Autoportrait. Both are unflinchingly personal, and their unadorned sentences are deadpan in tone.

They differ, however, in point of view. Suicide is told in the second person (“You used to believe in written things regardless of whether they were true or false”). The use of “You” makes the book read like a love letter to a dear dead friend, but the second person address can also seem like an invocation of the self. This is a slippery “You” that helps the reader sidestep an awful truth: Levé hanged himself ten days after handing in the manuscript for Suicide.

It’s always dangerous to interpret fiction as biography, but the sensational nature of Levé’s suicide invites some contemplation: is it so unimaginable that such a thoroughly conceptual writer would plot out Suicide and suicide?

Perhaps. But if he did, then there’s a twist that even the author couldn’t have envisioned. In France, Autoportrait came out first and Suicide, two years later in 2007; in North America, the order was reversed. We read the suicide note first, the self-depiction second.

This quirk of publishing gives Levé a beatific glow as his obsessive attention to detail gains beautiful weight. He observes and records what he will eventually destroy. Despite this morbid truth, Levé has given us a fully realized life.