How Anonymous itself could be hacked

Gabriella Coleman’s meticulously researched account of the hacker group that escapes definition

LONDON, GREATER LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM – 2013/11/05: A demonstration organized by the Anonymous group has been held in Trafalgar Square to Westminster to protest against the austerity measures adopted by the government. Andrea Baldo/Getty Images

Share

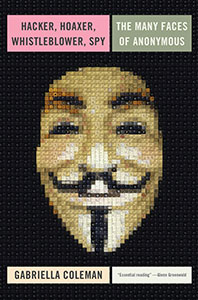

HACKER, HOAXER, WHISTLEBLOWER, SPY: THE MANY FACES OF ANONYMOUS

Gabriella Coleman

Anonymous is a faceless Borg-like monolith whose main goal is righting the wrongs of bullies—governmental and other. Or it’s a jellyfish adrift in the online sea, stinging whatever crosses it. It’s righteous and nihilist. It’s troll-led hate magnified, a terrorist in a Guy Fawkes mask. Many have tried and failed to shoehorn Anonymous into such descriptions. In this meticulously researched, eminently readable work documenting the online cabal/collective/gong show, Gabriella Coleman explains why: It’s all and none of the above—a cipher that’s so successful in confounding governments and spy agencies, precisely because it escapes definition.

A cultural anthropologist and professor at McGill University, Coleman first hung around Anonymous chat forums, gaining their trust. She then spent years as a privileged lurker, interviewing several members in the flesh. She traces the group’s rise in the early 2000s, from the meme-generating cacophony known as 4Chan, indulging in “Lulz” (pranks) on unsuspecting victims. Pointed in the wrong direction, this instinct led to reprehensible online acts, including the leaking of personal information of people. Yet change the target—a phone company that shares its customer info with the U.S. government, say—and the story takes on a Robin Hood-like narrative.

Anonymous’s first serious target, the Church of Scientology, reflects both the group’s self-righteousness and sense of humour. As a religion, it hardly has a monopoly on secrecy and abuse, yet the church provoked Anonymous’s ire by trying to block the publishing of an embarrassing video of its most famous member, Tom Cruise. The ensuing online attack was a PR nightmare for the church, from which, one could argue, it hasn’t yet woken.

The group has since either sparked or aided some of the highest-profile online campaigns the world has seen. Its members aided in the toppling of the Tunisian government and of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and helped to expose the lengths to which the U.S. government spies on its own citizens—all with a hearty dose of Lulz. “[W]hen you combine sociopaths with pissed-off altruists, get the f–k out of the way,” one hacker says.

Yet Coleman, ultimately, shows how Anonymous itself could be hacked. “Sabu” is a gifted hacker and a member of Lulzsec, an Anonymous subgroup known for its dastardly hack on Sony, AOL and the U.S. Senate, among others. A hero to the most jaded of Anonymous souls, Sabu eventually turned, and was responsible for eight prominent hacker arrests. Anonymous ultimately fell prey to Sabu’s online charisma. For a faceless group, it’s a surprisingly human failure.