The original Siamese twins

What conjoined twins Chang and Eng reveal about race, slavery and 19th-century America

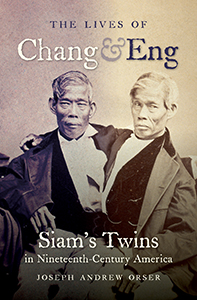

circa 1865: The most famous Siamese twins, Chang and Eng Bunker (1811 – 1874), after whom the rare condition is named. Born in Siam (modern Thailand), they married two sisters and had nine children each, eventually dying on the same day. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Share

THE LIVES OF CHANG AND ENG: SIAM’S TWINS IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

Joseph Andrew Orser

In the late 1820s, two brothers, conjoined by a mysterious band of flesh, set sail from Siam for America with a contract to be exhibited for a set period before returning home. Almost half a century later they died, American citizens, former slave owners, supporters of the Confederacy, married to a pair of white sisters and with their place in history confirmed as the eponymous Siamese twins. In between they were objects of fascination, examined by medical experts and viewed by thousands as they criss-crossed the American continent and the 19th century.

As his introduction makes clear, Orser sees Chang and Eng Bunker and their “monstrosity” as a prism through which to “interrogate” the American monstrosities of the time: race, slavery, miscegenation, and “sectionalism in a grand union.” He sets out to examine the twins in light of a burgeoning American Orientalism. His textual dissection—of newspaper accounts, promotional pamphlets, family letters and diaries—is thorough and unrelenting. The analysis returns again and again to uncovering the way race and race relations in the U.S. served to echo and amplify the physical deformity of the twins.

This textual parsing can exhaust the reader. Orser spends so much time ensuring the twins are placed in the context of a contemporary liberal academic framework that he fails to ever place Chang and Eng on the page. Even a small amount of context about 19th-century circuses and freak shows would have brought the world of Chang and Eng to greater life. The criticism reaches bottom when Orser reads Mark Twain’s Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins, a sketch that repeats an oft-told joke that lists the ages of the twins as “respectively 51 and 53.” Orser sees this as a way for Twain to align himself with his fellow Anglo-Americans. Twain was probably only trying to align himself with a laugh.

In Orser’s quest to humanize Chang and Eng, he seems unwilling to confront the negative reality that people are curious about lusus naturae. In one way or another—whether attending the circus or interrogating the “otherness” of the twins in a modern context—everyone takes a peek. We don’t have monstrosity exhibitions anymore; we have a liberal academic consensus. No matter how far we’ve come, the twins remain unknown, unknowable, and endlessly intriguing.