Book review: The rebirth of the great American song

Ben Yagoda, a gifted raconteur with a keen ability to deconstruct pop-cultural watersheds, is among the minority that insists the songbook never died

Share

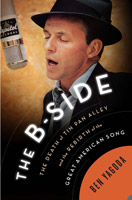

THE B-SIDE: THE DEATH OF TIN PAN ALLEY AND THE REBIRTH OF THE GREAT AMERICAN SONG

THE B-SIDE: THE DEATH OF TIN PAN ALLEY AND THE REBIRTH OF THE GREAT AMERICAN SONG

Ben Yagoda

Pretty much everyone agrees that the Great American Songbook began in the 1920s when masters like Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and Jerome Kern entered the fray. The end date is harder to pin down. Most observers sound the death knell around 1950. Others argue, quite fairly, that next-generation craftsmen like Frank Loesser and Richard Rodgers (plus the still-active Porter and Berlin) continued to produce sterling material into the ’60s. Then there’s a growing minority that insists the songbook never died, it has simply evolved. Ben Yagoda, a gifted raconteur with a keen ability to deconstruct pop-cultural watersheds, numbers among this uncircumscribed group.

Yagoda opens with a detailed history of the songbook (a mélange of Broadway, Hollywood and Tin Pan Alley tunes of enduring quality, generally recognized as “standards”) and its foremost practitioners—mostly male, mostly white and predominantly Jewish—as it progressed from the Roaring Twenties, accelerated through the Big Band Era, then stalled during the postwar years. So delightful is his anecdote-filled style that it’s easy to forgive his habit of diving into rabbit holes, overly dwelling on trivial details and minor figures.

Yagoda’s primary focus is on the pre-Elvis 1950s, when the music landscape rapidly deteriorated. Gimmicky novelty tunes were all the rage. Hits like Patti Page’s How Much Is That Doggie In the Window and Rosemary Clooney’s Come On-A My House topped the charts. At the centre of this sticky morass stood Mitch Miller, creative kingpin for first Mercury Records and then the mighty Columbia label. Frank Sinatra, among the few who managed to rise above such melodic mediocrity, affectionately referred to him as “that creep.” Certainly, per H.L. Mencken’s adage, Miller never went broke underestimating the taste of the American public.

In the Miller era, Berlin, Mercer, Rogers and their ilk remained active, particularly on Broadway and in Hollywood, but they became increasingly peripheral figures in a world they’d once dominated. Rock music’s ascendancy sealed their fate. (Though their work did, and does, continue to thrive within the jazz milieu.) But, Yagoda argues in the too-brief closing chapters, not all hope was lost. A fresh and very different assortment of songwriters, including Paul Simon, Carole King, Burt Bacharach, Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen—plus, from offshore, Len- non and McCartney—ushered in a new wave of equally durable gems. As he concludes, circa 1968, “The final page had turned on one songbook. Another was just starting to be written.”