Book review: The struggling sculptor

The hero of this graphic novel is struggling in New York when he meets a female angel in knee socks and Death, who bears a bargain

Share

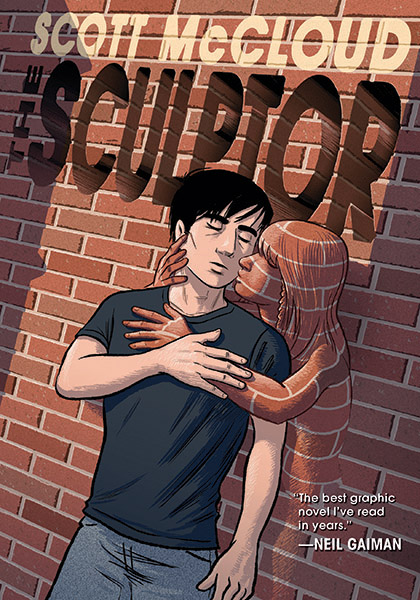

THE SCULPTOR

Scott McCloud

The promotional blurb for The Sculptor announces that this 490-page graphic novel is “the long-awaited magnum opus” of Scott McCloud. One supposes that in spite of McCloud’s Eisner Award and four Harveys, this must be so. The author is the leading theorist of the form—his immortal Understanding Comics was followed by Reinventing Comics and Making Comics—and he has produced a lot of experimental material for the web, as well as sitting in on serial superhero comics for short periods. But this is the big printed book McCloud fans really must have been waiting for.

The expectations created by a life of comics criticism and philosophizing are pretty hard to meet. The good news is that a generation of comics fans knows McCloud’s approach. (Maybe it is a couple of generations, now, at that.) McCloud is not an autistic genius draftsman of the R. Crumb calibre, nor is he a Joe Sacco type using reportage comics to battle injustice. He is what you might call “post-ironic”—the sort of fellow who, well, gets born “McLeod” and changes the spelling. He likes puns, science-fictiony gimmicks, and old-fashioned love stories. Even his bad-guy characters usually mean well.

The Sculptor is ostensibly about a sculptor, though McCloud does not disguise that he is talking about art in general, and a little about himself. The theme is that of Yeats’s “Choice”: pursuing “perfection of the life, or of the work.” In the early pages, our hero, struggling in an unfriendly New York, meets with two supernatural characters: Death, who comes bearing the sort of bargain that all good yarns require, and a cute female angel in knee socks, who descends from above with timely reassurance. Only one of the two is the real deal, metaphysically, but perhaps I shouldn’t say which. (Reviews of graphic novels are often annoyingly spoiler-ridden, owing to the necessity of showing off the art.)

As I say, McCloud is not afraid of gimmicks. But there are some serious ideas at play here: Yeats’s dilemma is genuine.The committed artist “must refuse/ A heavenly mansion, raging in the dark.” McCloud doesn’t have to solve the old artist’s problem of how to portray a really great Beethoven-class artist without being one: his sculpting protagonist is a portrait of someone perhaps much like McCloud—a perceptive middle talent with a sentimental streak and a weakness for both fantasy and fanservice. For all his gimmickry, however, McCloud does not quite go for the ordinary Hollywood ending.