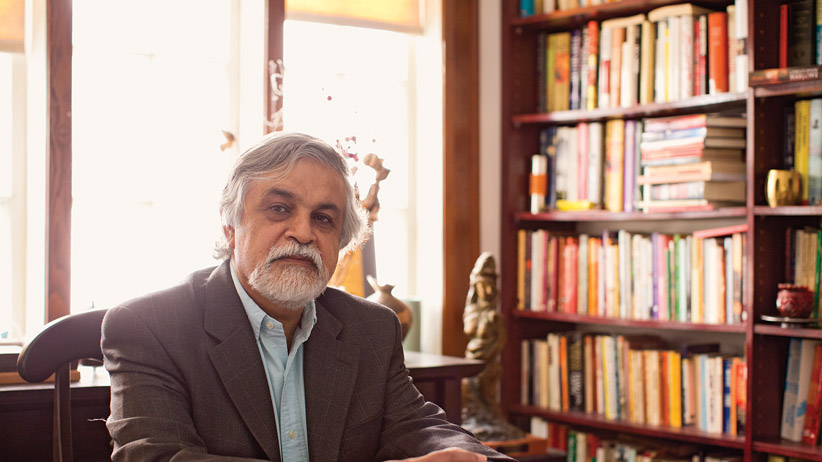

RBC Taylor Prize nominees: M.G. Vassanji, bound by East Africa’s call

Drawing on his sense of ‘mad belonging,’ M.G. Vassanji crafted an insider’s account of his place of birth

Share

Born in Kenya and raised in Tanzania, M.G. Vassanji is one of Canada’s most eminent writers. The first to win the Giller fiction prize twice, Vassanji also captured a Governor-General’s non-fiction award, and his new travel memoir of his East African homeland, And Home Was Kariakoo, is nominated for the RBC Taylor Prize. Vassanji has always been fascinated by what he calls “in-between” lives. “It’s not just what I write,” he says, “it’s what I am.” It’s the modern condition—“you could be from Newfoundland and now live in Toronto,” as Vassanji does. But Africa is a special case, he adds, partly because the in-between-ness of Asian Africans like him stretches over three continents, and partly “because I feel very strongly the world doesn’t hear enough from Africans. We talk about horrible conditions there and we give aid, but we don’t allow Africans at the cultural table.” That’s why Vassanji returned there for his new book, to craft an insider account of Africa’s rich and complex reality.

Here, as part of a series on the RBC Taylor Prize nominees, an exclusive excerpt of Vassanji’s book, And Home Was Kariakoo:

Down below, out the airplane porthole, lay the vast unconquered landscape of Africa—so different from the parcelled geometry of Europe which I had crossed over or the grey, highway-girded northeastern United States where I had made my home for the time being. The red earth and green scrubland, a few huts, a solitary figure wending its way on a trail to somewhere, perhaps carrying water, all under a cool morning sun that would in no time replenish its fires and begin to bake the earth. It must have been the arid north of Kenya, south of Somalia, down there below me, but it didn’t matter, the familiarity was unquestionable and it filled me with a huge emotion. This was my country. This was East Africa and I was returning home.

I was 21, it was only 16 months since I had gone away, but that was a long time then. Mine was the overwhelming emotion of someone who had feared he might not see home again. The people, the places; the music, the language: everything that was suffused into my pores and my very being, now crowded out by new challenges and pushed back into memory. That feeling about my African home would never change over the years and decades that followed, during which I would go to many places, including Canada, which gave me a home, and my Indian ancestral homeland, which partially claimed me back.

Many from my generation left during those heady 1960s and ’70s of the last century, soon after independence. Most went away to the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, and some have returned for visits, but few that I know with that intensity of emotional reclamation. Of mad belonging.

Modern aesthetic—I mean the Western one—prefers ironic detachment, a stony turning away from the emotion, a haughty look askance at anything that might give joy or sadness—seeing the inevitable winter behind the summer, the motive behind the charm, the spent passion, the bitter aftertaste. Does climate have anything to do with this? Those of us from the south—where fruits and vegetables actually rot and smell, and death is real, not irony—sometimes fear what the winters might be doing to us. I see my feelings about my place of birth to be mixed—obviously, growing older demands that—but disappointment does not poison the joy or the attachment.

Perhaps I judge unfairly this “Western” aesthetic. It is novelists, of whatever country and culture, who in some sense never leave home, who keep returning to it—despite that old cliché. Why this need to return? My answer is this: There is simply too much of life unexplored that, at a distance and prompted by nostalgia, yes, and the clarity of observed youth, yields precious narrative and self-knowledge.

The question arises: Is the return of the Asian African different from that of an African African? The answer is yes, if only because for the former, the ancestral South Asian homeland is a reality that looms closer today than it did on the streets of Dar es Salaam and Nairobi; the links to it are more realized. The returning African African comes with a global black consciousness. There is that unavoidable pulling away, then. And yet I’ve kept returning to this African homeland, and at each arrival there is that unmistakable tug at the insides, the same instinct to draw in deep from the air. The smoky coolness outside Nairobi airport at night, the salty humidity of Dar at the same time. The exclamations, the echoes of spoken Swahili.

Excerpted from And Home Was Kariakoo Copyright © 2014 M.G. Vassanji. Permission granted by Doubleday Canada. All rights reserved.