Blind bobsledder Steven Holcomb pens unflinching memoir

Holcomb hid his blindness from his family and colleagues before coming clean and winning gold

Share

Piloting a bobsled is no simple task. Over 600 kilos of steel, fibreglass and human flesh hurtling down an icy chute, it can’t be steered in any conventional sense, and the brake is only useful once you’ve made it to the bottom of the hill. Learning how to guide one—as safely and as fast as possible—takes years of bruising practice. Although surprisingly, actually being able to see the track isn’t necessary for success.

Piloting a bobsled is no simple task. Over 600 kilos of steel, fibreglass and human flesh hurtling down an icy chute, it can’t be steered in any conventional sense, and the brake is only useful once you’ve made it to the bottom of the hill. Learning how to guide one—as safely and as fast as possible—takes years of bruising practice. Although surprisingly, actually being able to see the track isn’t necessary for success.

Holcomb was an up-and-coming driver for the U.S. bobsled team when he was diagnosed with keratoconus, a progressive thinning of the cornea that can ultimately lead to blindness. But told that it would be years before his eyesight failed, and fearful of the potential fallout for his Olympic dream, he declined to make his condition known. It turned out to be a poor decision. Holcomb’s vision deteriorated much more rapidly than predicted. Within a couple of years he couldn’t see across a room, let alone down a track. And when he was named to Team USA for the 2006 Turin Games, he only passed the vision test by memorizing the eye chart.

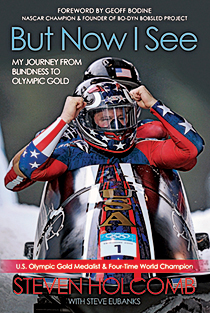

But Now I See, Holcomb’s memoir, traces the trajectory of his lie, and its devastating consequences. On the track he was almost invincible—winning the World Championship in both the 2-man and 4-man disciplines. But off it he was a mess, forced to withdraw from family, friends and colleagues lest he be found out. Depression set in, leading to a spectacular suicide attempt. It was only then that he found the courage to tell the truth.

What happened afterward has received plenty of coverage, particularly in the U.S. media. An experimental treatment led to a miracle recovery, and once his sight was restored, a gold medal in Vancouver. Holcomb’s tale has movie-of-the-week written all over it. But the book is admirably unflinching when it comes to his struggles and the fear and selfishness that underpinned them. Such was the power of his Olympic obsession that he refused to even think of a cornea transplant—the conventional treatment for the disease would have ended his sledding days. “Olympic athlete was not what I did; it was who I was, and all I had ever thought about being,” he writes in explanation. A focus, it seems, that persists even when you can no longer see.

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary