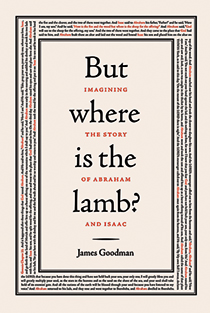

But Where Is The Lamb? Imagining The Story Of Abraham And Isaac

But Where Is The Lamb? Imagining The Story Of Abraham And Isaac

By James Goodman

The story of how God commanded Abraham to take Isaac, “your son, your only son, whom you love,” and sacrifice him as a burnt offering, only to stay the father’s hand at the last minute, takes up just 19 brief verses in the Book of Genesis. But it has generated an enormous and ongoing body of commentary for more than 2,500 years. The tale’s profound silences—about the father’s true thoughts, the son’s reaction (all Isaac gets to say is the title question), mother Sarah’s complete absence, even what really happened (some ancient rabbis thought Abraham did kill Isaac, only to have God resurrect him)—have encouraged, as Goodman notes, even demanded, the wildly variant interpretations.

Over the centuries, Jewish, Christian and Muslim sages—all of whom recognized the sacrifice of Isaac as a foundational moment for their faiths—have provided them; artists, including Caravaggio and Rembrandt, found the scene irresistible; the likes of Kant and Kierkegaard argued over its meaning; sixth-century Syrian hymn writers, like modern feminists, gave voice to Sarah’s anguished reaction; English medieval mystery plays portray Isaac’s bewilderment and, more intriguingly, his distrust of his father even after his life is spared. And many a soldier, bitter at the deaths of the young in the power struggles of their fathers, has felt the story’s shadow. In British Great War poet Wilfred Owen’s take, Abraham ignores God’s command to stop the killing: “The old man would not so, but slew his son / And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”

Goodman—secular Jew, historian, novelist and father—finds something of value in almost all of it in his engrossing book, although he is closest in instinctive sympathy to Bob Dylan. In the song Highway 61 Revisited, Dylan’s Abraham talks back after he hears his orders: “Oh, God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son’ / Abe says, ‘Man, you must be puttin’ me on.’ ” Goodman too thought there would be, should be, an argument: “I thought he’d say, ‘Whoa, hold on, wait a minute. We made a deal, remember? The land, the blessing, the nation, the descendants as numerous as the sands on the shore and the stars in the sky.’ ”

But the fact—the uncomfortable, inescapable fact with which all the Abrahamic faiths have to grapple—remains: Abraham said nothing. Goodman accepts the historians’ premise that the story says something—exactly what is in hot dispute—about both the practice of child sacrifice in the ancient Middle East and the revulsion it evoked even then. But he takes his greatest solace from the way the religious imagination has never accepted Genesis’s unvarnished version.

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary