Cartoonist’s graphic memoir tackles parental old age and death

Review of ‘Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant’ by Roz Chast

Share

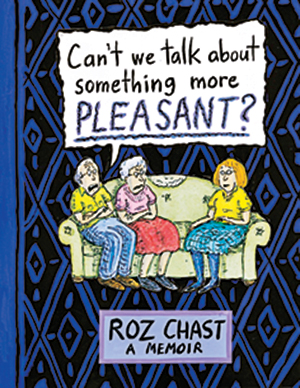

CAN’T WE TALK ABOUT SOMETHING MORE PLEASANT?

By Roz Chast

Few topics are less pleasant to discuss than parental death in old age—the tortuous, indeterminate nature of the decay; how it forces children into a parental role; the way one is never prepared because it’s never discussed. So it’s a surprise and a relief that Roz Chast has taken it on in this raw, unflinchingly candid graphic memoir. The result is an unexpected page-turner that packs the wallop of great art.

Chast, a staff cartoonist for The New Yorker famed for her quavery, wry depictions of everyday angst, brings the same gimlet-eyed observation to her story as the only child of George and Elizabeth Chast, who lived into their nineties and died two years apart. Their lives—and eccentricities—are catalogued with fondness, exasperation and poignancy. Chast’s mother, an assistant principal with whom she had a strained relationship, was bossy and given to rages. Her father, a high school teacher, was her “kindred spirit,” Chast writes, a tentative man perplexed by the workings of a toaster. Together 69 years, the anxious couple shared a dependency that left Chast on the outside (“Aside from WW II, work, illness and going to the bathroom, they did everything together,” Chast writes).

Becoming their caregiver didn’t come naturally, writes Chast, who spares few grisly details: the awfulness of visiting potential “assisted living” centres; self-loathing at her worry about the hideous expense (at one point, monthly care topped $8,000); the indignities of bedsores, dementia and incontinence; and modern medicine’s ability to leave the aged in painful, humiliating, long-lasting “suspended animation”—not living, not dying.

Yet even at its most gruesome, Chast’s memoir, which is punctuated with photographs, her mother’s poetry and line drawings of her mother’s last hours, abounds with kinetic energy and humour. Even after death, her parents are with her, literally, in two urns in her closet after she rejected the suggestion their ashes be comingled. Her mother was so dominant, she wanted her father to have more space in death, she writes—“still close but independent.” Now Chast controls the narrative, sort of — taking a topic her parents refused to confront and defiantly turning it into something people are destined to talk about.