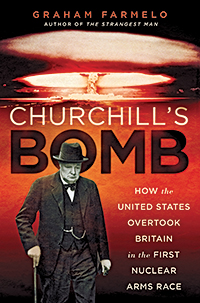

Churchill’s  Bomb: How The United States Overtook Britain In The First Nuclear Arms Race

Bomb: How The United States Overtook Britain In The First Nuclear Arms Race

By Graham Farmelo

Winston Churchill was no Luddite when it came to weapons of war. In the First World War, he showed great enthusiasm for the tank, that new-fangled response to trench warfare. Years earlier, he had urged British officials to reach out to the Wright brothers—to explore the military potential of the new airplane. Early in the Second World War, Churchill’s technological-mindedness revealed itself again; in August, 1941, he became the first national leader to approve the development of a nuclear bomb.

But then, Churchill dropped the ball. He paid only fitful attention to the project. He ignored the great minds of his day, like Niels Bohr—who annoyed the prime minister with his incessant fretting. And then, Churchill made the greatest mistake of all: rejecting president Roosevelt’s offer for Anglo-American nuclear collaboration. (Actually, Churchill ignored Roosevelt’s letter for two months. Suffice it to say, the president got the message.) Within a few years, Britain was left quivering in America’s scientific wake.

Despite the book’s title, Churchill serves more as leitmotif than protagonist. The book is, in fact, a history of the unprecedented wartime collision between science and government: an account of what happened when Whitehall and Washington seized control of the ivory tower’s physics department.

Farmelo’s writing is lyrical—and is chock-full of personality. Readers will delight in (or groan along to) the tale of Churchill’s first meeting with Niels Bohr—which got off to a nasty start, largely because it took place at 3 p.m., “when the prime minister normally liked to begin his daily nap.” Equally enchanting is Farmelo’s retelling of that moment in 1945, when Churchill—unable to keep his secret any longer—shooed away his valet and turned solemnly to his physician, Lord Moran: “We have split the atom.”

Seventy years later, Churchill’s musings on military advancement appear perpetually germane. “In the next 50 years mankind will make greater progress in mastering and applying natural forces,” he wrote, in 1937. “Are we fit for it? Are we worthy of all these exalted responsibilities? Can we bear this tremendous strain?”

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary