Form follows function in Chris Ware’s latest graphic novel

‘Building Stories’ is a Duchamp-like package of 14 separate booklets that vary in shape and size. Try downloading that onto a Kindle

Share

Does anyone reward anal retention like Chris Ware? His comics – a signature meld of fastidious page design, tiny impeccable script and bravura packaging – have brought him an array of accolades. He was the first cartoonist to exhibit at the Whitney Biennial, while his previous opus, Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth, won the Guardian’s prestigious first book prize.

Does anyone reward anal retention like Chris Ware? His comics – a signature meld of fastidious page design, tiny impeccable script and bravura packaging – have brought him an array of accolades. He was the first cartoonist to exhibit at the Whitney Biennial, while his previous opus, Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth, won the Guardian’s prestigious first book prize.

His new work, Building Stories, won’t just increase the applause; it’ll raise the roof. In it, Ware depicts the lives of four inhabitants of a three-storey apartment building in Chicago: the spinster landlady, an unhappy couple, and the main protagonist, a lonely young woman who eventually moves out to the Oak Park suburb to start a family with her architect husband. The building itself, in the voice of a sweetly brassy dame, even has a tale to tell, as does a wayward bee looking to pollinate nearby flowers.

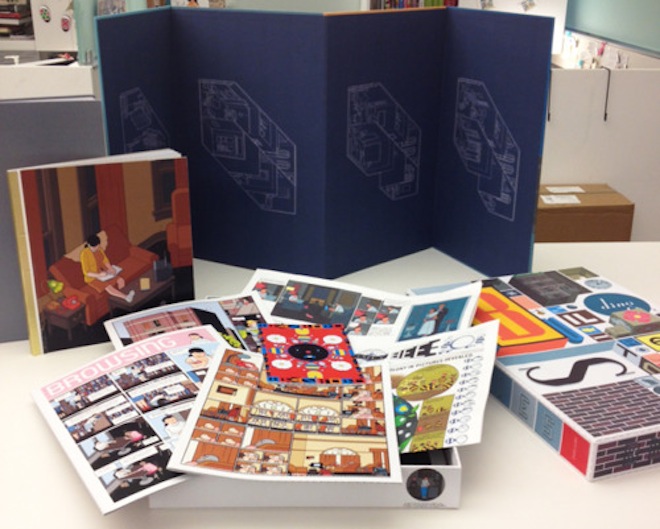

Fittingly for its title, Building Stories adheres to that old architectural saw: form follows function. The “book” is actually a collection of 14 separate booklets of varying shapes and sizes, including traditional comic book-style pamphlets, huge broadsheets that recall the old Sunday funny pages, two clothbound volumes (one with a replica design of the classic kids series Little Golden Book on the inside covers) and a fold-out game board. Building Stories is, in fact, collected in a board game-shaped box. Ware, an afficianado of 20th century print ephemera, cites Marcel Duchamp’s Musuem in a Box as an influence, but the work is also reminiscent of The Unfortunates, avant-gardist B.S. Johnson’s novel that consisted of 27 unbound, box-encased chapters. Regardless of provenance, Ware is offering a riposte to digital publishing: Building Stories is not Kindle-able.

The format also allows Ware to indulge his taste for non-linear narrative. Read the booklets in any order and the story remains the same; offhand references in one strip – to the young woman’s ex-boyfriend or to the loss of her lower left leg in a boating accident – are elaborated upon in another. Comics are particularly well-suited to this sort of temporal play. The medium’s main component, the panel, is a deft manipulator of time. It can freeze the action, move it incrementally forward, or jump back a generation and Ware takes full advantage of his resources. The elderly landlady, for instance, requires six panels to drink a glass of milk, but can be transported back to toddlerhood in two.

All of Ware’s people, though simply rendered in the manner of Frank King’s Gasoline Alley, are put through elaborate paces on the page. They traipse through memory, tiptoe around word balloons and take circuitous routes until they come face-to-face with each other, or, more importantly, themselves. For all of Ware’s visual efficacy, his writing is informed by a singularly sadsack mentality. His characters are desperately anxious and larger external events, such as a lost cat or dying father, are often dwarfed by incessant niggling doubt. They find little solace in their half-hearted attempts to communicate with those closest to them. One of the booklets begins with the word Disconnect in large letters. When words fail, Ware falls back on pictures. He artfully arranges his panels and his pages, uses them as building blocks to contruct tangentally connected lives. In other words: he masters the form.