Giving Otis Redding the ‘Respect’ he deserves

Book review: Full of bold claims (and dodgy allegations), a new biography makes the case for Otis Redding

UNSPECIFIED – CIRCA 1970: Photo of Otis Redding (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Share

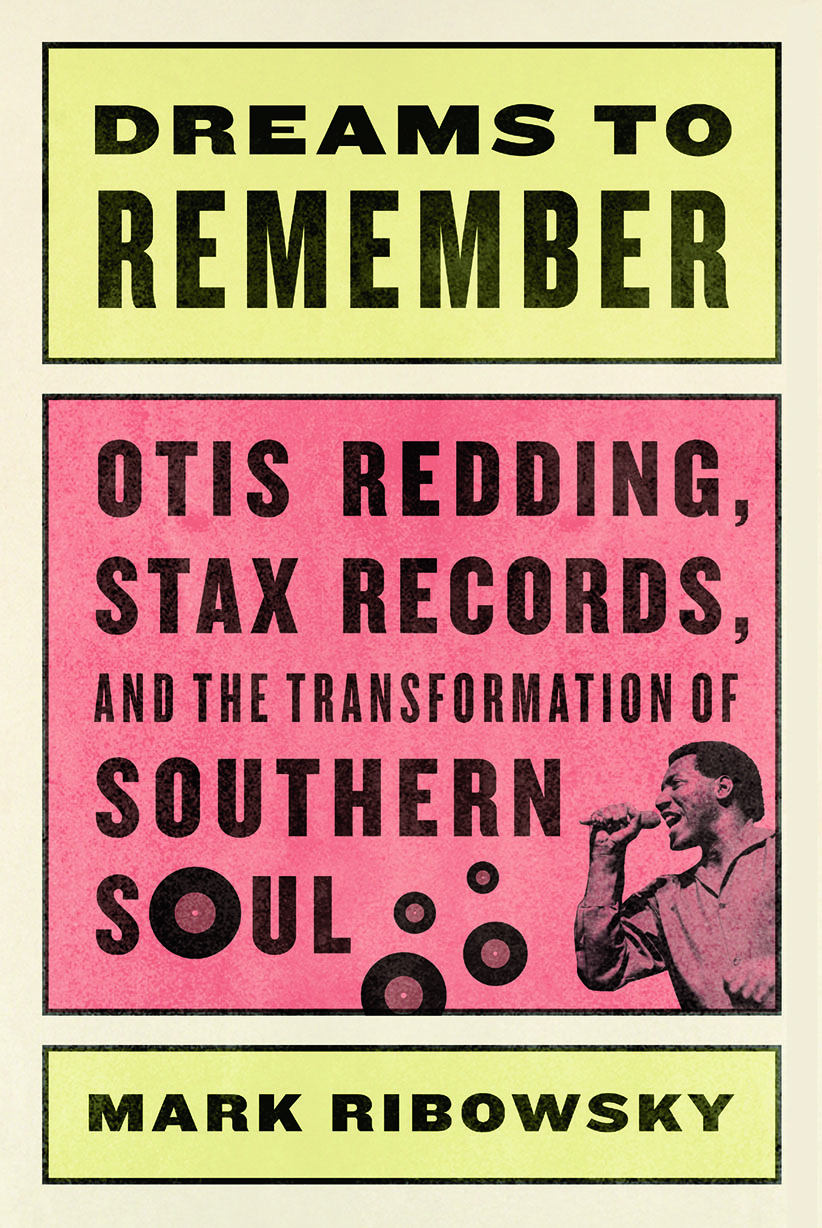

Dreams to Remember: Otis Redding, Stax Records, and the Transformation of Southern Soul

Mark Ribowsky

In the introductory chapter, Ribowsky boldly claims that two songs “reveal everything there is to know about the meaning” of the 1960s: Respect and (Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay. The first was written by Otis Redding and made famous by Aretha Franklin, the second is Redding’s one and only pop hit, released just after his 1967 death in a plane crash. (Historically, it’s No. 6 on the list of most-played songs on the radio, as of 2011.) Both are stirring, inspiring, durable recordings—no argument there. And “the Big O” was the most dynamic and charismatic singer on the second-most-popular R&B/soul label of the day (after Motown), Stax. But Ribowsky risks writing a hyperbolic hagiography of a man who was a distant third in influence behind James Brown, who revolutionized pop music itself, and gospel crossover pioneer Sam Cooke. That’s his prerogative, of course, and this biography works because Ribowsky—who’s also written books about the Supremes, the Temptations and, um, Howard Cosell—is able to articulate the excitement in Redding’s music that made fans out of anyone who heard it.

Ribowsky claims to be telling the story of Stax Records, as well, a topic best left to Torontonian Rob Bowman, author of Soulsville, U.S.A., the definitive document on the topic, or Peter Guralnick, who, in Sweet Soul Music, seamlessly weaves together the various threads of Southern soul. But Stax is important here, because it was Redding whose success made the label into the force it was, who made a bid to shift the focus from singles to albums, who became a millionaire in doing so. When Redding died—just before, some say, he was going to abandon Stax for parent company Atlantic—Ribowsky claims Stax’s fortunes went down with him. Which is partially true: The label’s founders were heartbroken, and were soon squeezed out of the business by Atlantic. But it’s also ridiculous, because Stax soldiered on: Isaac Hayes soon became a groundbreaking superstar, the Staples Singers crossed over into pop, and the triumphant Wattstax concert and film were five years in the future. Ribowsky works best when he sticks with Redding.

There has been one other major Redding bio: Scott Freeman’s 2001 Otis!, which Ribowsky chastises for including salacious rumours—over which Redding’s widow and manager sued Freeman for $15 million and settled out of court. Yet Ribowsky repeats those very same rumours, and includes some new dodgy allegations, as well, even if he brings them up only to shut them down. But, 50 years after Redding recorded Respect, when Motown is erroneously remembered as the only wellspring of R&B and soul in the ’60s, the stories of Stax and Redding deserve to be told again and again.