How Canada planned to invade the U.S. (and vice versa)

A new book offers an unintentional guide for Canada to conquer America. If, for some reason, we ever wanted to try to do that.

War Plan Red by Kevin Lippert. (Princeton Architectural Press)

Share

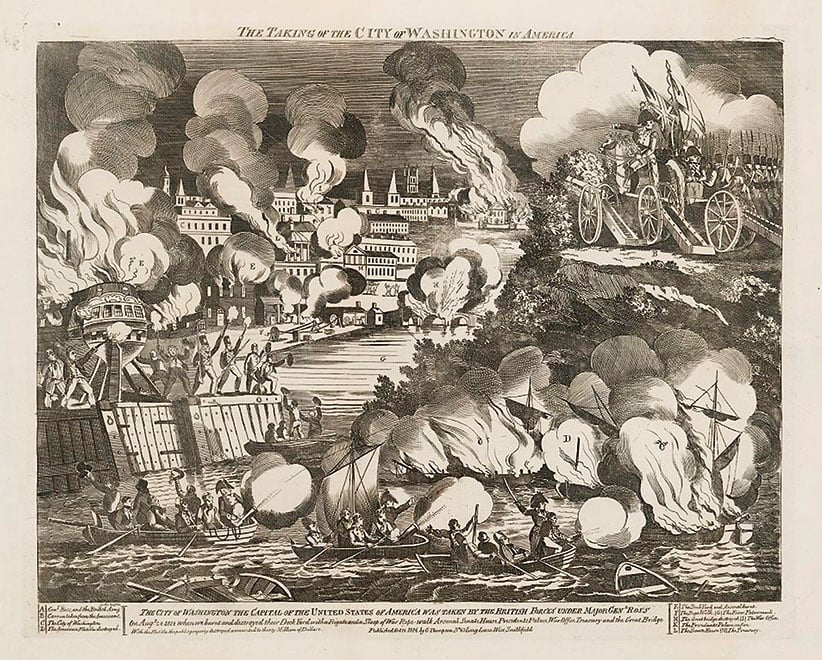

Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. So if any misguided Canadian prime minister ever gets it in his or her head to wage war on the United States, it might not hurt to brush up on past attempts to conquer our southern neighbour. Some of our previous incursions were roaring successes (Canada, or if you want to get picky, the British, burned down the White House) and we can always learn from our embarrassing failures (like that time we almost went to war over a pig. More on that later.)

Fortunately, Kevin Lippert has a new book out, War Plan Red, detailing the more-than-200-year history of border skirmishes between the United States and Canada. It’s $5 cheaper in the United States (another reason to invade) and contains all the historical context one might need to reclaim Maine for Canada (you won’t read about it in American history books, but Canada conquered Maine in 1814). The most intriguing parts of the book are the two maps showing Canada’s plan to invade the United States (circa 1921) and America’s plan to invade Canada (circa 1930).

How Canada planned to take America

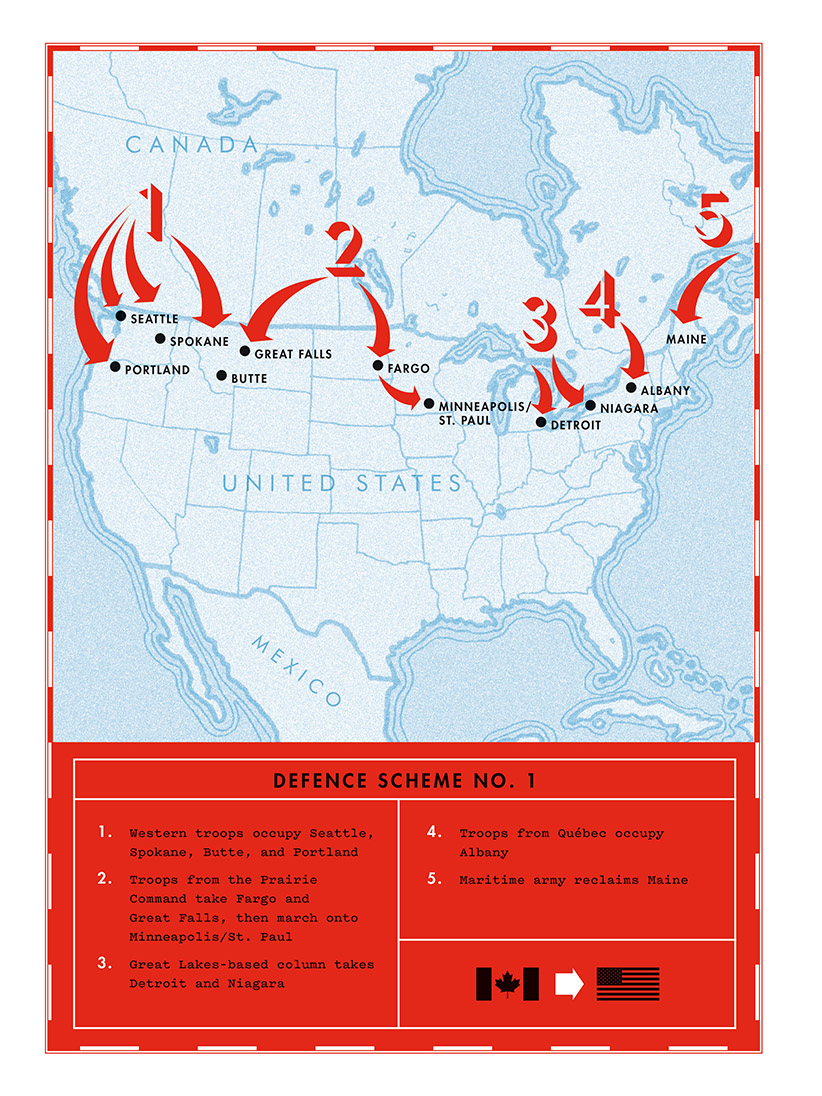

In April 1921, Lt.-Col. James “Buster” Sutherland Brown, Canada’s director of military operations and intelligence, drafted the Canadian plan to invade the United States, known as Defence Scheme No. 1. While Brown is often described as a loose cannon, he was actually following orders from the chief of the general staff, who was concerned about an American invasion. After the First World War, America began to supplant Britain as the pre-eminent global power (Britain owed America $22 billion after the war) and so the concern that Canada might once again become a battleground for conflict between the two more powerful countries made some sense.

Brown went deep behind enemy lines (about as far as Vermont) while doing research for Defence Scheme No. 1. In his notebook, Brown described a large number of Vermont men as “fat and lazy but pleasant and congenial” and rural Vermont women as “a heavy and very comely lot.” Despite these sophomoric observations, Brown was actually an excellent commander who had distinguished himself during the First World War with his skills in planning and logistics. Certainly he was a better strategist than American Brig.-Gen. William Selby Harney, who almost started a war over a pig—when an American shot a British man’s pig on San Juan Island (in modern-day Washington state), Harney brought in 500 troops from Oregon, culminating in a standoff against 2,000 British soldiers that was ultimately defused with only one fatality: the pig.

Brown’s plan to conquer America called for a lot more fatalities than just one. He intended to divide the Canadian army into five flying columns, each of which would capture key American cities, destroy crucial infrastructure, then run away as soon as a large American force counterattacked. The hope was that by destroying bridges and ripping up train tracks while retreating, the United States would be delayed enough that Britain and the rest of the empire could come and finish the job. Brown’s plan got mixed reviews among Canadian military leadership (his successor hated it so much he ordered all copies burned) but it nonetheless remains the last public Canadian plan to invade the United States.

One fun fact: notice that point 5 in the above map reads, “Maritime army reclaims Maine.” The word “reclaims” is appropriate because during the War of 1812 Canada conquered Maine, and used the taxes it collected to found Dalhousie University. The Canadian plan may seem silly but it’s worth noting that the American plan follows roughly the same path—except that they considered using chemical weapons.

How America planned to take Canada

By May 1930, when the Americans came up with their scheme to invade Canada, called War Plan Red, senior American officials were seriously considering the possibility of a war with Britain. The Americans shared the same concern the Canadian drafters of Defence Scheme No. 1 had back in 1921: namely that growing economic competition between the United States and Britain could boil over into a military conflict with Canada as the battleground.

In February 1935 the United States spent $57 million to update their plan to invade Canada. They built three military airfields disguised as civilian airports near the border and staged the largest war game in U.S. history up to then, with 36,500 soldiers drilling, marching, and dreaming of maple syrup. War Plan Red was remarkably similar to Canada’s Defence Scheme No. 1. Troops from Detroit would seize Toronto while Albany and Vermont troops would march on Quebec City and Montreal.

The plan relied on ships out of Boston blockading Halifax and stopping British troops from reinforcing the Canadians. According to the plan, the British would be able to muster 2.5 million soldiers from across the empire so stopping them from landing in Halifax was critical. America’s plan had a darker side too. Famous aviator and suspected Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh flew reconnaissance missions over Canadian airspace and recommended that chemical weapons be used.

Today, these two war plans are historical footnotes, amusing anecdotes about a conflict that never happened and almost certainly never will. But they’re enlightening nonetheless. Lippert’s book contains extracts from both the American and Canadian invasion plans that eerily echo the rhetoric around more recent foreign interventions in the Middle East—both sides claimed they’d be welcomed by the local populace and hinted that they’d win with minimum loss of life and maximum accumulation of glory. No matter which continent or century they’re in, it seems that would-be conquerers could stand to learn something from the past.