Inside Atlanta when Martin Luther King died

Plus, Gordon Brown’s take on the global financial crisis, a promising new novelist, the return of Russia, an ordinary man’s miracle and a life told through yoga poses

Share

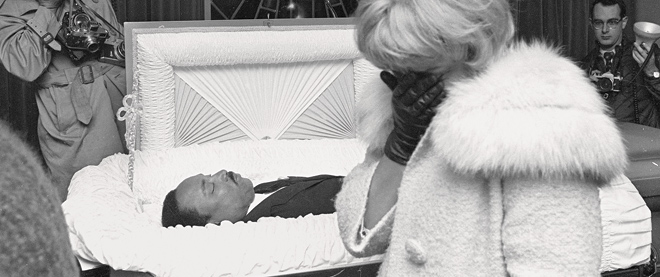

Burial for a King

Burial for a King

Rebecca Burns

Less than an hour after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., shot while standing on the balcony of his Memphis, Tenn., motel room, was officially confirmed on the evening of April 4, 1968, the first window was smashed in Washington. Five days of rioting in the U.S. capital eventually killed 12 people and destroyed 1,200 buildings, some only two blocks from the White House. In all, violent disturbances broke out in more than 100 American cities after King’s assassination. But not in the city where rioting might have been most expected: Atlanta, King’s hometown and the site of his emotionally laden funeral. Burns’s book explores why that peace, sometimes stretched to the breaking point, held in her city. Despite palpable tension, the April 9 ceremony—highlighted by the burial procession of King’s mule-drawn hearse and 150,000 mourners—went off without serious incident.

Burns is a former editor-in-chief of Atlanta magazine, and it shows: much of her intricate description of the politicking among Atlanta power brokers, white and black, will be of interest mostly to Atlantans of long memory. Yet that insider knowledge also informs Burns’s persuasive analysis of what made her southern city different from, say, Birmingham, Ala., and her account of how Atlanta’s oh-so-slow desegregation crumbled within days into almost complete institutional racial integration. (White churches that had long struggled over the question integrated overnight under the necessity of accommodating black co-religionists, as did the city’s hotels, still 80 per cent segregated on the day King died.)

And she has a wealth of anecdotes to propel her story along. On April 5, Robert Kennedy, who would be shot to death himself only two months later, on his own initiative sent a technician to install more phone lines in the King home, and promised to help navigate the “protocols” involved in hosting foreign VIPs. “My family,” Kennedy told the grief-stunned King entourage, who had not yet thought through the logistical nightmare to come, “has experience in dealing with this kind of thing.”

Brian Bethune

Beyone the crash: Overcoming the first crisis of globalization

Beyone the crash: Overcoming the first crisis of globalization

Gordon Brown

The global financial crisis was Gordon Brown’s best shot at saving his faltering premiership of the United Kingdom. He had excelled as chancellor of the exchequer (equivalent to our finance minister) for 10 years while his friend and then rival, Tony Blair, was prime minister. And when Britain’s economy began to slide, Brown’s experience and dour gravitas seemed for a moment to outshine his more obvious flaws, such as a lack of charisma and inability to connect with people. Brown understood the magnitude of the problem and put together a rescue package for British banks, and then pushed world leaders toward similar bailouts.

It wasn’t enough, of course—at least not for Brown’s political career. His Labour Party lost the May election. Brown, though still an MP, has used the time since to write this book about the crisis, its roots, his role in tackling it, and what he believes must now be done to ensure something similar doesn’t happen again. The former prime minister is not a frivolous man, and the book is appropriately serious. It’s also boring. The prose meanders; the reader’s eyes start to wander. Accidentally skip a page and you might not notice.

Still, there is nobility in Brown’s efforts here, as there was in much that he attempted and failed to do as prime minister. Brown could have sold many more copies of a book that recalled his political career and told the story of a decade’s infighting in the Labour Party. Even the odd shot at Tony Blair probably would have been good for a few thousand sales. But there is no political dirt in this volume, and little that’s revealing about Brown himself. We learn what sort of pens he likes to use but not much else. Still, Brown’s arguments about the need for greater international co-operation in financial matters are convincing, and his commitment to social justice appears genuine and firm. Brown wasn’t a successful prime minister, and he’s a not a particularly good writer. This book’s a slog. But it’s hard not to respect the author when you finish it.

Michael Petrou

The metropolis case

The metropolis case

Matthew Gallaway

A new year is a great time to get acquainted with brand-new novelists, and based on his musically attuned, wonderfully paced debut, Matthew Gallaway’s name will be on a lot of readers’ lips and minds as 2011 progresses.

Gallaway gave himself no easy task: conjure up several interlocking time frames spanning more than 150 years, two continents and various calamities (9/11 weighs heavily in one strand of the narrative) to convince us opera still matters—and especially the high melodrama that is Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, the German composer’s 1865 epic tragedy of two star-crossed lovers.

The opera means something different to each of Gallaway’s quartet of narrators: for Lucien, it’s the role that will cement his status as Vienna’s leading heldentenor, curry favour with Wagner himself and make sense of his own burgeoning homosexuality. For Anna, a rising 1960s opera star, it’s the basis of a secret manuscript entrusted to her and an even more secret, fleeting love affair. For Maria, a big-voiced misfit teen in 1970s Michigan, it’s a ticket out and a conduit to potential greatness. And for Martin, it is a way to escape the practice of law and a way of asserting some larger artistic hopes and dreams.

The characters interact in both expected and surprising ways, so that seemingly innocuous actions beget both disastrous and wondrous consequences common to Wagnerian dramas. Gallaway also steeps the reader in long-ago Vienna while seamlessly moving to the New York City of various generations, the grime of three decades dissolving into the gentrified post-9/11 world, where there’s still room for tragedy and confusion.

As Lucien sagely notes, “There was no point making distinctions between art and love; as with air and water, he needed both.” The blurred distinction is at the magical heart of The Metropolis Case.

Sarah Weinman

The Return: Russia’s journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev

The Return: Russia’s journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev

Daniel Treisman

There are two points that Treisman, a political scientist at UCLA and a former consultant on tax reform to the Russian government, wants to make clear in his entertaining narrative account of Russia’s last quarter century. First, like it or not, Russia is back engaged with the world again, once more one of the most important nations on the globe. And second, despite Russia’s less than stellar image abroad—as a mafia-ridden, quasi-fascist disaster—that return is no bad thing. Nor is Russia’s sinister reputation deserved, Treisman argues persuasively. Its situation is actually typical of countries at similar levels of economic development. Russia is unique, he writes, but in the same way “Argentina and Malaysia are unique—no more, no less.”

Its economy, for instance, dominated by wildly fluctuating natural resource prices, looks like any second-tier country such as Thailand or Brazil. As for corruption, Treisman plots a graph—based on the fact corruption lessens as national income rises—comparing reported bribes with GDP per capita. Russians are found on it where their incomes would predict: they report paying bribes more often than Hungarians but less often than Mexicans. “Unique” Russia actually looks a lot like Turkey, where democracy is umpired by the military, where a newspaper that wrote about government corruption was fined $525 million for “tax irregularities,” where the state’s inner workings seemed revealed by the 1996 crash of a speeding Mercedes: inside were found “a police chief, a prominent parliamentarian, an internationally wanted hit man and a former beauty queen.”

Of course, “not so bad” doesn’t exactly mean “good.” Russia isn’t Switzerland, and it does bristle with nuclear weapons. For all his sympathy, Treisman freely acknowledges the nation’s problems, particularly the tensions that threaten its stability whenever oil prices dip. But his key point remains: Russia is “too large to ignore and too large to co-opt.” If the West is ever going to engage with it meaningfully, we’d best start with an accurate picture.

Brian Bethune

The Third miracle: An ordinary man, A medical mystery, and a trail of faith

The Third miracle: An ordinary man, A medical mystery, and a trail of faith

Bill Briggs

If a miracle can be described, colloquially, as just what you need (in defiance of the laws of nature), just when you need it (but had no right to expect it), then the occurrence at the core of Briggs’s book partook of the miraculous in more ways than one. Ten years ago, Phil McCord, a not particularly devout Baptist handyman at a Roman Catholic convent nestled in rural Indiana, was a desperate man. In the wake of cataract surgery gone wrong, McCord’s right eye was a pulsing mass of infection, and his only chance at recovery was a risky procedure. On impulse he stepped into the convent chapel and made a spontaneous prayer for the help of God and—crucially—the convent’s formidable, if long-dead, founder, Mother Théodore Guérin. The next day his eye was suddenly, almost totally, better. McCord and his doctors had no explanation, but for the nuns of Saint-Mary-in-the-Woods, there was no doubt. For them too McCord’s healing was just what they wanted, just when they needed it: the long-desired second miracle in their case for canonizing Guérin as the eighth American saint had finally occurred, more than 90 years after the first one. Now that an argument could be made for two miracles, the threshold for canonization, Guerin’s century-old case could go forward.

The main narrative thread in this intricate story follows the bewildered Baptist’s immersion in the ancient rituals of Catholic saint-making, from the original trial in the headquarters of the archdiocese of Indianapolis (where priests grilled doctors about supernatural healing and probed for weak spots in the sisters’ claim) to the final decision in Rome. But the true theme of Briggs’s marvellously evocative account of a singular collision between the physical and metaphysical realms lies in the third miracle of his title: McCord’s dogged quest to come to terms with what had happened and, above all, why it had happened to him.

Brian Bethune

Poser: My life in twenty-three yoga poses

Poser: My life in twenty-three yoga poses

Claire Dederer

About 10 years ago, Claire Dederer threw out her back while breastfeeding her baby. “Nursing, at least where we lived in Seattle, was a strange combination of enthusiast’s hobby and moral mandate,” she recalls, skewering the self-flagellating world of new moms. In her quest to be perfect, Dederer enrolled in a yoga class to help strengthen her back and maybe even calm her nervous tremor. “When we finished up in savasana, I didn’t feel like I’d worked out. I felt more like I’d churched,” she says, using the kind of language often missing in books about yoga. Dederer refrains from peppering the text with insider yoga jargon, and instead assumes the role of hapless initiate. The result is unfailingly hilarious: “The women sat cross-legged, with straight backs. They all gazed straight ahead into the middle distance, as if they were about to break out into a collective fit of landscape painting.”

But Poser is more than a cheeky yoga chronicle. It’s a full-on memoir, covering Dederer’s unorthodox childhood, her extended youth, her career as a freelance book reviewer, her faltering marriage and her crushing fear of failing as a parent. The book’s structure is a bit gimmicky, matching sections of her life to specific yoga poses, but this can be forgiven because of her strong voice and wisecracking style. She searches for the right yoga teacher as she searches for the right way to live. To Dederer, taking a walk with a childless girlfriend is like “taking a peacock out on a leash,” and she likens date night with her husband to a “strange Ponzi scheme of obligation.”

Only one speed bump: when Dederer stops to deliver a history lesson about feminism. It’s redundant, since stories of her parents’ unique un-marriage make the same points in a more engaging manner. Same with the backgrounders on yoga. Is there too much yoga in Poser? No. There’s too much pouring of coffee. Dederer didn’t drink a cup she failed to mention. Then again, she was living in Seattle, wearing clogs.

Joanne Latimer