Starring Oslo as Gotham City

Famed for his part in Scandinavia’s noir boom, Jo Nesbø has a few other careers, too

Brian Howell

Share

Before arriving in Vancouver for October’s International Writers Fest, mega-selling Norwegian noir novelist Jo Nesbø toured some of the danker corners of Chicago with a local crime reporter. “I did some calculating,” he says. “It’s probably 20 times as many murders per capita in Chicago versus Norway.” You wouldn’t know that from the dark, violent Norway that is the setting of many of his crime novels, including Police, just out in English translation and Nesbø’s 10th outing with Harry Hole, the Oslo police detective known to abuse his liver and his superior officers with equal enthusiasm. For all his moral quandaries, doubts and conflicts, Hole is invariably the smartest person in the room—and usually the room holds a corpse.

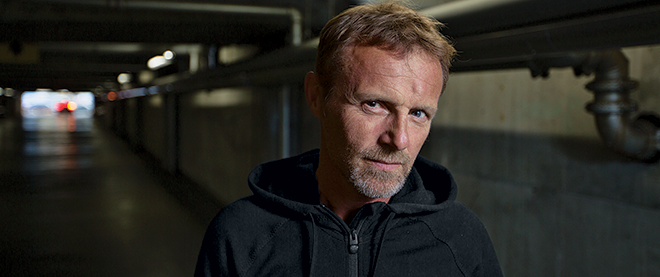

It’s one of life’s mysteries that some of the best crime novels of the past two decades have come from Scandinavia, out of countries which boast some of the world’s lowest murder rates. Among many others are Henning Mankell and the late Stieg Larsson, both from Sweden. Then there’s Nesbø, a 53-year-old Renaissance man who has had stints as a semi-pro soccer player, soldier and stockbroker, and is also currently the lead singer for Di Derre, a Norwegian pop band. Facing burnout some 15 years ago, he decamped to Australia and wrote The Bat, his first Hole novel, published in 1997. Success, he says, was “a slow burn,” with each new work fuelling the fire. With Police, Nesbø’s book sales now exceed 20 million in 40 countries. In 2011, an action movie based on his novel Headhunters became the highest-grossing Norwegian film of all time. Two more movies are also in development, one based on The Snowman, a Harry Hole novel; the other on Blood on Snow, a novel written by Nesbø as his “alter-ego” Tom Johansen. There are rumours Leonardo DiCaprio has signed on to star. “It’s Hollywood,” Nesbø says. I don’t believe anything until they call me and say they’re shooting now.”

What he can control are his plots, with their labyrinthian twists and blind alleys. Police, for instance, begins with a nameless man in a coma in a guarded hospital room, a series of elaborately staged police murders and the unsettling possibility that Hole—apparently killed off in the previous book, Phantom—is not among the living.

Nesbø has no compunction about bloodying Norway’s reputation. While hardly a crime capital, he says Oslo has been “heroin-ridden” since the 1970s. “The Oslo that I use is 90 per cent the true Oslo; 10 per cent, it’s a twisted, darker, Gotham City version of Oslo,” he says. “Then again, I don’t have to twist it too much.”

Sad but true. In July, 2011, the nation was rocked to its core when Anders Breivik, a madman with a muddled far-right, anti-Islamic, anti-feminist agenda, bombed government buildings in Oslo, killing eight people, before storming Utoya island in a mass shooting that left 69 dead, mostly teens at a Labour Party youth league camp.

The trauma of Utoya is a shared national memory. “It will stay with us for the rest of our lives,” he says. Certainly it did nothing to lighten the dark ruminations of his books. “I’m sure it already has ended up on paper. I can’t see how. But I’m sure it’s there.” While the massacre has been called Norway’s 9/11, he says there are profound differences that informed each nation’s response: America’s anger and paranoia; Norway’s sad stoicism. An ideological army was deployed against the U.S., while Breivik was one individual, “more like a natural disaster, an earthquake or avalanche, that could happen anywhere, at any time.” When the Labour Party gathered in the aftermath, they held an open meeting without security. “They made a point of that: ‘Let’s not be afraid,’ ” he says. “The United States, they had a reason to be afraid. It was rational to take security measures.”

He’s grateful that Norway hasn’t locked itself down in similar fashion, “because that would be a society with so much security and suspicion and fear that it would be hard to live in.” He winces at a paradoxical thought: that freedom and openness are worth preserving, even if they sometimes come at a cost. “I hope we will have a society where a massacre like this could happen again.” But some things are best left to fiction.