Life in Churchill’s school for spies

A review of The Secret Ministry of Ag. and Fish

Mandatory Credit: Photo by REX USA (256236l)

Share

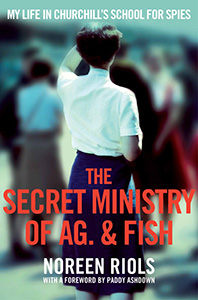

THE SECRET MINISTRY OF AG. & FISH: MY LIFE IN CHURCHILL’S SCHOOL FOR SPIES

By Noreen Riols

Her first day on the job, 18-year-old Noreen Riols was told to ask no questions—and to tell no one where she was. Riols kept her word. For the duration of the Second World War, her own mother thought she worked at the British Ministry of Ag. and Fish.

Far from it. In 1943, Riols was recruited into the Special Operations Executive (SOE), known colloquially as Churchill’s “secret army.” (He had furtively founded the SOE without parliamentary approval in 1940.) “Churchill understood from the very beginning that this was going to be different from any other war,” writes Riols. “The gentlemanly warfare Britain had always fought was not possible . . . only the ungentlemanly schemes would succeed.” Riols’s memoir recounts the best and worst of those schemes.

In 1943, while studying at the French Lycée in London, Riols was served with call-up papers and given the option of working in a munitions factory or joining the Women’s Royal Naval Service. She opted for the latter, but, within days, she was seconded to SOE HQ and assigned to “F Section,” which supported the Resistance in occupied France. Riols spent much of the ensuing years helping train would-be British spies. One duty was to act as a decoy in training drills. In one exercise, recruits had to meet Riols at a telephone booth in Bournemouth and whisper her a secret message—without moving their lips.

This memoir oozes wartime intrigue with its tales of double agents, parachute drops by moonlight and secret codes hidden in crossword puzzles. Yet, throughout, Riols remains fiercely unsentimental—recounting excruciating stories in excruciating detail: as, for instance, with the British agents who were cremated alive at a concentration camp in Alsace. The book is equal parts memoir and institutional history: of a secret unit that, after the war, largely faded from public memory.

Why this forgetting? Riols writes scathingly of Britain’s long-serving military intelligence body, MI6, which she says worked to sideline the SOE and its “guerrilla tactics.” Similarly, she doesn’t mince words about Gen. Charles de Gaulle, who thought his Free French forces could bring about the liberation of France without SOE assistance, thank you very much. After the war, in 1945, much of the SOE archive was destroyed in a “mysterious” fire.

This reviewer wonders if readers will draw unintended historical parallels: to a modern-day U.S., where the secret intelligence activities of rogue spy agencies have been, similarly, brought to light.