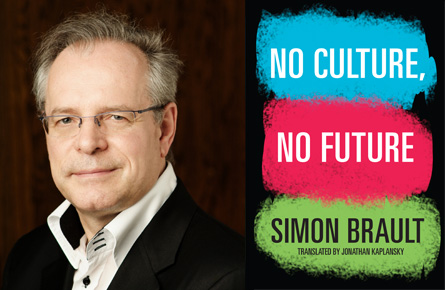

Maclean’s Interview: Simon Brault

CEO of the National Theatre School on what culture means to Quebec, Canada, and the Conservatives

Share

Simon Brault is both a member of Canada’s cultural establishment and an iconoclast dedicated to its reimagining. CEO of the National Theatre School and Vice-Chair of the Canada Council for the Arts, Brault is also chairman of Culture Montreal, a grassroots organization that over the last decade brought together governments, business, and Montreal’s arts community to design and pay for a cultural renaissance in the city. His new book, No Culture, No Future, originally published in Quebec as Le Facteur C, is a defence of culture in three parts: a survey of policies historical and ideal, a philosophical rumination on the centrality of culture to human life, and an account of Brault’s ongoing efforts to turn Montreal into an international cultural capital.

Q: What reaction has the original French version of your book received since its publication last Fall?

A: I was surprised to see that the book was primarily covered by journalists interested in public affairs, politics and urban activities, and only later by people reviewing books and culture, which actually confirms the book’s arguments that culture has implications for all aspects of society.

Everybody said if you write an essay on culture nobody would read it, but the book was a commercial success. And in Quebec I think it’s reframing the discussion about the importance of arts and culture at different levels of society. It’s a bit surprising since I’ve been making these arguments consistently for 15 years. I didn’t expect that in this age a book would have such an impact.

Q: I was living in Quebec City during the last federal election and watched the province-wide meltdown of the Conservative campaign after Myriam Taschereau, a Tory candidate, said that “artists are spoiled.” Why is arts funding so important to the people of Quebec?

A: It’s clear that in Quebec there was always and remains a direct link between culture and a sense of identity. There has always been a clear connection between having cultural policies and protecting the French language. For Quebecers, culture is a reflection of who they are, of their right to exist, to be different, to speak French and all of that. What was really important about the last federal election is that culture became an issue in a federal campaign for the first time ever in Canada. Even if it was for all the wrong reasons, it provoked a sense of awareness among politicians about the importance culture has right now, both inside and outside of Quebec.

But for me, as a member of the artistic community, I also realized that our community was not really able to foster a discussion beyond protesting. A lot of the arguments that were made against the arts cuts were quite self-serving or defensive, without regard for consequences for Quebeckers and Canadians outside of the community. That’s one reason I decided to write this book – to connect the various parts of the community and to work out some arguments that might start a discussion rather than just complaining or protesting or being cynical.

Q: Do you think the criticisms of the Conservatives’ culture policies were deserved?

A: What hurt the Conservatives most during the last federal campaign was not so much that they decided to cut culture spending, but more the discourse. The government said they were making the cuts because artists were giving Canada a bad image, that they had bad taste. Nobody can say that they slashed culture – like almost every government in the world, Harper is spending more on culture than any government in the country’s history – but it’s clear that after the last election, they had to fix things and establish a sense of trust between them and the artistic community. And [Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages] James Moore is obviously on a mission to build bridges, and I think in some instances, such as with the Canada Council – protecting its budget and even increasing it – he’s succeeded. It’s clearly not natural for them, they’ve clearly never considered it important, but after the election, they’re aware that it could be damaging if it’s not well managed. And I would call that progress.

Q: How does a country with a population roughly equivalent to Tokyo’s, spread across an enormous land mass, create a cultural community as vibrant as those in more densely populated areas?

A: Density is certainly a factor of building a vital cultural sector, and that’s why most of the major cities in Canada do have a vibrant arts scene. For years we had a vision of culture as top down, from government down to the people, but now we see that cities are really the hub of cultural creativity. And I think in Canada we have cities that can easily compete with the rest of the world, not only because of their size but because of their diversity.

It’s very interesting to see globally how cities are becoming cultural engines, because they concentrate a lot of the civilization’s challenges – the challenges of trying to live together.

Q: Given that cities are becoming increasingly important to the cultural vitality of countries, do Canada’s cities have sufficient independence and resources to meet this challenge?

A: It’s difficult in Canada. If you look at Canada compared to many European countries, you can see that local governments and municipalities don’t have large capacities in terms of making decisions and shaping the way they are organized and operated. Federal and provincial governments still have a lot to say, especially with regard to culture.

Even twenty years ago, you wouldn’t have imagined that people would say that a way to transform and rethink the city is culture. But it’s clear now that if we want to see a real cultural boom in Canada more power has to be given to cities. And I think it will happen not only because of culture but because of the economy and environment, too. The movement is slower in Canada than in the rest of the world, but it will happen. It’s the demographic and economic reality.

Q: You write at length about the economic benefits of cultural investment, but you warn policymakers not to limit their arguments in favour of culture spending to the economic. What do you see as the intrinsic value of culture?

A: Arts and culture bring to any society the capacity for self-expression, for citizens to say out loud their malaise, or their joy, or their difficulties. Self-expression is absolutely important because if it’s not expressed in artistic creation and in culture it will inevitably be expressed in violence and confrontation and wars and exclusionary beliefs. I think culture is the way to make sure that human beings can still share values. It seems abstract, but at the same time, it’s vital in order to maintain our capacity to live together in a world where people are more and more isolated and where situations are more and more complex.

Q: Despite the book’s alarming title, No Culture, No Future strikes me as more hopeful than despairing. You acknowledge in the book that we live in a time beset by crisis and complex problems without obvious solutions, and yet rather than disengage, you build a grassroots movement that successfully lobbies for hundreds of millions of dollars in arts and culture funding. How do you keep the faith?

A: Because I think that culture is one of the driving forces of society. Culture has the power to transform individuals and society, and I see in that fact a way to protect and advance civilization. With culture, you can have a grasp on the future of the world. And I think it’s important to remember that transformative power at a time when we feel so powerless.