Correcting a simplistic view of the Soviets

The Maisky Diaries provides a rare glimpse into Stalin’s Soviet Union

Share

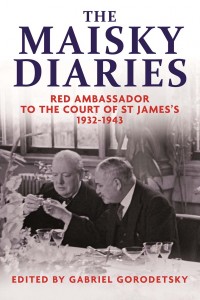

Edited by Gabriel Gorodetscky

Ivan Maisky was an enigmatic charmer who was clever enough to succeed in London as Soviet ambassador from 1932 until 1943, when the Soviets urgently needed to establish strong relations in Europe, especially with Britain, and counter the growing German threat. This was the time of Stalin’s terror, which Maisky survived mostly, it seems, because he was so useful. The same went for trivialities like the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression agreement—the Winter War with Finland, and the German invasion.

It was not a period when many senior Soviet officials dared to keep personal diaries, let alone ones as vivid as Maisky’s, which are now finally published in English. Discovered in 1993 and edited by the historian Gabriel Gorodetsky, the diaries are only the beginning of the surfacing of an enormous new archive with the potential to change our understanding of the decade that led to the Second World War and laid the groundwork for the Cold War. This 584-page book is the condensed version, with limited annotations, of what is promised to be a three-volume set with abundant cross-references. The Soviet historian on your Christmas list will have to wait.

Though Maisky wrote five memoirs (as well as books of fiction), they were published in the long shadow of his political rehabilitation after finally being arrested in 1953. (He was charged with espionage and treason.) So the diaries represent some of the only uncensored records of the affable ambassador’s encounters with Lloyd George, Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain, Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden, a handful of kings, Bernard Shaw, and H.G. Wells, among many others.

That Maisky had a diplomatic career at all is astonishing since he had joined the only armed socialist opposition to the Bolsheviks after the revolution. This would haunt him, but somehow it did not get him shot or prevent him from bouncing between several important government jobs before his first diplomatic posting to London, followed by a two-year apprenticeship in Tokyo, and another in Helsinki, where he orchestrated the signing of a Non-Aggression Pact with Finland and made himself eligible for a return to London.

This book covers political strategy and daily life in a sweep that is a welcome corrective to a simplistic view of the Soviets, especially under Stalin, as a bunch of fanatics. A few do populate these pages, but they appear as humourless rather than stupid, while Maisky and his protectors emerge as effective and pragmatic. At a time when diplomats tended to ignore the press, he was a pioneer of generating political pressure by manipulating public opinion, usually by leaking sensitive information, which he mostly received directly from British politicians instead of the spies you might expect.

Though a good historian might be more concise, the diaries are a fascinating read: tricks of diplomacy next to observations about wedding gifts; strategies for influencing British government decisions follow anecdotes of Britishness like a question from Lord Wakefield, ex-mayor of London: “You seem to have a man . . . Lenin . . . Is he really terribly clever?”