Mordecai Richler’s 5,000 books

From 2013: Jacob Richler on the preservation of a literary lion’s library

Will Lew

Share

In 2013, Jacob Richler wrote about his father’s work and the opening of the Mordecai Richler Reading Room at Concordia University:

On Nov. 28 in downtown Montreal, Concordia University will commemorate its most admired and learned dropout, with the opening of the Mordecai Richler Reading Room. The room’s donated contents include my father’s preferred desk, and thousands of the books, periodicals, papers and other personal effects that my mother, brothers and sisters, and I packed up at our sprawling country house on Lake Memphremagog in the Eastern Townships, when we bid the place adieu over Labour Day weekend, 2011.

Of his three residences, this was the place where my father undertook his most important later work. That began in 1979, some five years after he bought the place, when he headed to the cottage alone to get away from the distractions of Montreal and make a final, month-long push on Joshua Then and Now. The more demanding grind of Solomon Gursky Was Here made such country sojourns a habit.

By the nineties, his Montreal office had been relegated to fulfilling only the smallest jobs, like letters and newspaper columns. His annual six months in London yielded plenty of journalism. But the extremely serious business of writing very funny fiction had become almost entirely a cottage job.

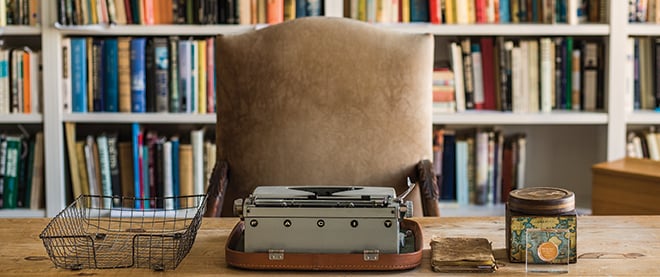

His top-floor office there was vast and airy, spread out behind an enormous picture window four frames wide that afforded a perfect vantage of the length of Sargent’s Bay. Had you seen it you would likely have assumed that the glorious view had much to do with the comfort and serenity he found working there. But really it was about the peace and quiet. The view was secondary. A closer look at the place revealed that his desk faced away from the window; when his gaze lifted from his typewriter he saw only a wall of books.

It was the issue of what to do with all those books that started the ball rolling on my family’s donation to Concordia. For, over his quarter-century in that house, my father accumulated rather a lot of them.

For starters he had brought along a small selection from his original English library, transported with the rest of our goods from London when we moved from there to Montreal in 1972. Therein were such items as his cloth-bound set of the complete works of Balzac, and his treasured, unabridged OED, a birthday gift from my mother that already spanned 12 massive volumes when she gave it to him in the late sixties—and had acquired innumerable supplements since.

Then there were all those books he bought for research and pleasure, and the hundreds of volumes sent as gifts from authors and other friends. But most were sent his way for review. Over his long tenure as a judge at the Book-of-the-Month Club, and later, as books columnist for GQ magazine, our mail never arrived through the slot in our front door. Instead, the postmen rang the doorbell and handed us our mail in bulging canvas Canada Post sacks, sometimes several at a time.

Over those years our country house gave every appearance of growing organically. For example, the kitchen widened. In fulfillment of one of my father’s childhood dreams a regulation-size snooker room sprouted from one side of the building. And from another wing, for my mother, Florence, there emerged a solarium full of hanging plants with a solitary chair for the quiet contemplation of poetry. But the one over-arching theme of purpose to all those clanging hammers and buzzing saws was actually this: more bookshelves.

New shelves filled out the basement. They wound their way through my mother’s new study and through her kitchen. They spread through the living room, framing the fireplace and staircase. They came to cover at least one wall in each of our bedrooms. They were installed to fill three massive walls of my father’s office—with a few stand-alone units in between. And as the coup de grâce, one summer when my brother Noah went away on an ill-timed trip, my father annexed his bedroom, had the wall that separated it from the neighbouring study removed, lined both rooms with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and created a library in their place.

That library came to be filled almost exclusively with fiction. Biographies resided next door on the shelves of the living room. Poetry was filed in my parents’ bedroom, along with the rest of my mother’s literature. Non-fiction in my mother’s fields of cooking and gardening stayed in her kitchen and study. Non-fiction that touched on any subject of my father’s favoured research (Judaica, Canadiana, Hollywood, sport, swinging London, Northern exploration, the occult, and so on) all went upstairs to his office, along with myriad editions of his own books. And once those shelves were full, my father expanded his stacks into the shelves of all remaining bedrooms, loading my sister Emma’s shelves with books on military history and the Second World War, my sister Martha’s with volumes on art, and mine with travel.

Growing up—and later, holidaying—amidst all these books was immeasurably enriching. But packing them up once our house was sold was an altogether different matter. I thought that the expedient thing for my mother to do would be to take a page from one of those great contests that pop radio stations used to run at record stores back in the eighties, and let her five children loose in the house with our own shopping carts and 90 seconds to grab what we could. But—alas—she was adamant that my father’s library be preserved intact.

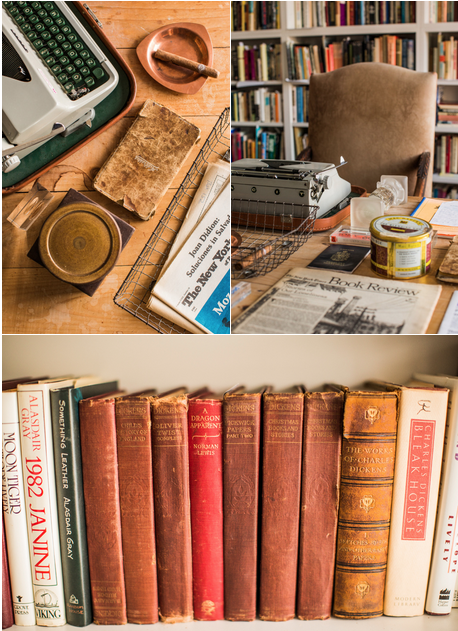

She also wanted it presented in a way that amounted to some sort of permanent monument to his favourite workspace—through inclusion of select papers, and in particular, his favourite desk. Not the beautiful antique roll top she had found him at a Montreal auction—oak, with bird’s-eye maple inserts (and lightly charred on one side, from the time when while talking on the telephone he accidentally set fire to his just-completed typescript of Joshua Then and Now with a mishandled cigar). His favourite desk was his country desk, fashioned makeshift by the cottage handyman from planks of unfinished pine. The desk on which he wrote Joshua Then and Now, Solomon Gursksy and Barney’s Version.

Lastly, my mother wanted the collection to remain in Montreal. And as McGill declined the opportunity, Concordia was the obvious choice. Appropriate, too, as my father had attended its precursor, Sir George Williams University, for two years in the late forties, before quitting school and Montreal to head to Europe to get started.

Concordia has designated adjoining rooms of a combined 65 sq. m for the purpose. My father’s tea-stained desk will be on permanent display, along with one of his old typewriters and other items transplanted from his office. The space is not adequate for displaying the entire collection we made available, of 157 boxes containing 5,000-odd books, and sheaths of typescripts and personal papers. But all this has been inventoried, and most will be accessible.

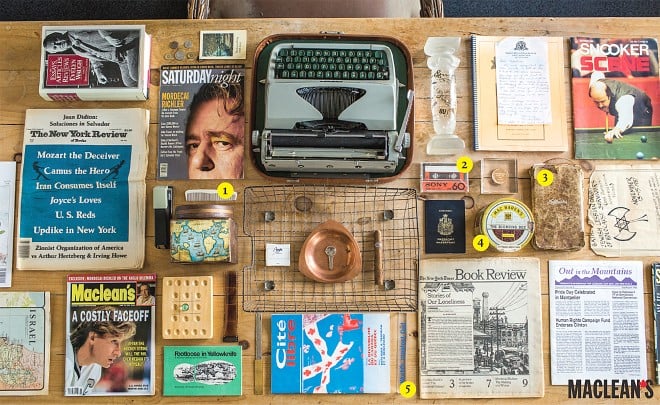

For example, consider the following partial list of the contents of Box 29:

Book: The Essays, Articles and Reviews of Evelyn Waugh.

Pamphlet: “Footloose in Yellowknife”

Magazines: Saturday Night, Maclean’s, Signature, The New Yorker, The Oldie, Cité Libre, Snooker Scene, Equinox, The Paris Review and Climax: The Journal of Sexual Perfection

Giller prize sculpture

Periodicals: The New York Review of Books, the New York Times Book Review, Out in the Mountains, Vermont’s newspaper for lesbians, gay men and bisexuals.

Paper flyer: “Gathering Jewish Lesbian Daughters of Holocaust Survivors”

Baltic Shipping Company menu for Aleksandr Pushkin, notes by MR on the back

I will be tracking that last one down at the first opportunity, as I have never seen it before and want to know what the notes say. Although, sight unseen, I know they will not include phrases like, “sated, again,” or “enough with the Beluga, already.”

The Soviet ocean liner Aleksandr Pushkin was the ship on which my parents booked our transatlantic passage when, in the summer of 1972, they moved us from London to Montreal. My father bought first-class tickets—but once aboard, was promptly informed that Soviet ships had only one class. Not quite true: each night the crew could be observed enjoying themselves, ensconced behind a glass partition in what would have been the first-class dining room, scoffing all the vodka and caviar that my father had wistfully planned on.

The crew also availed themselves of all my father’s whisky and champagne, draining the bottles somewhere on the short trip from docks to cabin. But at least they did not get their hands on his books—because my father had left almost all of them behind in London, dividing them up between a few friends and acquaintances for safekeeping until his probable return. Alas, he never saw any of those books again.

“Don’t lend books—you’ll never see them again,” he always told me.

Which I suppose could be seen as another reason why his collection grew so large. And why it’s a good thing that the Richler Reading Room is most definitely not going to be a lending library.