PTSD and the loneliness of coming home

Author Sebastian Junger asks what if PTSD is located not in the trauma of combat, but in the transition back to modern life?

Canadian Forces Syria. August 18, 2015. (Canadian Forces)

Share

The article was originally published on May 30, 2016

Sebastian Junger wants to talk about a paradox. U.S. combat mortality rates have been dropping exponentially for 70 years while disability claims have skyrocketed. The 21st-century army suffers deaths at only a third of the rate of its Vietnam-era predecessor, but files for disability three times more often than Vietnam vets. In part, the opposing trends are entirely predictable: medical advances mean severely wounded soldiers survive more often but are in need of life-long care. But it’s the nature of the claims that preoccupies Junger. The American military currently has the highest reported post-traumatic stress disorder rate in its history—probably, Junger reckons, the highest in the world. Roughly half of Iraq and Afghanistan war vets have applied for permanent PTSD disability. Yet combat troops make up only 10 per cent of the army, the prominent journalist adds in an interview, “so the remaining 40 per cent has to be explained by something other than trauma” in combat.

That something else, Junger argues in 2016’s Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, lies in the psychological shock American vets encounter at home, rooted in the vast gulf between the essentially tribal nature of war and modern, individualistic societies. Contemporary culture’s failure to properly reintegrate those who suffer danger and trauma on its account—not just soldiers but emergency personnel and others—is not a matter of misapplied funding or mental health care, but of modernity’s inability to offer a communal bond that matches the veterans’ intense experiences. Humans don’t mind hardship, Junger writes, as much as they mind feeling useless, and “modern society has perfected the art of making people not feel necessary.”

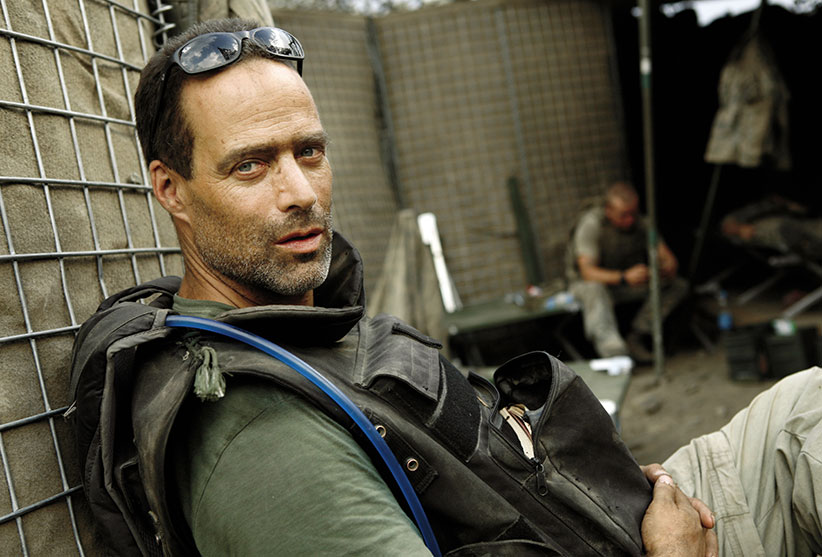

Junger, 54, is still most famous for The Perfect Storm, his 1997 bestseller about Massachusetts fishermen lost at sea, but since then his focus has been on men at war, in the award-winning documentary films Restrepo and Korengal and his book War (2010), all dealing with Afghanistan. Pondering the PTSD claims and his own experiences—including a brief bout of PTSD after he first returned to America in 2000 from Afghanistan, where he was “embedded” with an Afghan leader—have led him to the most personal book of his career. Tribe is framed by an event that has remained alive in his memory for 30 years. Hitchhiking outside Gillette, Wyo., in 1986, Junger watched as a dishevelled man walked up the on-ramp from town toward him. The visitor asked Junger if he had any food; fearing robbery, Junger lied and said he didn’t. The older man, who explained he lived in a broken-down car in Gillette and had seen Junger pass by, gave the author, then 24 years old, the lunch a local church had provided him: “Just wanted to make sure you were okay.”

If home is where they have to take you in, Junger now reasons, then tribe may well be defined as “people you feel compelled to share the last of your food with. I don’t know why that man put me in his tribe, why he took responsibility for me, but it was a life-long lesson in generosity.”

In Tribe, Junger combines those lessons with not-entirely-random historical facts: the way defection along colonial North America’s ever-roiling frontier virtually always went from European to Native; how crime dropped in post-9/11 New York and mental health indicators improved during the London Blitz. He filters them all through the PTSD epidemic, which he uses as a “lens to look at the failures of modern life.” The result is jarring, thought-provoking and politically resonant all at once.

Junger does not mean to romanticize tribal life, certainly not the endemic warfare, torture and violent death that was as prevalent between Native groups as it was in European-Native conflict. (He’s descended from a woman who hid with her baby boy—his ancestor—in a cornfield in western Pennsylvania in 1781 while a raiding party killed her older sons.) But he does want readers to consider its virtues—the way a million years of hominid evolution has suited us to it, psychologically and emotionally—much as colonial-era thinkers did. Benjamin Franklin was not the only one to question why Native children “brought up among us and habituated to our customs” fled to the wilderness at the first opportunity, or why white captives, ransomed home by relatives, also tended to run back.

Sometimes observers in racially stratified colonies acknowledged the Native indifference to skin tone as a factor, how white members were accepted as tribal equals in a way Native children rarely were among settlers. For European female captives, whose even greater tendency to prefer Native life troubled colonists, the advantages went further. “I am the equal of all the women in the tribe,” one white woman told a French official. “I shall marry if I wish and be unmarried again when I wish. Is there a single woman as independent as I in your cities?”

Tribalism’s inherent egalitarianism, its place for everyone in war and peace, compares favourably with modern culture’s atomism, argues Junger. Social resilience, as it is known, is a better predictor of trauma recovery, according to studies cited by Junger, than individual resilience. Soldiers find this emotional support, at tribal-level intensity, in a military unit’s cohesion, and they miss it achingly when they return home. “Part of the trauma of war is leaving it,” he writes.

Although soldiers in all First World armies returning from danger zones face the same struggles in reintegrating—a 2015 Canadian Forces study found that deployment abroad was emerging as a significant risk factor in military suicides—Junger thinks Americans face a country of exceptionally low social resilience. Inequality is growing and jobs hard to find: “Instead of being able to work and contribute to society—a highly therapeutic thing—a large percentage of vets are just offered lifetime disability payments.”

Junger’s constant circling back to the disability response is one of the factors that make Tribe impossible to read without the U.S. presidential election looming in the background. That’s true even though Junger wasn’t thinking about the age of Trump, a rough beast not yet born, when he ended his book with a reference to “this extraordinary moment in history.” (That was a nod to a more cosmic conjunction—how a species still Stone Age in its psychological and emotional impulses is on the verge of “space travel and AI.”)

But the constituency Donald Trump claims to speak for—a distressed, primarily white, working class wracked by economic uncertainty, widespread drug abuse and shrinking lifespans—provides the great majority of the 10 million American civilians on disability. As with U.S. military disability claims, the overall American rate is the highest in the First World, 9.2 per cent to the OECD average of 6.7. Disability payments, which run to more than US$200 billion yearly, are at the heart of both American conservatives’ demand for entitlement reform and Republican voters’ embrace of Trump, who has promised to preserve them. Junger—who cares far less about cost than how the label “disabled” is too often a marker of bought-off victimhood and a certification of uselessness—picks no side. But he does think the issue is a key factor in the way “what has always held us together before is breaking, and all our basic conflicts are coming to a head.” The American super-tribe, Junger fears, is dissolving into its constituent tribes, none of which seem inclined to share the last of its food with the others.