No, Hillary Clinton should not ‘Shut the F–k Up and Go Away’

Anne Kingston: Clinton’s new book shows she emphatically refuses to do so—and might be her most important political legacy.

Democratic presidential nominee former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton speaks during a campaign rally at Pasco-Hernando State College East Campus on November 1, 2016 in Dade City, Florida. With one week to go until election day, Hillary Clinton is campaigning in Florida. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Share

How history will treat Hillary Clinton, we cannot know. But the fact so many people—across the political spectrum—want to silence her, to degrade her, to shove her off the public stage, offers a chilling snapshot of the here and now. “What’s to be done with Hillary Clinton, the woman who won’t go away?” fretted The New York Times. “Former Clinton Fundraiser Says Hillary Should ‘Shut The F–k Up And Go Away,’ ” the Daily Caller announced. Vanity Fair was only slightly more polite: “Can Hillary Clinton Please Go Quietly into the Night?” Even progressives’ progressive Bernie Sanders, promoting his new book on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, urged the nation “to go forward, not backward,” when conversation turned to Clinton’s upcoming book. It’s “silly to rethink the 2016 election,” Sanders said. The barrage brings to mind two chestnuts: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” and “déjà vu all over again.”

It’s not been a year since an unqualified, undisciplined, misogynistic, serial liar was elected U.S. president. Donald Trump has diminished the nation’s standing internationally, abetted white supremacists, degraded the democratic process, tweeted threat of nuclear attack, and appears to have colluded with the Russian government. And yet somehow Hillary Clinton, regarded by many as the most qualified presidential candidate in U.S. history and a role model to generations of women, remains the nation’s paramount problem. Have these people learned nothing about false equivalencies? At a time civil liberties and women’s rights are under daily attack in the U.S., it’s worth remembering that democracies don’t erase history. Autocracies do.

READ MORE: ‘You’ve got to hand it to Trump’, and other quotes from Clinton’s new book

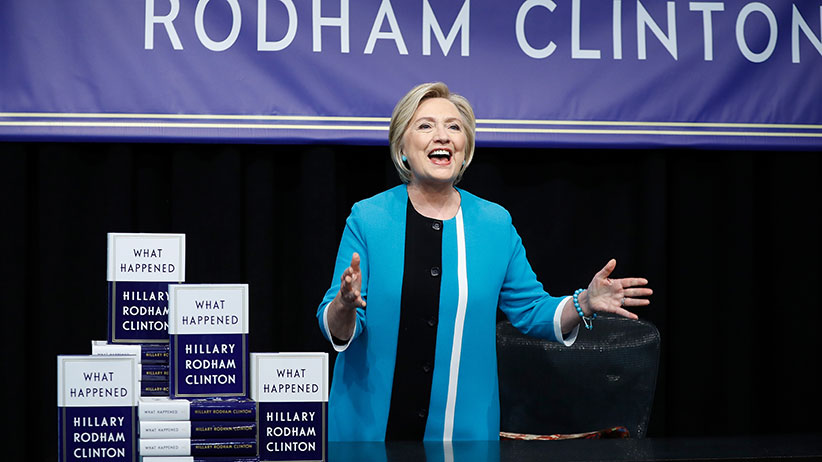

Clinton’s new book, What Happened, released Tuesday, has met with the polarized response that punctuated the ugliest, most riveting election campaign in American history. At 464 pages, it’s a workhorse—part memoir, part political post-mortem, part policy primer, part blueprint for the future. Lessons from 2016 can “help us heal our democracy and protect it in the future,” Clinton writes.

READ MORE: Hillary finally talks: ‘As an American, I’m pretty worried’

What Happened presents the former political insider and policy wonk as outraged, concerned citizen. The Trump administration is a “full-on ideological assault on the legacy of the Great Society and of the New Deal,” Clinton writes; “there are times when all I want to do is scream into a pillow.” Throughout, she displays a wry humour unseen on the hustings. Trump gets no mercy; he “dreams of Moscow on the Potomac,” she writes at one point.

The book begins with Clinton’s interior monologue during Trump’s inauguration. She debated going. When there, she fantasized about where she’d rather be: “Bali, maybe? Bali would be good.” She recalls sharing a rueful glance with Michelle Obama that read, “Can you believe this?” she writes. When Trump declared his intention to run in 2015, she thought it was a joke, having watched the businessman transition from “tabloid scoundrel to right-wing crank.” Then she watched him receive wall-to-wall media coverage: “The joke, it turned out, was on us.”

Now-ominous foreshadowing was evident in a satirical video Clinton made for the 2006 New York State political correspondents’ dinner when she was a senator, she writes. In it, she posed as a wax figure, as well-known New Yorkers walked by commenting about her. One was Trump, who said: “You look really great. Unbelievable. The hair is magnificent. The face is beautiful. You know, I really think you should run for president.” When the camera panned back, viewers saw him looking into a mirror. “It was funny at the time,” Clinton reports.

Losing came as a shock from which the author still appears to be reeling (she was so confident she’d win that she and her husband bought the house next door to their Chappaqua, N.Y., home to accommodate a president’s big team). Yoga, supportive friends and Broadway shows helped her through the darkest days: “I also drank my share of Chardonnay.”

Clinton is clearly writing for history, using the platform to tell her version and correct the record—as well as the flagrant falsehoods that have taken grip. At times it feels like she’s still campaigning. She runs through her various policy positions—her economic plan, gun control, reproductive rights—that weren’t given fair airing, she says; she quotes a concerning stat from one Harvard study that found only 10 per cent of media coverage dealt with policy.

Clinton, clearly thinking legacy, works to remind readers that, contrary to her “establishment” label, she was a longtime activist, work that included going undercover in Alabama in the ’70s to expose segregated schools trying to evade integration. She also reminds readers that Sanders’s plan for improving the Affordable Care Act embraces the same approach she proposed.

Clinton rebukes the litany of insults hurled at her—from “Crooked Hillary” to the “Antichrist” to being “unlikeable,” a label that hurt her, she writes. On the latter score, much of What Happened presents as a loving, compassionate, engaged mother, daughter, wife, grandmother—and the kind of boss who frets over staff wearing sunscreen. The narrative comes alive when Clinton writes of her engagement with groups such as “Mothers of the Movement,” whose members have lost children to gun violence.

Clinton, raised to believe marshalling facts and being prepared will win the day, wasn’t equipped for an emerging political reality that saw voters care less about what politicians say than how they make them feel—and bought into wild conspiracy theories, including such insanity that her campaign and ISIS were funded by the same source or that she was running a child-sex ring out of a pizza parlour. “I was running a traditional presidential campaign with carefully thought-out policies and painfully-built coalitions, while Trump was running a reality TV show that expertly and relentlessly stoked America’s anger and resentment,” she writes.

An old-school liberal proponent of changing the system from within, she was similarly perplexed watching Bernie Sanders build a grassroots progressive movement with plans that were “little more than a pipe dream.” She waited for a reality check that never came: “In previous elections, there was always a moment where candidates had to show they were serious and their plans were credible. Not this time.” In 2016, she writes, change in America “meant handing a lit match to a pyromaniac.”

Throughout, Clinton offers glimpses of what might have been. She contrasts her plans for her first 100 days with what happened. (Him: Muslim ban, failure to build the Wall. Her: jobs and infrastructure package funded by raising taxes on the richest Americans, push for comprehensive immigration reform with a path to citizenship.) She shares the ending of her unread victory speech—a touching tribute to her late mother.

RELATED: How Hillary turned the U.S. election into a showdown over gender

What Happened delivers the mea culpas many Clinton critics want, though it’s unlikely they’ll be satisfied. “You can blame the data, blame the message, blame anything you want—but I was the candidate. It was my campaign,” she writes. Yet she tries to put it in context. Using a personal email server when secretary of state was a “boneheaded mistake turned into a campaign-defying and destroying scandal,” she writes, pointing out the email paradox: when people read her emails, they tended to like her—her concern for others, her behind the scenes acts of kindness.

“What happened”—i.e. “Why she lost”—is a complex amalgam, Clinton writes. The “damned emails” get a chapter, as does Russian intervention, “Trolls, Bots, Fake News, and Real Russians.” Her obsessive tracking of timelines and details made her feel like Carrie Mathison on Homeland, Clinton jokes.

Other factors played a role, she insists, including a global populist wave and the historical challenges of being a third-term Democratic president. She lost “partly because I’m a woman,” she argues, citing historic male domination of the public sphere. As the first female candidate to run for president for a major political party, she had to figure out how to navigate what has traditionally been a masculinity contest: “I had no precedent to follow; and voters had no historical frame of reference to draw upon.”

Personal narrative is vital in politics, Clinton points out, admitting, “I never figured out how to tell the story right.” She didn’t exploit what qualified her for the job: trailblazing through many “firsts”—first female partner at her law firm, to the first first lady elected to office. “I didn’t want women to see me as ‘the woman candidate’ but ‘the best candidate.’ ” But stories also need a receptive audience, she notes: “I wasn’t sure the American electorate was receptive to this one.”

Polls didn’t get it wrong, Clinton claims (she did win the popular vote, she likes to remind the reader). Rather, “something important and ultimately decisive happened at the very end.” That would be the FBI director announcing the probe into her emails was being reopened 11 days before the election—the “Comey Effect.” It turned the “picture upside down,” Clinton writes, creating fear her presidency would be beset by investigations, even impeachment. Oh, the irony.

That Clinton refuses to play the fall gal is also destined to infuriate her critics. “If it’s all my fault, then the media doesn’t need to do any soul-searching,” she writes. “Republicans can say that Putin’s meddling had no consequences. Democrats don’t need to question their own assumptions and perceptions. Everyone can just move on.”

She has a point. If Trump tapped the politics of anger and resentment, Clinton, a woman and consummate political insider, become the repository for it. Far easier to blame her failures—her perceived if unproven corruption, her “unlikability,” her entitlement—than to look squarely at the wellspring of misogyny and double standards her campaign faced. It puts the onus on her, not us.

Lest anyone forget those double standards, Clinton itemizes a long list that includes the outrage over an image of comedian Kathy Griffin holding up Trump’s severed head versus the radio silence over t-shirts sold at the Republican National Convention bearing an image of Trump holding up Clinton head.

Clinton doesn’t spend a lot of time on “what ifs,” though it’s clear that anyone with her obsession for detail and facts has likely done countless rewinds. One of the most publicized excerpts from the book showed her second-guessing her reaction to Trump when he loomed over her in the third presidential debate, just after news of the Access Hollywood tape broke. “My skin crawled,” she writes. “It was one of those moments where you wish you could hit pause and ask everyone watching, well, what would you do? Do you stay calm, keep smiling and carry on as if he weren’t repeatedly invading your space? Or do you turn, look him in the eye and say loudly and clearly, ‘Back up you creep, get away from me?’ ”

Option B would have made for better TV, she writes. “Maybe I have overlearned the lesson of staying calm, biting my tongue, digging my fingernails into a clenched fist, smiling all the while determined to present a composed face to the world.” That paradoxically is the authentic Hillary Clinton, respectful of political tradition and hyper-sensitive to how she appears, conditioned by a lifetime of criticism.

The last chapter sees her make a pilgrimage to Eleanor Roosevelt’s cottage in Hyde Park, N.Y. The outspoken former first lady and activist, one of Clinton’s heroes, also endured vitriolic backlash more than half a century ago, she notes. An FBI director put together a 3,000-page file on her. Clinton quotes a columnist who wanted Roosevelt silenced: “her withdrawal from public life would be a fine public service.” “Sound familiar?” Clinton asks.

She’s not going anywhere, she writes. She has formed a new initiative, “Onward Together,” with the motto “Resist, insist, persist, enlist.” In her book, Clinton quotes Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s oft-repeated “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” If she learned one lesson from an historic, hateful campaign, clearly it’s that. Which is why refusing to shut up now might well be Hillary Clinton’s most important political legacy.