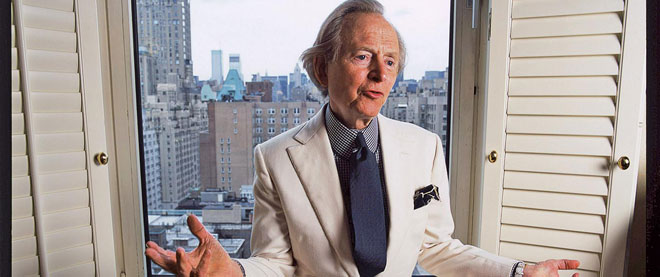

Tom Wolfe on how he wrote ‘Back to Blood’ in 2012

The writer and journalist on being recognized at a Miami strip club and inventing punctuation

David Corio/Redferns/GETTY IMAGES

Share

At 81, Tom Wolfe is still an ardently curious writer. To research his new novel, Back to Blood (for which he switched publishers and earned a reported $7-million advance), he talked to a cross-section of Miami society, from recent Cuban immigrants to hedonistic WASP-y types. The result is a lurid 700-page account of sex, money, art, and what he calls “the general clash of ethnic groups, racial groups and nationalities.”

Like his books, which include examples of new journalism such as The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as well as big novels like The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe’s conversation is wide-ranging, digressive and as zippy as his prose.

Q: When you conceived of Back to Blood, did a part of you say, “I’d like to spend some time in Miami—it’s quite nice there in the winter?”

A: Ha ha! I hadn’t thought of that, but I did come at the right time. When it’s hot in Miami, it’s good and hot. I took maybe 12 trips there working on this.

Q: Did you blend in there with your trademark white suit?

A: I didn’t wear a white suit—I never do when I’m doing some reporting. But I stood out anyway because I had a necktie on. Hey, are neckties fewer and fewer in Canada? Here, there are so many people not wearing neckties, but they’re wearing shirts that were made for neckties, so you see all these buttonholes, the extra material. I’ve been wanting to do a favour for the country by trying to design a shirt that was obviously not made for a necktie.

Q: In Miami, your fixer, Oscar Corral, was filming you for his documentary, Tom Wolfe Goes Back to Blood. How did it change your fact-gathering to have someone there with a camera?

A: I told Oscar at the beginning, there are some interviews in which the presence of the camera is just not going to work. So in his documentary were [scenes] that were not in themselves sensitive. At the Columbus Day Regatta, there was a group of kids on a deck that was fairly high off the water, and they started cannonballing me—it makes a big splash. It makes a good movie, too, just seeing me in what, to a lot of people, would seem very esoteric circumstances.

Q: I’ve read that you were recognized by the manager when you went on a research trip to a strip club. How did that feel?

A: Actually this was a bouncer, a great big guy. I’d shaken the hands of about five girls by then—only they don’t shake hands; their greeting is to clasp you on the inside of the thigh. Very friendly. I had on a necktie; I guess nobody else did in the whole place. I don’t think there was another blue blazer in there, come to think of it. Anyway, [the bouncer] says, “You’re Tom Wolfe!” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Oh wow! Wait’ll I tell people this—Tom Wolfe is at a strip club.” So I immediately said, “I’d like you to meet my friend Oscar Corral from the Miami Herald.” That kind of took the steam out of breaking the news.

Q: In the novel, the young reporter John Smith, who also tends to dress formally, goes to a strip club to investigate Russian criminals. Was he inspired by you?

A: Oh, I didn’t mean it to be so clear, but sure, I was pretty much like him. I didn’t really lose out on the playground the way he did, because I was an athlete, somewhat. But I think boys learn on the playground whether they’re going to order other people around or whether they’re going to take orders. Lots of people on the weak side of that equation are ambitious, like John Smith. It’s common for young people to be so determined to prove themselves that they end up doing things that the tough guys would never do. Many reporting assignments really are dangerous. I’ll never forget being caught in a crossfire at an apartment complex [between police and an armed criminal]. I saw my competitor from the Washington Star go through the police lines and he started creeping towards the complex. I thought, “Damn, I’d better do it too!” So I followed him, and the next thing you know, on both sides, there were fusillades, bullets that seemed like they were right over your head, and tremendous flashes of light. It’s very disorienting and a little bit frightening—that’s the kind of thing I would never have voluntarily done in my entire life. That was at the Washington Post, and I had the best job, I thought in retrospect, at the newspaper: I was a general assignment reporter. Now, in the U.S., so many publications are relying completely on freelancers.

Q: Do you feel it’s harder for journalists now to obtain the time and resources to craft the kind of long literary pieces that you were famous for writing?

A: When I was doing a lot of that, it was not by any means high-income work, but it was satisfying to me. Now it’s just not easy at all. The money is always a problem. There was a time in the 1930s when magazine writers could actually make a good living. The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s both had three short stories in each issue; these were usually entertaining, and people really went for them. But then television came along, and now, of course, information technology . . . the new way of killing time. It’s replaced knitting and things like that. Only in knitting, you’ve got a product at the end, and [with] informational technology you don’t. My God, the amount of time people waste just contacting one another just because they can! Facebook’s a very good example. When Mark Zuckerberg came to New York right before the IPO was to go into effect, that was the beginning of the rise of Silicon Valley as the new Wall Street, in the sense of the excitement, the money. New York’s in second place now.

Q: Even though Facebook’s stock prices fell considerably thereafter.

A: That happened because the IPO was handled by the old boys. Investment banks were the ones who screwed things up. And Zuckerberg wearing his T-shirt and hoodie—the old boys here could not imagine such a thing. “He looked so gross! How could you do business with someone like that?” He’s the new John Jacob Astor, the new E.H. Harriman, the new Henry Ford. His name will go on that list in the history text eventually. It’s not that he invented the technology—he just figured out a new way to hook people up with it. All those early people had products, whereas on Wall Street, there are no products, really.

Q: You have long been a well-known champion of realistic fiction, although parts of Back to Blood seem satirical, such as the orgy in the chapter about the Columbus Day Regatta. How does satire fit in with realism?

A: Well, first of all, I didn’t see everything that’s in that chapter, but I talked to people who had; I felt sure of my ground. Perhaps I brought in so many details that I concentrated the effect, but I think there were probably years when it was wilder than what I showed. I have never knowingly, I swear to God, written satire. The word connotes exaggeration of the foibles of mankind. To me, mankind just has foibles. You don’t have to push it! [laughs] When I wrote The Bonfire of the Vanities, there were many comments—“What a bleak picture of New York! What an exposé on the sordid soul of that city!” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, because I was in awe of the characters. [The book] was filled with wonder; I wasn’t trying to make a point, just as I’m not trying to make a point in Back to Blood—I have no agenda whatsoever. I just want to make the place come alive, because it’s unusual.

Q: Is your own inner monologue as excitable as those of your characters?

A: Oh yeah! People will complain about my exclamation points, but I honestly think that’s the way people think. I don’t think that people think in essays; it’s one exclamation point to another. And also I have a new device in this book: inner monologues are set between a row of six colons at the beginning and six colons at the end. I rather like that, if I may praise myself.

Q: There’s been quite a bit of talk about this book, for years, even. Do you still look forward to publication with anticipation?

A: Well, it’s more nervousness, to tell you the truth, because I have no idea what happens next. Everything that has been written about it so far has been written before anybody could possibly look at the product.

Q: Do you read your reviews?

A: Oh, I pretend to be like Arnold Bennett, the British novelist who was very popular in the ’20s and ’30s. He was considered a lightweight, so he didn’t get particularly good reviews. He would say, “I don’t read my reviews; I measure them!” But if they come to my attention, I’ll read them and I’ll suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune just like anybody else.

Q: Even if there are slings and arrows, it must be nice to feel that you can still get people riled up.

A: [laughs] Well, it proves you’re alive, anyway, doesn’t it!