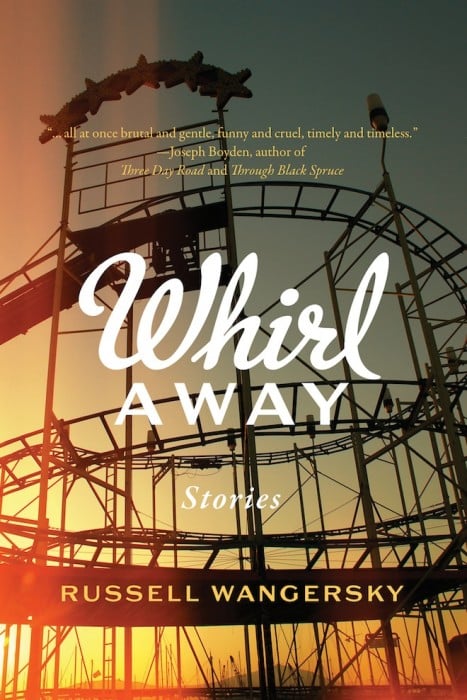

Giller Prize nominee Russell Wangersky on writing, and reading

Plus, an exclusive excerpt from his book of short stories, ‘Whirl Away’

Russell Wagnersky

Share

Born in Connecticut and raised in Nova Scotia, Russell Wangersky, 50, has been a Newfoundlander for three decades. When he was 14, Wangersky announced to his parents that he would become a great Canadian writer, since CanLit’s then-current luminaries—Robertson Davies, Margaret Atwood and W.O. Mitchell—were extremely old and liable to die soon. But he put that ambition on hold to work as a journalist (and volunteer firefighter) until 2001. Since then Wangersky has written a non-fiction book, a novel and two collections of short stories. His latest collection, Whirl Away, has been shortlisted for the 2012 Scotiabank Giller Prize. The short story is the literary form that comes most naturally to him, Wangersky says in an interview, because “you can hold the whole thing in your head, and know where you are when you’re at the end; in a novel, you can lose your place, your voice, your nuance.” That’s not something that happens in any of Whirl Away’s diamond-etched tales of characters who have slipped their moorings and floated off, consciously or otherwise, to disaster. Over the next few issues, Maclean’s will feature brief essays by all five Giller nominees, and excerpts from their books. Here is Russell Wangersky on writing (and reading), followed by an excerpt from Whirl Away’s “Bolt.”

I write in the kitchen, the evening rolling into night, and when I look out the window, I’m always aware of the group of St. John’s row houses behind my own. Their rooflines loom in the window, a dark, serious line, but the houses themselves lean the other way, threatening the sidewalks in front of them more than our small yard.

In a strange way, I’ve always thought of them as being like readers. Out there on the periphery looking in at me, not completely interested but not disinterested either. And I watch them back sometimes, imagine that they’re leaning closer tonight, and wonder if that lean is because I’ve finally sparked a little curiosity. Because, with everything else that happens in the big and busy world, I’m just trying to be heard.

It’s a funny business, writing. Listening all the time, grabbing small snatches of conversation from strangers and trying to winkle out what they mean, drawing up little worlds in my head and trying to put them down perfectly on paper, collapsing their dimensions. Trying my best to explain things that sometimes I’m not sure I understand fully myself.

I do that in my day job, too, writing editorials and columns.

Always explaining what I know, what I think, what I imagine.

There are plenty just like me, far more than you know: writers working with little fanfare through late nights on top of everything else they do in the day, making time to work and brazenly stealing the hours they can’t make.

So I thought I would try to explain something about us for a change: what we really want is someone to read us. To hear what we’re saying.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a book that did not leave me with some particular thing— they don’t have to be on prize lists to have a marvellous turn of phrase, a particularly vivid character or a thin sliver of pain as sharp as a splinter. I get to read a lot: my office is a war zone of books, and I value them all, even the ones with fatal flaws.

At the same time, I don’t think I’ve ever written anything that I didn’t believe sent a careful message out there, a lighthouse seeking some kind of receptive vessel on the sea.

What am I saying?

Perhaps that we should read shortlisted books. Read long-listed books. But also that we should read far, far more than that, casting our lines out into a big country rich with big and varied voices. You would be surprised how much value there is in this country’s writers, and how close they are to you—how they can be right next door, both physically and spiritually.

I sit in the near-dark in one small pool of lamplight and imagine that, hope that, somewhere in that line of row houses, someone is listening.

I’m far, far from the only one. So lean in.

The bolt came through the open back window of the truck. It came in end over end. From a distance, if anyone had been watching it, concentrating, it might actually have appeared that the truck was doing the tumbling, and that the bolt was flying perfectly straight.

Just a rusty bolt John had found in the driveway, a bolt that he’d tossed in the back of the pickup with the duffle bags and the mitre saw and the rest of his stuff.

He didn’t hear the bolt whisper as it spun, the rushing air whistling along the even gaps of the threads; he had his hands full trying to figure out just what was happening to the pickup as it cut through the bright pink flowering fireweed, the truck leaving a four-wheeled, mown trail behind it, the wheels throwing up grass and mud and the petals of the flowers.

The bolt caught him in the curve at the back of his skull, at the midline and just below his hair, hitting that smooth dent where a lover might rest the heel of her hand. John had a brief moment to think about what-if—what if he hadn’t reached across the seat toward the glove compartment, what if he hadn’t over-corrected when the wheels touched the shoulder. He didn’t even get to “What if I hadn’t put the bolt in the back?” or more importantly, “Why did it fly so straight?” or “What are the chances of that happening?”

The bolt was still moving at close to a hundred kilometres an hour, the same speed the truck had been going before the front end smashed nose first into the bank. John, safely held in the grasp of the seat belt, had slowed as quickly as the truck had. He didn’t feel the bolt hit.

John, for once, didn’t feel anything at all.

The truck ended up on its roof, one wheel crookedly spinning long after the other three had stopped, and no one noticed the wreck until the next morning. Then a long-haul driver, riding high up in the cab of his Freightliner, saw the rusting bottom of the chassis standing out against the green and pink of the fireweed, rectangular and ochre and perched on the edge of a small peaty stream. There was already cold dew on the windshield when the driver waded down through the high plants to look through the window on the driver’s side.

“John was coming home,” Bev said.

“No, he wasn’t.”

“Yes he was, bitch. He was on his way here when he crashed. He was coming home for good. Why do you think he had all his stuff?”

“You’re lying.” Anne said the words quickly, as if saying them could force the doubt away, but she heard the tremble in her own voice—and she hated herself for betraying that feeling, even slightly. Because she hadn’t known where he was going. Sleeping, caught up in the false, warm security of comforter, sheets and pillow, she hadn’t even realized he had left.

They were speaking in undertones, barely more than hissing the words, aware that there were other people in the funeral home but focused on each other. Outside, the sun had come out around a huge grey bank of cloud, and individual shafts of sunlight were sifting down onto the surface of Bay Bulls, lighting irregular, ragged patches of ocean as if the light actually meant to single something out amongst the choppy grey waves.

Bev was small and blond and strangely angular. She gave the sense of always having her elbows in close to her sides and her hands up high, as if spoiling for a fight. That, and she finished her sentences by pushing her face forwards, like she was punctuating her words with her chin, daring the other person to disagree. It was the sort of habit that some people found off-putting, as much of a shove as if she had reached out and pushed them with both hands palm-flat against their chest.

Whenever she saw Bev, whenever she spoke with the other woman, Anne was always left with the same disconcerting thought: just how had John ever ended up married to her? It made her wonder if there was some kind of hidden, underlying character flaw in him that she knew nothing about, or that she was trying to ignore.

When she asked John about it, after they’d moved in together, he would shrug. “I was young, okay?” he would say, as if that was excuse enough. “We were both young.”

But she found that hard to accept—trying to imagine how it was that someone as easygoing as John would choose to marry someone so abrasive. Other people offered up old sayings like “Opposites attract,” but Anne couldn’t see it.

“No, really,” she’d ask him. “How’d you even get in the same room with each other, let alone end up married?”

And John would do what he always did, pushing his hands through the hair at his temples, where it grew coarser and with slightly more curl than on the rest of his head. It was a motion that always dislodged flecks of fugitive sawdust from the day’s work with the sander or fine curls of shavings from the planer. There was always sawdust on him somewhere, Anne knew, fragrant small chips that gave him an unexpected air of solidity, the green of birch, the closer, sticky familiarity of pine—a smell that was as much him as any other. He’d push his hands through his hair once or twice every time, but it was a way of saying that he wouldn’t answer, that the conversation was done.

It was a signal that he was about to shut down. It was the one thing about him that she found infuriating—the ability to stop any discussion by withdrawing completely.

Excerpted from Whirl Away by Russell Wangersky. Copyright © Russell Wangersky, 2012. Excerpted by permission of Thomas Allen Publishers. All rights reserved.

THE 2012 SCOTIABANK GILLER PRIZE: Canada’s most distinguished literary prize awards $50,000 annually to the best Canadian novel or short-story collection published in English