Remembering beloved Canadian writer Richard B. Wright

A year ago, the author joyfully looked ahead to his golden anniversary and talked of how he always made up stories

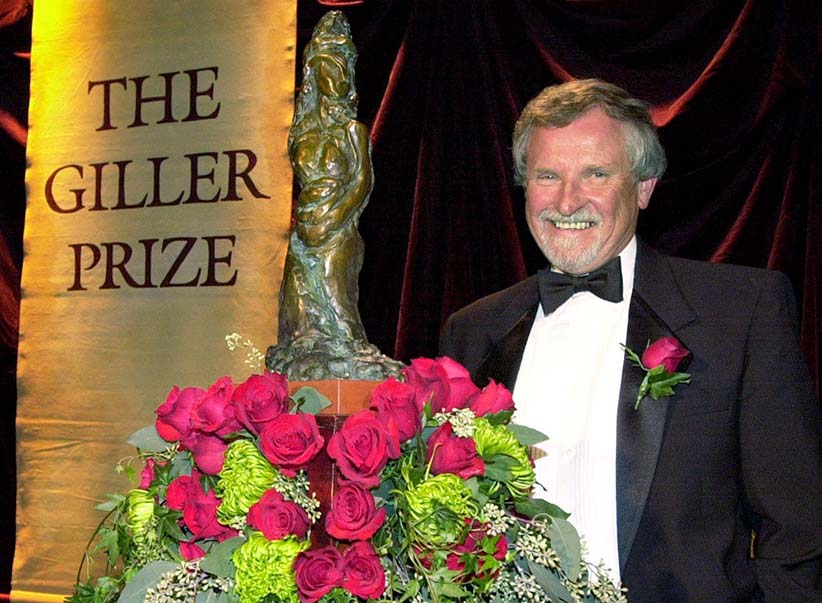

Author Richard B. Wright wins the 2001 Giller Prize for fiction in Toronto Tuesday November 6, 2001. (Aaron Harris/CP)

Share

Is it possible that author Richard B. Wright and his wife, Phyllis, have both passed away—Wright on Feb. 7 after a stroke earlier this month, and his wife last November from cancer? It was just a year ago that Wright, who lived in St. Catharines, Ont., was sitting in the lounge of Toronto’s King Edward Hotel, jubilant about plans for their golden anniversary in September, excited that friends and family would be joining them to celebrate.

“We’ve had a wonderful marriage,” Wright said. Then, smiling, he corrected himself: “We are having a wonderful marriage.” His wife Phyllis, an anglophone from the Gaspé region of Quebec, left home at 16 and moved to Toronto. The two met when they worked at Macmillan publishing in the 1960s. In 1966, they married and eventually had two sons. Wright said he considered her the perfect wife.

“Writers by and large are finicky,” he explained, “susceptible to depression and anxiety because of all of the uncertainty in their lives. (Phyllis) understood me. She gave me space when she thought I needed it.”

Wright, who was born in Midland, Ont. in 1937, first won literary acclaim in 1970 with The Weekend Man, a comic account of an alienated textbook salesman. But he was best known for his multiple award-winning novel of a Depression-era schoolteacher, Clara Callan. Through close observation of individual lives, Wright’s fiction replicated the coarse texture of human existence. His characters grappled with illness, violence, death and loss of faith; they sought meaning in literature, nature and intimate relationships.

Set in contemporary times, his final novel, Nightfall, contains flashbacks to the Gaspé in the summer of 1944. The story is a sequel to Wright’s novel October, in which widowed professor James Hillyer travels to England to comfort his daughter, who is diagnosed with cancer. There, he runs into an old acquaintance from that long-ago summer in the Gaspé, when both boys were in love with a feisty 15-year-old maid named Odette Huard.

Nightfall picks up the story two years later, in 2006, after the death of James’s daughter. Unable to shake his grief, James looks up Odette, now 77 years old. The novel examines the increasing significance of memory as we age, even as, paradoxically, it starts to fade or disappears altogether. Wright also hints at the mysterious relationship between memory and fiction: extended passages from the earlier novel are worked wholesale into the latter.

Wright, who was entering his 79th year, wanted to explore memory and its absence. In addition, he was eager to revisit the earlier book.

“I loved October,” he said. “There was something about it that really attracted me. I said to myself, I can still do something with this book. I wonder what Odette was like at 70?…What happened when she got on that truck (in Gaspé) and went back to Montreal? I just fell in love with her in a way that I sometimes do with certain characters. I did a bit of that with Clara Callan.”

Clara was the novel that made Wright a literary star, earning him a Giller, a Governor General’s and a Trillium Award. Among other things, the book famously exhibited the author’s uncanny ability to delineate the inner lives of women.

“Frankly,” said Wright. “I have always found women more interesting than men. They talk more about things that interest me. There’s not so much about golf and bowling as there is about feelings.

“And I always like that in my journey through life, the examination of my own feelings and trying to understand experience. For me, it’s the most important thing.”

From childhood, Wright was preoccupied with the question of “what life is really like” or “what life really is,” he recalled. Growing up during the war, he heard his parents discussing people whose sons had died. Even then, “I was wondering what they were feeling like when they lost that person and how they dealt with it—in my head. And then I extrapolated from that. Writing became natural to me because that’s what I was doing since I was eight or nine or 10. Only I wasn’t writing physically; I was writing in my head, making up stories.

“What I do is imagine people and make them come alive. It is emotional and intellectual in every way.”

Despite Wright’s extravagant gifts, writing never came easily. Ending a novel frequently presented a challenge. He might lie awake night after night, seeking a solution to a literary dilemma. Then the answer would suddenly come: “Bam!” said Wright. “You get a present from God. You just get what you’re looking for.

“There were times I remember when I finished a book and felt, this isn’t right; I’ve got to do more. And other times when I think I have what I want. Those are good memories for me.”

But his fondest memories, Wright said, involved vacations with his wife. “We’ve stayed in France a number of times. We rented an apartment just outside Mont Blanc on the Riviera and dealt with the locals and bought our groceries. I like the times we spent in England with our family. It is the time that I spent with my family that I cherish.”