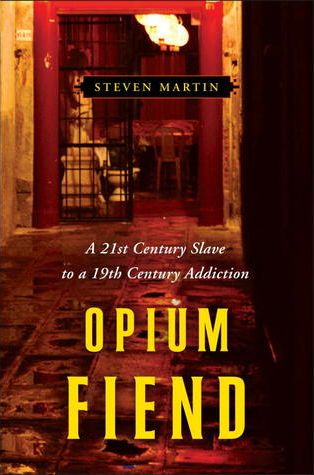

REVIEW: Opium fiend: A 21st-Century Slave to a 19th-Century Addiction

Book by Steven Martin

Share

In 1821, Thomas De Quincey published Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, a harrowing and subtly seductive account of his drug addiction. As a stylist, Martin is no De Quincey, but his story is just as wrenching. Born in San Diego and a compulsive collector since childhood, Martin worked as a freelance journalist in Southeast Asia, where he began collecting rare 19th-century opium-smoking paraphernalia—exquisitely crafted pipes and old lamps. Then he started using the equipment, at first recreationally, then falling into a 30-pipe-a-day nightmare habit that seemed unconquerable: reading Martin’s account of an unsuccessful attempt to quit in 2007 is like watching a high-speed car wreck unfold. Opium’s physical withdrawal symptoms are among the worst known, but that only makes them a match for the drug’s compelling mental effects, its ability to alter space and time and replace inner emptiness with profound, detached bliss. As user Jean Cocteau, quoted by Martin, remarked after describing life as an express train barrelling toward death, “To smoke opium is to get out of the train while it is still moving.” Martin was no match for poppy power.

In 1821, Thomas De Quincey published Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, a harrowing and subtly seductive account of his drug addiction. As a stylist, Martin is no De Quincey, but his story is just as wrenching. Born in San Diego and a compulsive collector since childhood, Martin worked as a freelance journalist in Southeast Asia, where he began collecting rare 19th-century opium-smoking paraphernalia—exquisitely crafted pipes and old lamps. Then he started using the equipment, at first recreationally, then falling into a 30-pipe-a-day nightmare habit that seemed unconquerable: reading Martin’s account of an unsuccessful attempt to quit in 2007 is like watching a high-speed car wreck unfold. Opium’s physical withdrawal symptoms are among the worst known, but that only makes them a match for the drug’s compelling mental effects, its ability to alter space and time and replace inner emptiness with profound, detached bliss. As user Jean Cocteau, quoted by Martin, remarked after describing life as an express train barrelling toward death, “To smoke opium is to get out of the train while it is still moving.” Martin was no match for poppy power.

And, of course, he is a romantic, or he would never have been drawn to opium in the first place. Everything about it, as reflected in his subtitle, carries echoes of the Victorian age. There’s the gas-lit literature, including Sherlock Holmes stories, and the historical associations, especially the Opium Wars, although Martin points out the British didn’t so much inflict opium on China as enforce its trade monopoly of a drug already well-established there. And then there’s the beautiful and thoroughly unmodern equipment—pipes, not syringes—that first attracted Martin, who argues convincingly that the driving hunger behind his collecting mania was intimately linked to his drug addiction.

Small wonder Martin’s story, as he writes, “lacks closure.” After taking the cure at a Buddhist monastery in Thailand, Martin’s abstinence remains “edgy,” and he comforts himself with thoughts that when health is lost to old age or disease, perhaps he can once again ride the magic carpet.