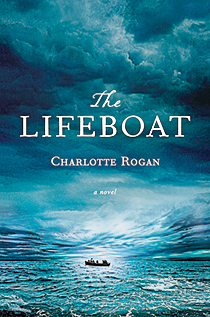

First-time novelist Charlotte Rogan found the inspiration for The Lifeboat in a 19th-century criminal case: two men stranded on a lifeboat were found guilty of murder for killing other passengers to save themselves. It’s a classic moral question, one you might have breezily explored in a high school ethics class: who do you toss out when the boat is sinking fast? Most of us will never have to answer that question (Survivor contestants don’t count). But Rogan’s story—an addictive read that’s over too soon—gets us awfully close.

First-time novelist Charlotte Rogan found the inspiration for The Lifeboat in a 19th-century criminal case: two men stranded on a lifeboat were found guilty of murder for killing other passengers to save themselves. It’s a classic moral question, one you might have breezily explored in a high school ethics class: who do you toss out when the boat is sinking fast? Most of us will never have to answer that question (Survivor contestants don’t count). But Rogan’s story—an addictive read that’s over too soon—gets us awfully close.

The book opens with 22-year-old Grace being charged with murder, and her lawyers suggesting she write down her side of things. Five days into a journey back to New York to escape the war breaking out in Europe in 1914, there is an explosion on board the ship. In the panic, Grace and 38 other passengers end up in a lifeboat, though not one that will hold them all for long. As the hours drift into days, and the hardtack and water run out, it isn’t long before, as Grace says, “the bare bones of our nature were showing.”

Loyalties in lifeboat No. 14 divide between one of the ship’s officers, Mr. Hardie, who keeps his charges in the boat and fights off other Empress passengers (wide-eyed, drowning children included) as they distance themselves from the sinking ship, and Mrs. Grant, an older, buttoned-up socialite who gains an air of moral superiority by vaguely suggesting more could have been done to save the others. Grace presents herself as a woman doing the best she can to make the right choices in an impossible situation. But she gives away hints of a ruthlessness of her own, including the details of how she came to secure her rich husband, and her spot on the lifeboat for that matter. After rescue arrives, it’s left to the lawyers to tease out whether anyone can be blamed for the death that brought Grace and two others to trial. When one of her co-defendants asks, “Is the only way we can prove our innocence by drowning?” Grace astutely suggests that perhaps a person cannot be both alive and innocent.