Rogers Writers’ Trust: Spotlight on John Vaillant

We asked everyone shortlisted for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize: Would you change something about one of your books after it was published?

Share

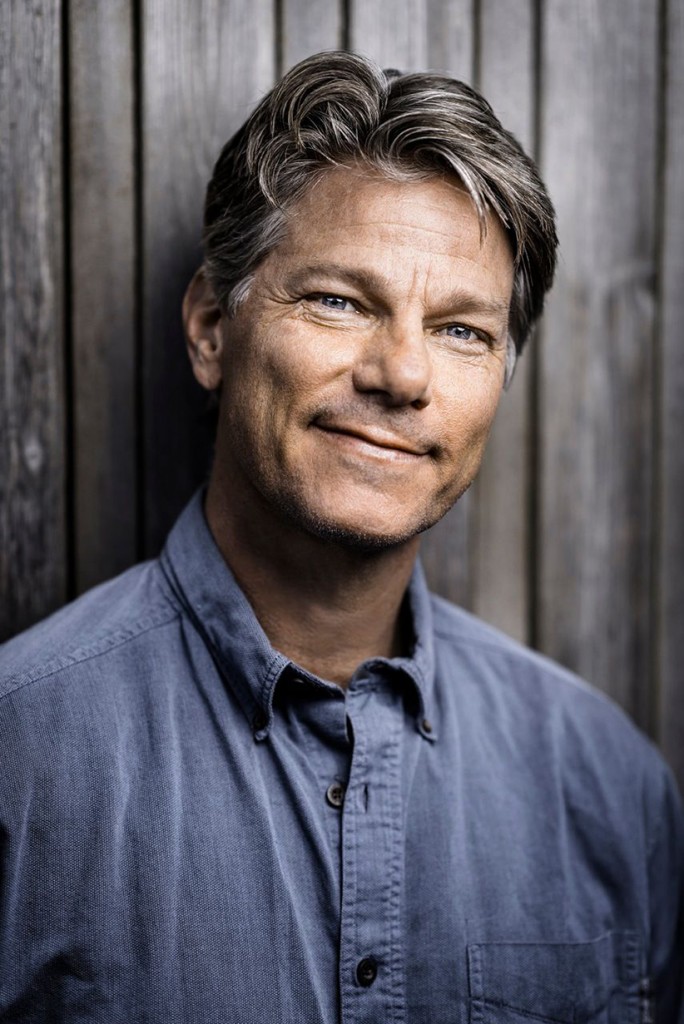

John Vaillant is nominated for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for his novel The Jaguar’s Children. The winner will be announced at the Writers’ Trust Awards ceremony in Toronto on November 3. The winner receives $25,000. Each nominee receives $2,500. Every day until the winner is announced, Maclean’s will publish an excerpt from each shortlisted writer, along with their answer to this one question: Have you ever wished you could change something (whether significant or small) about one of your books after it was published? Here is Vaillaint’s response, and here are other responses from other authors.

While my weaker self has wanted to tinker with lines after the fact, I truly feel there is no room for regret on a multi-year project like a book. The beauty of this medium is that you have the luxury of time to sit with, and field test, your work. You can look at individual lines or entire sections months – or even years – later and see if they still ring true. You also have an opportunity (arguably, an obligation) to get second opinions from friends, family and editors. If a tone-deaf line, or an indulgent scene survives that gauntlet of eyes and time, it’s on you, and you have to chalk it up to the process: you’ve made a sand painting and your hand shook, or your attention wandered, and now it’s a part of the work, and the record, to stand or fail the test of time.

The following is excerpted from The Jaguar’s Children. Copyright © 2015 John Vaillant. Published by Vintage Canada, which is a division of Penguin Random House of Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

AnniMac, if you get these messages and come to look for us what you are looking for is a water truck — an old Dina. The tank is a big one — ten thousand liters and you will know it when you see an adobe-color truck that says on the side AGUA PARA USO HUMANO — Water for Human Use. But that doesn’t mean you can drink it. This one is different because someone has painted J and R so it says now JAGUAR PARA USO HUMANO. I saw this in the garage before we loaded and I didn’t know if it was graffiti or some kind of code, the secret language of coyotes, but then I was nervous to ask and later it was too late.

Some things you want to know about coyotes — just like in the wild nature there are no fat ones and no old ones. They are young machos hoping one day to be something more — a heavy, a real chingón. But first they must do this thing — this taking across the border, and this is where they learn to be hard. Coyotes have another name also. Polleros. A pollero is a man who herds the chickens. There is no such thing really because chickens go where they want, but this is the name for these men. And we — the ones who want to cross — are the pollos. Maybe you know pollo is not a chicken running in the yard — gallina is the name for that. Pollo is chicken cooked on a plate — a dinner for coyotes. This is who is speaking to you now.

Besides me and César in here are thirteen others — nine men and four women, all of us from the south. Two are even from Nicaragua. I don’t know how they can pay unless they are pandilleros because it is expensive to be in here. To fit us all in, a mechanic with a torch cut a hole in the belly of the tank. Then we climbed in, and with a welder he closed the hole again and painted it over. Inside is dark like you’re blind with only the cold metal to sit on and so crowded you are always touching someone. There is a smell of rust and old water and the walls are alive with something that likes to grow in the wet and dark, something that needs much less air than a man.

Most of us have only a liter of water because it is such a short trip. That is all I have too, but I didn’t forget that feeling I had yesterday morning when the truck stopped and we thought we were there and César said, “Dios, espero que sí.” That little prayer, maybe it’s his premonition, I don’t know, but after it I was careful with my water. The others are saying this also — Save your water. But now it’s too late. Some people finished their water already and the food they brought is no good — Mars bars and lollipops and chicharrones con salsa — I know it by the smell. We are like children in here. Locked in a dark room.