Rogers Writers’ Trust: Spotlight on Omar El Akkad

We asked the 2017 nominees: Do you consider yourself a politically engaged writer? How does that affect your work?

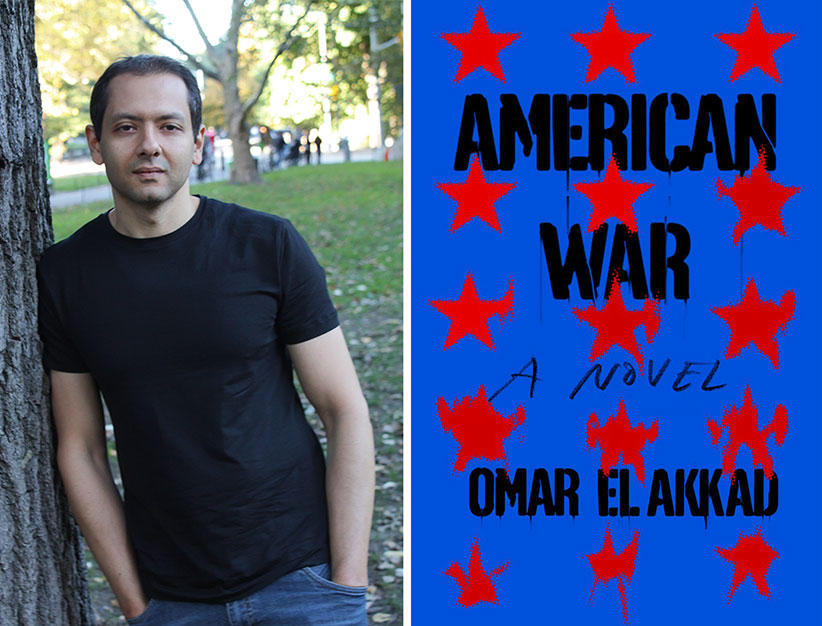

Omar El Akkad

Share

Omar El Akkad is nominated for the 2017 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for his novel American War. The winner will be announced at the Writers’ Trust Awards ceremony in Toronto on November 14. The winner of the newly enriched award receives $50,000. Each nominee receives $5,000. During the weeks leading up to the event, Maclean’s will publish an excerpt from each shortlisted writer, along with their answer to this one question: Do you consider yourself a politically engaged writer? How does that affect your work? Here is El Akkad’s response.

I’m a Muslim immigrant of Arab descent living in the West—my existence is political, and I had no say in the matter. I write what I feel is necessary, what I need to say. The extent to which my writing is deemed political may influence the way it is received or critiqued, but that’s someone else’s problem. Literature turns political when politics, not literature, oversteps its bounds. In those moments—and we are certainly living through one such moment right now—a writer has no choice but to become politically engaged. To do otherwise is a cop-out.

Excerpted from American War. Copyright © 2017 by Omar El Akkad. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House company. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

The sun broke through a pilgrimage of clouds and cast its unblinking eye upon the Mississippi Sea.

The coastal waters were brown and still. The sea’s mouth opened wide over ruined marshland, and every year grew wider, the water picking away at the silt and sand and clay, until the old riverside plantation and plastics factories and marine railways became unstable. Before the buildings slid into the water for good, they were stripped of their usable parts by the delta’s last holdout residents. The water swallowed the land. To the southeast, the once glorious city of New Orleans became a well within the walls of its levees. The baptismal rites of a new America.

A little girl, six years old, sat on the porch of her family’s home under a clapboard awning. She held a plastic container of honey, which was made in the shape of a bear. From the top of its head golden liquid slid out onto the cheap pine floorboard.

The girl poured the honey into the wood’s deep knots and watched the serpentine manner in which the liquid took to the contours of its new surroundings. This is her earliest memory, the moment she begins.

And this is how, in those moments when the bitterness subsides, I choose to remember her. A child.

I wish I had known her then, in those years when she was still unbroken.

“Sara Chestnut, what do you think you’re doing?” said the girl’s mother, standing behind her near the door of the shipping container in which the Chestnuts made their home. “What did I tell you about wasting what’s not yours to waste?”

“Sorry, Mama.”

“Did you work to buy that honey, hmm? No, I didn’t think you did. Go get your sister and get your butt to breakfast before your daddy leaves.”

“OK, Mama,” the girl said, handing back the half-empty container. She ducked past her mother who patted dirt from the seat of her fleur-de-lis dress.

Her name was Sara T. Chestnut but she called herself Sarat. The latter was born of a misunderstanding at the schoolhouse earlier that year. The new kindergarten teacher accidentally read the girls’ middle initial as the last letter of her first name—Sarat. To the little girl’s ears, the new name had a bite to it. Sara ended with an impotent exhale, a fading ahh that disappeared into the air. Sarat snapped shut like a bear trap. A few months later, the school shut down, most of the teachers and students forced northward by the encroaching war. But the name stuck.

Sarat.