The brief and tumultuous career of Bert Berns

Review of Here Comes the Night shows the painful side of rhythm and blues

Share

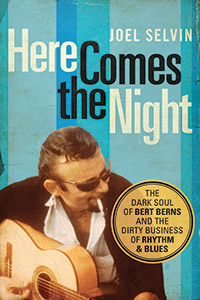

Review of HERE COMES THE NIGHT: THE DARK SOUL OF BERT BERNS AND THE DIRTY BUSINESS OF RHYTHM & BLUES

By Joel Selvin

Bert Berns had everything it takes to be a success in the record business: a songwriter’s instincts, an arranger’s ear, fingers on pulses in the U.S. and the U.K., and bravado. New to Atlantic Records as a staff producer in 1961, he told his boss, Jerry Wexler, that the anemic first recording Wexler and wunderkind Phil Spector had made of his song Twist and Shout, with the group the Top Notes, had “f–ked it up.” Soon, the likes of the Isley Brothers and the Beatles would prove him right.

Berns earned respect during a brief career that saw him craft soul-pop classics such as Piece of My Heart and Everybody Needs Somebody to Love, but he also made a lot of enemies with his brash business approach that increasingly relied on mobsters. Soon after he died of a heart attack in 1967, at age 38, he was forgotten; along with an off-Broadway musical to open in the summer, this book, by long-time San Francisco Chronicle rock writer Selvin, is part of an attempt to return him to the popular consciousness. It’s no hagiography though: Berns is revealed as one of the brilliantly unhinged characters who haunted Manhattan’s Brill Building in the 1960s, better able to guide his art than his personal life—faced with an ultimatum from his wife that it was either her or the dog, he chose the latter.

Selvin has such great fun telling tales about off-kilter, unscrupulous record-biz denizens that Berns himself is often lost in a sprawling, rambling narrative of behind-the-scenes pop music chicanery with more characters and skulduggery than Game of Thrones. Nonetheless, the book is both an informative history of a wild time in the music business and a compendium of acerbically delivered gossip—we read, for instance, about a young, drunk Van Morrison getting beaten up with his own acoustic guitar by a mob-connected record exec who “felt bad because it was a nice guitar.”

Berns comes across as likeable despite his heavy-handed approach. He loved the painful side of rhythm and blues: in the studio, he would dredge up near-histrionic emotion from his artists, and Selvin believes he was expressing his own despair. Diagnosed with rheumatic fever at 14, Berns raced through life knowing he had a death sentence and gave everything to a business that ultimately let his name slide into oblivion. His story is worthy of his songs.